A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 is a series of eight satirical paintings by the English artist William Hogarth (1697–1764), an artist renowned for his innovative paintings and engravings depicting what he styled as ‘modern moral subjects’.1 The series tells the story of Tom Rakewell (the Rake), a man who inherits a fortune from his city merchant father only to fritter it away on an extravagant lifestyle which ultimately leads to his downfall. The series (fig.1a–h) is known to have remained in Hogarth’s possession until 1745 when he sold them by private auction, alongside A Harlot’s Progress 1731, to William Beckford the Elder, politician and owner of plantations in Jamaica worked by large numbers of enslaved people.2 A Rake’s Progress stayed in the Beckford collection until 1802 when it was sold to the architect John Soane.3 The series has since remained in the collection of Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Hogarth first advertised the forthcoming prints of A Rake’s Progress in 1733.4 The paintings were made, in part, as preparatory works for engravings, to be sold by subscription as a series of eight prints. They were also, however, significant works of art in their own right, building Hogarth’s reputation as a pioneering painter of modern narratives. The development of A Rake’s Progress from painting to print marks an important period in the artist’s career. During this time not only did he consolidate his role within the British art scene but, significantly, he also embarked upon his petition to parliament to prevent plagiarism of his (and others’) work, culminating in the Copyright Act of June 1735, also known as Hogarth’s Act.

Fig.2

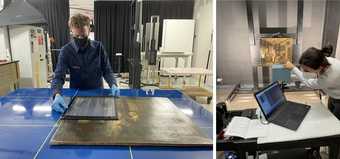

Left: Joe Humphrys preparing William Hogarth’s V The Marriage from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) for X-radiography in the Photography department. Right: Gabriella Macaro using Tate’s Apollo infrared reflectography camera in the Tate Paintings Conservation department

Photo © Tate

The loan of the series by Sir John Soane’s Museum to the Hogarth and Europe exhibition at Tate Britain (3 November 2021 – 20 March 2022) gave us an opportunity to research the series, alongside several other Hogarth works in Tate’s own collection, across multiple departments at Tate: Paintings Conservation, Conservation Science, Curatorial, and Photography. It provided a unique occasion for Tate and experts from the Soane to come together to examine the paintings unframed in our Paintings Conservation studio and to see what technical analysis might reveal about them. Our close examination of the multiple compositional changes within the eight paintings that comprise A Rake’s Progress, including examination with infrared reflectography (IRR) and X-radiography to see through the sequence of paint layers (fig.2), has shed new light on the relationship between his paintings and prints and expanded our understanding of Hogarth’s personal struggle with piracy and copyright.5

Development of Hogarth’s compositions on the canvas

Fig.3

Photomicrograph (x0.8 magnification) detail showing red paint from underlying composition, visible between the drying cracks of the uppermost paint layers of William Hogarth’s VIII The Madhouse from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum)

Photo © Tate

Hogarth is known to have worked out his compositions as he painted, altering figures and objects, adding or omitting details and characters as he went.6 For A Rake’s Progress, our technical examinations have shown that Hogarth developed his ideas directly onto the canvas with a brush, rather than following a predetermined sketch.7 This method of working is sometimes apparent to the unaided eye, and the presence of a fine network of drying (shrinkage) cracks across all eight paintings frequently gives us clues as to where Hogarth altered or reworked his designs. In VIII The Madhouse, for example, we saw glimpses of an underlying red paint between the drying cracks in the uppermost paint layers;8 the composition below, however, remained hidden without the use of additional analytical techniques (fig.3).

Fig.4

Detail of William Hogarth’s II The Levée from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) in visible light (left) and infrared reflectogram (right). The infrared reflectogram shows alterations to the position of the fencer’s arm and leg.

Photo © Tate

Through technical examination and imaging to reveal what lies beneath the picture surface, we were able to clearly identify some of the changes made by Hogarth to the position of figures and objects before settling on the final composition. In all eight paintings, we observed small changes to the position of limbs, hands and fingers, in some cases several times, to subtly alter a figure’s gesture (fig.4).

Fig.5

Detail of William Hogarth’s I The Heir from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) in visible light (left) and infrared reflectogram (right). The infrared reflectogram shows the fireplace was painted in full before adding the old woman lighting the fire

Photo © Tate

In some instances, Hogarth painted objects and figures in their entirety before deciding to add an additional element. The infrared image of I The Heir aids our visual observation, showing that Hogarth painted the fireplace in full before adding the old woman lighting the fire (fig.5). This supports Hogarth’s announcement on 2 November 1734 that the prints were delayed because he found it ‘necessary to introduce several additional Characters in his Paintings of the Rake’s Progress’.9 As discussed below, however, Hogarth’s decision to delay was also undoubtedly influenced by the imminent passing of the Copyright Act.

Alterations to VIII The Madhouse

Fig.7

Detail of William Hogarth’s VIII The Madhouse from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5: in visible light (left); in X-ray (centre); and of the engraving on paper (Tate), inverted (right). The X-ray shows that Tom’s original position in the painting of VIII The Madhouse matched that of the position shown in the print.

Photo © Tate

We found significant compositional changes in VIII The Madhouse (figs.6a–b) – an X-ray of the painting showed that Hogarth initially painted the figures of the protagonist, Tom Rakewell, and the ever-devoted Sarah Young much closer in position and sentiment to their appearance in the print (fig.7).10 This finding led us to believe that Hogarth returned to the painting and changed the central figure after the engravings were made. This contrasts with the sequence of painting and print for the other seven works, where key features of the final composition in the painting are copied in the corresponding print, and compositional changes in the subsequent print states are not reflected in changes to the paintings.

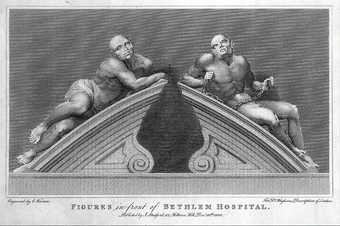

Fig.8

Print depicting Caius Gabriel Cibber’s statues Melancholy and Raving Madness both 1676, which once crowned the gates at Bethlem psychiatric hospital

Wellcome Library, London

Tom’s pose, lying prostrate in the foreground with chains at his wrists and ankles, is thought to be modelled upon sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber’s life-size statues of Melancholy and Raving Madness, both 1676 (fig.8), which crowned the gates of Bethlehem (Bethlem) Royal Hospital for psychiatric patients, known as ‘Bedlam’, where this painting is set.11 These statues were well known landmarks in eighteenth-century London, and to Hogarth’s contemporaries the two figures were recognisable as representations of the two most common diagnoses that someone with mental illness could receive at the time.12

In the first rendering of the painting and in subsequent engravings, Hogarth appears to show Tom in a position reminiscent of Raving Madness: his body is taut, his arm is raised, both his knees are bent and he wears a pained expression. The later shift in Tom’s position suggests that Hogarth had a change of mind, instead opting for the more classical pose with echoes of Cibber’s Melancholy.13 Since the series remained in Hogarth’s possession until 1745, this alteration could have been made several years later but there is no conclusive evidence for when and why this change was made.14

Fig.9

Details of William Hogarth’s VIII The Madhouse from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) in visible light (left) and infrared reflectogram (right). The infrared reflectogram shows three figures in the background from a previous iteration of Hogarth’s composition

Photo © Tate

Another significant change to VIII The Madhouse is the presence of three ghostly figures in the background, subsequently painted over by Hogarth and now just visible to the unaided eye. These are not present in the prints so it is likely that they were altered at an early stage of the painting’s development. X-radiography and IRR have allowed us to speculate further as to Hogarth’s intention with these figures (fig.9). On the left there appears to be a man wearing a red jacket and a wig, explaining the red paint that was initially spotted through the drying cracks in the upper paint layers. This figure is possibly an earlier iteration of the prison warden or keeper now seen to the side of Sarah and behind Tom.15

Further in the background still, the central hidden figure is a man standing in profile with what appears to be a large beer tankard upside down on his head.16 The hidden man also holds what seems to be a staff, close in style to the one held by the inmate in cell fifty-five. The technical images have reinforced the suggestion by Joanna Tinworth, Curator (Collections) at Sir John Soane’s Museum, that this figure might initially have been the ‘regal inmate’ in cell 55.17 The hidden figure to the right appears to have a head of thick curly hair and wears what could be a laurel wreath.18 Perhaps this figure was an early interpretation of another inmate who imagined himself to be a Roman emperor.

Alterations to IV The Arrest

IV The Arrest is undoubtedly the scene that Hogarth reworked the most, both in the painting and the engraving. In this scene, Tom Rakewell is shown being arrested on his way to visit the Royal Court at St James’s Palace. The scene is set on 1 March, which is St David’s Day, as represented by the two men, presumed to be Welsh, wearing leeks in their hats in the final painting. In the background we see the reception at St James’s Palace for Queen Caroline’s birthday.19

Fig.10

Detail showing reddish-brown paint beneath the blue sky of William Hogarth’s IV The Arrest from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum)

Photo © Tate

Fig.11

Detail of William Hogarth’s IV The Arrest from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) in visible light (left) and infrared reflectogram (right). The infrared reflectogram shows a figure of a life-sized, seated effigy suspended from a post underneath the final composition

Photo © Tate

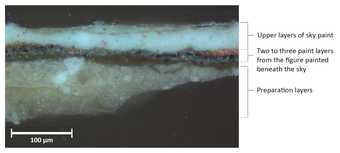

Fig.12

Paint cross-section from the blue sky of William Hogarth’s IV The Arrest from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum), showing paint layers of the figure beneath the sky

Photo © Tate

Looking with the unaided eye, we could already speculate that there were a significant number of alterations underneath this painting, suggested by clues such as a warm reddish-brown layer visible through the light blue brushstrokes of the sky (fig.10). The infrared image confirmed a number of changes, including a remarkable figure of a life-sized, seated effigy suspended from a post (fig.11). We took a minute paint sample from this area, the cross-section of which confirmed the existence of this figure beneath the paint layers of the sky (fig.12). The outline of a leek in his hat in the infrared image suggests the effigy might also be intended as a Welshman, a sight recorded on St David’s Day by the diarist Samuel Pepys.20

Fig.13a

William Hogarth’s IV The Arrest from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) in visible light

Photo © Tate

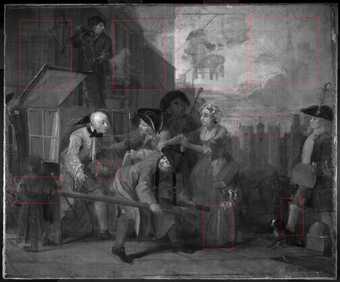

Fig.13b

Infrared reflectogram of William Hogarth’s IV The Arrest from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum). Red boxes show areas where the composition can be seen to have changed.

Photo © Tate

The infrared image additionally shows a shop sign protruding from the left-hand building (fig.13b) and that the building itself has been altered, originally having a single façade with two larger windows facing the viewer. To the right, in the sky, additional buildings were painted in the background, including a tall church spire. The difference in perspective between the façade to the left and the buildings to the right suggests that Hogarth tried out several iterations before finalising his composition. It is hoped that with the use of additional analytical imaging techniques (such as macro X-ray fluorescence scanning (MA-XRF)), which was not possible in the remit of this technical study, it might be possible to distinguish between the different stages in Hogarth’s development of the composition.21

Piracy and the Copyright Act of 1735

While we do not know why Hogarth decided to paint over the suspended figure in IV The Arrest, the months leading up to publication of the prints for A Rake’s Progress on 25 June 1735 offer an interesting context for some of the compositional changes we observed.

Hogarth’s first advertisement of a subscription for the eight prints of A Rake’s Progress on 9 October 1733, indicated that the paintings were complete enough by this time for prospective subscribers to view them.22 Yet the paintings were not announced as finished until 2 November 1734:

having found it necessary to introduce several additional Characters in his [Hogarth’s] Paintings of the Rake’s Progress, he could not get the Prints ready to deliver to his Subscribers at Michaelmas [Sept.29] last (as he proposed.) But all the Pictures being now entirely finished, may be seen at his House, the Golden-Head in Leicester-Fields, where Subscriptions are taken.23

Having engraved and published his own prints for the highly successful earlier series, A Harlot’s Progress in 1732, Hogarth was well aware of the financial advantages of eliminating the print-seller and publisher as middlemen.24 However, he had also suffered significant loss of income and control over quality due to the prolific plagiarism of his prints.25 In response, by 1734, Hogarth had begun ‘An Act for the encouragement of the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints, by vesting the properties thereof in the inventors and engravers’, petitioning parliament to support legal ownership and profit for an artists’ own work.26 Although Hogarth may have initially delayed the print publication due to compositional changes to his paintings, the several months of delays that followed were likely an attempt to negate the piracy, yet again, of his work by copyists.27

In a final delay announced on 10 May 1735, Hogarth is explicit about the reasons for postponing the print distribution to subscribers:

N.B. Mr. Hogarth was, and is oblig’d to defer the Publication and Delivery of the abovesaid Prints till the 25th June next, in order to secure his Property, pursuant to an Act lately passed both Houses of Parliament, now awaiting for the Royal Assent, to secure all new invented Prints that shall be published after the 24th of June next, from being copied without Consent of the Proprietor, and thereby preventing a scandalous and unjust Custom (hitherto practiced with Impunity) of making and vending base Copies of original Prints, to the manifest Discouragement of the Arts of Paintings and Engraving.28

Hogarth finally released the prints for A Rake’s Progress on 25 June 1735, as the Copyright Act came into force.29

Despite his best efforts, A Rake’s Progress was still copied by plagiarists. An early piracy, The Progress of a Rake, Exemplified in the Adventures of Ramble Gripe, Esq; Son and Heir of Sir Positive Gripe, was even advertised in June 1735 – before Hogarth’s own prints were published.30 Hogarth described the new and ingenious methods plagiarists used to get access to his designs in an advertisement on 3 June 1735 in the London Evening Post:

Several Printsellers … have resolv’d nothwithstanding to continue their injurious Proceedings at least till that Time, and have in a clandestine Manner, procured mean and necessitous Persons to come to Mr. William Hogarth’s house, under the pretence of seeing his RAKE’S PROGRESS [as prospective subscribers], in order to pyrate the same, and publish base Prints thereof before the Act commences, and even before Mr. Hogarth himself can publish the true ones.31

Fig.14

After William Hogarth

The Progress of a Rake, Exemplified in the Adventures of Ramble Gripe Esq. Son of Sr Positive Gripe: Going to Court He Is Arrested at St. James’s Gate 1735, showing the effigy on the left-hand side

engraving on paper

343 mm x 384 mm

British Museum

© The Trustees of the British Museum

This early piracy provides evidence that the painting of IV The Arrest was almost certainly seen at Hogarth’s home in its earlier iteration (with the suspended figure), as it shows a similar effigy of a presumed Welshman in the background, perched on a post with leek in hat (fig.14).32 This feature of Hogarth’s initial composition would have been a striking and memorable image for the clandestine ‘Persons’ to mentally note and report back to a pirate engraver and, moreover, suggests that Hogarth continued to significantly adjust his paintings while viewings and print subscriptions were underway.

Fig.15

After William Hogarth

The Progress of a Rake, Exemplified in the Adventures of Ramble Gripe Esq. Son of Sr Positive Gripe: He Comes Into the Possession of His Father’s Estate 1735

engraving on paper

270 x 326 mm

British Museum

© Trustees of the British Museum

Although there are many differences between the early piracies and Hogarth’s own prints, as might be expected from a picture retold by memory, in an early plagiarised print of I The Heir (fig.15) the old woman by the fire is omitted, which may suggest that she too was a later alteration made after the plagiarist had viewed the painting.33

Without further technical analysis or documentary evidence, the chronology of Hogarth’s painting process remains speculative. However, it is interesting to consider that although viewings of the paintings at the Golden-Head were advertised multiple times from 9 October 1733 until subscriptions closed on 23 June 1735, pirate printmakers may have adopted this method of spying only after the petition for the Copyright Act was submitted to parliament in early February 1735.34 It is possible then, that Hogarth reworked I The Heir, IV The Arrest and VIII The Madhouse, and maybe others, even after his announcement that they were ‘entirely finished’ on 2 November 1734.

Conclusions

This project has been a unique opportunity for the team at Tate to delve deeper into the materials and techniques of Hogarth’s famous series. Hours of discussion and close scrutiny of the works, alongside experts from the Sir John Soane’s Museum, has been both a privilege and a fascinating journey of discovery. IRR and X-ray imaging have revealed multiple minor alterations made by Hogarth throughout the painting process as he worked out his narrative directly onto the canvas. Larger scale changes to the compositions, notably in VIII The Madhouse and IV The Arrest, have provided new insight into the development of these works from paintings to engravings and prints.

A full structural and aesthetic conservation treatment of these significant works by Hogarth is planned, and it is hoped that treatments such as removal of the aged varnish layers, as well as further collaborative technical analysis, will continue to add to our understanding of this important series of paintings.