A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 is a series of eight satirical paintings by the English artist William Hogarth (1697–1764), an artist renowned for his innovative paintings and engravings depicting what he styled as ‘modern moral subjects’.1 The series tells the story of Tom Rakewell (the Rake), a man who inherits a fortune from his city merchant father only to fritter it away on an extravagant lifestyle which ultimately leads to his downfall (fig.1a–h).

Fig.2

From left to right: Amy Griffin, Joyce Townsend and Alice Insley examining William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) in the Paintings Conservation Studio at Tate Britain

Photo © Tate

The loan of the series by Sir John Soane’s Museum to the Hogarth and Europe exhibition at Tate Britain (3 November 2021 – 20 March 2022) gave us an opportunity to research the series, alongside several other Hogarth works in Tate’s own collection, across multiple departments at Tate: Paintings Conservation, Conservation Science, Curatorial, and Photography. It provided a unique occasion for Tate and the Soane to come together to examine the paintings unframed in our Paintings Conservation studio (fig.2) and to see what technical analysis might reveal about them. Discussions in front of the paintings were enriched by recent curatorial research carried out at the Soane for their updated online catalogue entries.2

Hogarth is known to have had little formal training as a painter, being initially apprenticed to a silver engraver from 1713.3 From 1720 he turned his hand first to printmaking and later to painting.4 He attended the academy run by Louis Cheron and John Vanderbank in St Martin’s Lane, and later James Thornhill’s academy in Covent Garden, before initiating his own academy in St Martin’s Lane in 1735.5 Hogarth’s involvement in these early academies would have placed him in close contact with current theories of painting and exposed him to the working methods of other contemporary artists in England and Europe. This feature outlines the results of our technical analyses in terms of Hogarth’s technique, painting practices and selection of materials, and allows us to consider how typical his practice was for the time.

Supports

Fig.3

William Hogarth

William Hogarth c.1757–8

oil on canvas

451 x 425 mm

National Portrait Gallery, London

Like most eighteenth-century painters, Hogarth favoured canvas as the primary support for his paintings. He probably painted A Rake’s Progress at an easel with his canvases already attached to a wooden stretcher or strainer, the setup shown in his c.1757 self-portrait (fig.3). The wooden stretchers currently present on all eight paintings in the Rake series are not, however, original and are likely to have been introduced when the paintings were lined in an early conservation treatment.6 When a painting is lined it is attached, with glue, to a new piece of canvas to provide structural stability. Looking closely at the edges of the paintings, we could see that the original fold-over edges of Hogarth’s canvases were partially trimmed during this historic lining process, meaning we can only estimate the exact size of the original canvases.7 However, remnants of the original tack holes confirmed that the paintings have not been significantly reduced in size, and that Hogarth may have used a standard ‘three-quarter size’ canvas which would have been available ready-made from artists’ suppliers in the eighteenth century.8

Hogarth’s original linen canvases in seven of the paintings in A Rake’s Progress are of a fine plain weave, whereas VI The Gaming House is instead painted on a twill weave canvas.9 Although twill canvas was used by other painters working in England at the time, it appears an unusual choice for Hogarth, who principally used fine linen with a plain weave.10

Grounds

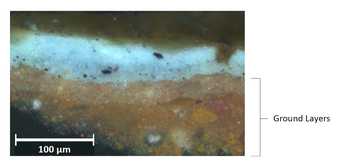

Fig.4

Paint cross-section from the crimson curtain in William Hogarth’s III The Orgy from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum), showing the double ground layer

Photo © Tate

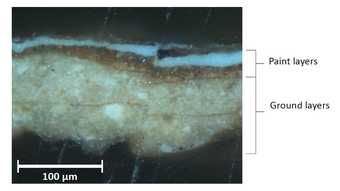

Fig.5

Details showing linear striations in the ground layers visible through the paint layers of William Hogarth’s I The Heir from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum)

Photo © Tate

Before the paint is applied, canvases are typically prepared with what is known as a ground (or preparatory layer), which varies in colour, thickness and absorbency. The function of these grounds is to reduce the absorbency of the cloth and provide a more uniform surface on which to apply paint. Preparatory layers observed on historic paintings vary hugely in layer structure and composition, but the most commonly observed construction in mid-eighteenth-century British painting is two layers of pale-coloured ground, often separated by a thin layer of glue size, a dilute animal glue.11 We took and examined minute paint samples from A Rake’s Progress, set them in synthetic resin, and ground and polished them to obtain a cross-section through all the layers. By examining these cross-sections using a microscope we were able to see for the first time that the grounds of seven of the eight canvases do indeed consist of two layers of a pale greyish-buff colour, separated by a glue size layer (fig.4).12 By looking at the paintings’ surfaces under the microscope we could also see that, in these seven works, the upper layer of ground was slightly textured with uniform linear striations running across the surface, most likely resulting from the tool used to apply the ground (fig.5).13

Senior Conservation Scientist Joyce Townsend used microscopy and SEM-EDX (scanning electron microscopy- energy dispersive X-ray analysis) to carry out pigment analysis of the double ground layers, which showed that the layers are largely made up of lead white and chalk (calcium carbonate) with additions of pipeclay and lightly tinted with small amounts of brown earth and bone black pigment. The uniformity of the ground preparation over the majority of the series suggests that Hogarth might have purchased his canvases, or ‘cloths’ as they were known, ready-primed from a colour merchant.14 Painters in the mid-eighteenth century were producing works at high speed in a competitive art market, so making use of such prepared canvases was a favourable alternative to the laborious practice of stretching and priming canvases in their own studios.

Fig.6

Paint cross-section from the background of William Hogarth’s VI The Gaming House from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum), showing the warmer-coloured ground

Photo © Tate

In VI The Gaming House, the ground has a warmer hue and a smoother surface (fig.6). The layers of the ground again consist predominantly of lead white and chalk but, compared to the other seven works in the series, contain higher proportions of lead white and pipeclay, and are tinted with particles of a reddish-orange pigment in addition to the brown and black pigments present in the others.

Fig.7

Paint cross-section from the sky in William Hogarth’s O the Roast Beef of Old England ('The Gate of Calais’) 1748, showing the reddish-brown ground

Photo © Tate

To contextualise the ground layers found within the eight paintings of A Rake’s Progress, we examined and analysed a number of paint samples from other paintings by Hogarth in Tate’s collection. Four of these – A Scene from ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ VI 1731, James Quin, Actor c.1739, The Staymaker c.1745 and The Dance c.1745 – have a pale greyish-buff ground similar to that seen in A Rake’s Progress. Moreover, all four grounds display the same linear striations. We noted a difference in the case of O the Roast Beef of Old England (‘The Gate of Calais’), painted later in 1748. This painting has a reddish-brown ground (fig.7), darker and redder than that of VI The Gaming House.15 We cannot say, at this stage, why VI The Gaming House was the only painting of the series where Hogarth used different materials for the canvas and ground, but it is still interesting to note that he experimented with warmer, though still pale grounds, at this earlier stage in his career.

Pigments and paint medium

Fig.8

Paint cross-section from the reworked sky of William Hogarth’s IV The Arrest from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) showing the thickness of the ground and paint layers

Photo © Tate

From the cross-sections of paint samples from all eight paintings, we were able to see that Hogarth applied his paint in a simple layer structure, with the paint layers consistently thinner than the ground layers (fig.8). Throughout the series, the cross-sections also included multiple layers of non-original varnish, as might be expected for paintings of this age which are likely to have been cleaned and re-varnished numerous times.

Microscopy at magnifications between x50 and x320, in combination with elemental analysis (using SEM-EDX), has revealed the pigments Hogarth employed in the making of A Rake’s Progress.16 He mixed most of his colours in an oil medium with two or three pigments from the following range: bright red vermilion, red ochre, a dark crimson red lake, yellow ochre, massicot (a lead oxide) for the brighter yellows, blue bice (a synthetic copper carbonate), brown earth, Vandyke brown and black.17 For greens he mixed yellow ochre and Prussian blue, the latter being his most regularly used blue pigment and of an unusual light tone.18 Coarse and finely ground bone black were identified in a great number of the light-toned fabrics, as well as in the darker passages of paint. Lead white was also identified throughout the paint layers, used to lighten colours. We found that Hogarth used a relatively traditional palette of pigments for A Rake’s Progress, and all the pigments that have been identified were well established at the time the series was painted.

Fig.9

A pig’s bladder used to store ready-mixed paint prior to the nineteenth-century invention of the collapsible metal paint tube

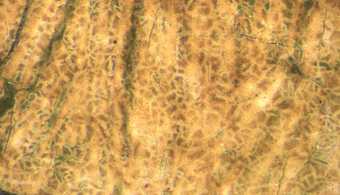

Fig.10

Photomicrograph of Tom’s pink coat in William Hogarth’s II The Levée from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum), showing areas of microcissing beneath the aged yellowing varnish

Photo © Tate

It is likely that Hogarth bought his paints ready for use, supplied already ground with oil in small bladder skins (fig.9) as single-coloured pigments with a limited lifetime once opened. He could then add more medium and modifiers to the paint on the palette to make bodied paint useful for impasto, or a lead-based siccative (drier) to accelerate the drying time of the paint and shorten the wait before a painting could leave the studio. Rica Jones, expert in sixteenth-eighteenth century British painting techniques, has noted that ‘the exigencies of making a living out of oil painting in a northerly climate [which makes paint take longer to dry] amidst fierce competition and fickle public taste’, may have increased contemporary demand for fast drying paint.19 Indeed, when we observed the paint surfaces of A Rake’s Progress with a microscope, we saw a very fine crack pattern known as microcissing, caused by the extensive use of lead-based siccatives (driers) in the binding medium (fig.10).20 We found that this phenomenon, common to British paintings of this period, is notably prominent in dark and bright yellow colours in A Rake’s Progress, as well as in thicker paint applications and depictions of textured surfaces.21

Technique

Fig.11

Detail of the fastenings on Tom’s pink coat in II The Levée from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum)

Photo © Tate

Fig.12

Details of William Hogarth’s V The Marriage (left) and VII The Prison (right) from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum), showing the brushwork used for lace and linen borders

Photo © Tate

Fig.13

Detail of the central sex worker’s bodice in William Hogarth’s III The Orgy from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum), showing the artist’s technique for sketching in shadows

Photo © Tate

Fig.14

Details of William Hogarth’s V The Marriage (left) and II The Levée (right) from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum), showing Hogarth's painting technique for figures in the background

Photo © Tate

Fig.15

Details of William Hogarth’s I The Heir (left) and II The Levée (right) from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum), showing brushwork used for Tom Rakewell’s face

Photo © Tate

Access to the paintings in the Conservation studio has allowed us to closely examine Hogarth’s brushstrokes and discuss his technique with Helen Dorey and Joanna Tinworth, Deputy Director and Curator (Collections) at Sir John Soane’s Museum. Hogarth’s paint application gives the impression of a swift and lively technique, in a few strokes conveying both form and texture, as in the fastening of Tom’s coat in II The Levée (fig.11), or the continuous zig-zag brushstrokes used to form lace and white linen borders (fig.12). In many cases a single stroke is used to sketch in a high or low light, as can be seen in shadows of the bodice of the central sex worker in III The Orgy (fig.13). Figures in the background are consistently depicted using simplified brushstrokes with a range of three or so colours (fig.14). For figures of central importance, the paint is applied in an opaque manner with fine, blended brushwork following the contours of the face or hands (fig.15).

Our technical examination of A Rake’s Progress shows no evidence of underdrawing in a dry medium, supporting Hogarth’s description in his unfinished Autobiographical Notes of his preferred method of working from memory:22

the retaining in my mind’s Eye without drawing upon the spot whatever I wanted [to] imitate & soon found by experience this was the readiest and least laborious way for by this means my studies and my Pleasures went hand in hand & the most striking incidents that presented themselves to my view ever made the strongest impressions on my memory.23

Our technical examinations suggest that Hogarth loosely worked out his compositions on the primed canvas using dilute washes of paint which he then worked up in thicker more opaque paint. It also shows that throughout the process of painting, Hogarth made alterations to his composition, sometimes resulting in a narrative shift. This working method is a subject we discuss in ‘The Development of Hogarth’s series, A Rake’s Progress: From Paintings to Prints’.

Conclusions

This project has offered a unique opportunity for the team at Tate to delve deeper into the materials of Hogarth’s famous series. Hours of discussion and close scrutiny of the works, alongside experts from Sir John Soane’s Museum, has been both a privilege and a fascinating journey of discovery.

Previous technical studies of Hogarth’s paintings have shown that he used grounds, pigments and oil binders considered typical in eighteenth-century Britain.24 A survey of new and past analysis undertaken on Hogarth’s paintings at Tate shows that his materials remained broadly consistent throughout the twenty-eight years represented in the collection (1731–1759), with a few exceptions in his use of canvas and preparatory layers. This ongoing collaborative research has shown that the same can be said of the materials used in A Rake’s Progress, with interesting differences noted in VI The Gaming House, that raise questions for further study.

A lack of formal training for painters in Britain in the eighteenth century has been noted by Rica Jones as being the catalyst for a proliferation of individual techniques among painters of the period.25 In this context, we can see Hogarth’s fluid development of his compositions directly on the canvas as characteristic of, and integral to, the painter’s own working method. Throughout A Rake’s Progress and other paintings by Hogarth in Tate’s collection, there are abundant instances of his re-working.26

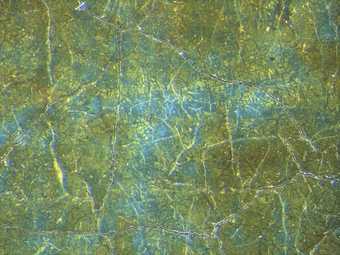

Fig.16

Photomicrograph of William Hogarth’s III The Orgy from A Rake’s Progress c.1733–5 (Sir John Soane’s Museum) showing blue paint of woman’s dress through gaps in the aged and yellowed varnish

Photo © Tate

A full structural and aesthetic conservation treatment of these significant works by Hogarth is planned, and it is hoped that treatment, such as the removal of the aged varnish layers (fig.16), as well as further collaborative technical analysis, will continue to add to our understanding of this important series of paintings.