Sir Joshua Reynolds

Three Ladies Adorning a Term of Hymen

(1773)

Tate

The term ‘history painting’ was introduced by the French Royal Academy in the seventeenth century. It was seen as the most important type (or ‘genre’), of painting above portraiture, the depiction of scenes from daily life (called genre painting), landscape and still life painting. (See the glossary page for genres to find out more).

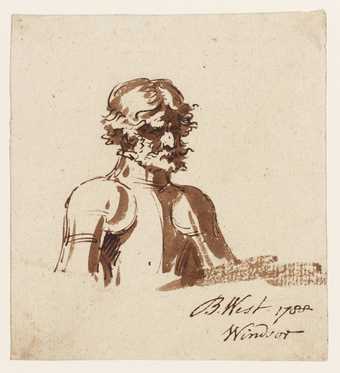

Although initially used to describe paintings with subjects drawn from ancient Greek and Roman (classical) history, classical mythology, and the Bible; towards the end of the eighteenth century history painting included modern historical subjects such as the battle scenes painted by artists Benjamin West and John Singleton Copley.

The style considered appropriate to use for history painting was classical and idealised – known as the ‘grand style’ – and the result was known overall as High Art.

John Singleton Copley

The Death of Major Peirson, 6 January 1781

(1783)

Tate

Philip Wilson Steer

What of the War?

(c.1881)

Tate

The role of the Empire in history painting

During the first half of the nineteenth century history painting was one of the few ways that the British public could experience its overseas Empire. In this context, history painting became a form of documentation. Artists such as Benjamin West and Henry Nelson O’Neil became more interested in painting scenes of recent and contemporary history, depicting people in modern dress rather than the ‘timeless attire’ as seen in traditional history painting.

The 1850s saw a shift in interest towards more human and intimate subject matter rather than a rendition of picturesque literary or grand historical themes. Battle scenes from the military sub-genre of history painting received criticism because they could not be relied upon to be accurate, and few battle scene paintings were exhibited at the Royal Academy. Philip Wilson Steer’s What of the War? was however exhibited there, suggesting that the private responses of civilians were perhaps a more honest testimony to the loss of life provoked by overseas conflict (in this case the Sudan war of 1881).

The role of history painting was to plummet even further in the twentieth century, disappearing almost entirely from art circles following the breakup of empire after the Second World War.