In Tate Britain

- Artist

- Damien Hirst born 1965

- Medium

- Glass, stainless steel, perspex, acrylic paint, lamb and formaldehyde solution

- Dimensions

- Displayed: 960 × 1490 × 510 mm

- Collection

- ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

- Acquisition

- ARTIST ROOMS Acquired jointly with the National Galleries of Scotland through The d'Offay Donation with assistance from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and the Art Fund 2008

- Reference

- AR00499

Summary

Away from the Flock is a floor-based sculpture consisting of a glass-walled tank filled with formaldehyde solution in which a dead sheep is fixed so that it appears to be alive and caught in movement. Thick white frames surround and support the tank, setting in brilliant relief the transparent turquoise of the solution in which the sheep is immersed. Away from the Flock is unusual for a Hirst sculpture in that it exists in three versions, all created the same year, of which ARTIST ROOM’s is the third. The principal difference between the three versions (reproduced together Hirst and Burn, pp.84–5) is that the sheep in the first version has an entirely black head and its forelegs are raised further off the floor of the tank, so that it appears to be arrested mid-jump. The sheep in versions two and three are more similar in appearance and in pose; ARTIST ROOM’s sheep has less black on its head and a pinker tinge in the rest of its wool than the others.

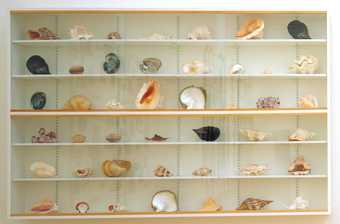

Away from the Flock is one of a group of sculptures collectively entitled Natural History, that Hirst initiated in 1991 with what was to become one of his most famous works, a tiger shark floating in a giant formaldehyde-filled tank, entitled The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Somebody Living (reproduced Damien Hirst, pp.120–1). In the same year the artist filled two sets of shelves with fish in solution in individual Perspex boxes and titled the two separate works Isolated Elements Swimming in the Same Direction for the Purpose of Understanding followed by the bracketed words ‘left’ and ‘right’ indicating the ways the fish are heading (reproduced Damien Hirst, pp.114–15). He also made his first works with ungulate carcasses in liquid: Stimulants (and the way they affect the mind and body) (reproduced Damien Hirst, p.125), consisting of two cuboid tanks each containing a skinned sheep’s head and Out of Sight. Out of Mind (reproduced Stuart Morgan, Damien Hirst: No Sense of Absolute Corruption, exhibition catalogue, Gagosian Gallery, New York 1996, p.37), two individually encased skinned cows’ heads. In 1993 he created Mother and Child Divided (T12751), using the carcasses of cow and a calf, sliced in half and mounted in four separate tanks. This was his first use of bissected animals; he created Away from the Flock Divided (private collection, New York) in 1995.

The heavy frames of Hirst’s tanks have been a signature structure since he created his first steel-framed vitrine in 1990, A Thousand Years 1990 (reproduced Hirst pp.28–33), in which a pair of interlinked glass cells hosts a colony of flies living in a rotting cow’s head and dying on an Insect-O-Cutor. Like A Thousand Years, many of Hirst’s Natural History works – most notably those in which animals are skinned or sliced – combine the pure clean lines of classic Minimalist sculpture, with the uncomfortably eviscerated flesh of a portrait by the painter Francis Bacon (1909–92). Bacon saw and praised A Thousand Years not long before he died in 1992. Hirst has frequently cited Bacon as an early influence (Hirst and Burn, pp.68–9), making a sculptural homage to Bacon’s many triptychs of his lover George Dyer in a work entitled The Tranquillity of Solitude (For George Dyer) 2006, in which skinned sheeps’ carcasses take the place of Dyer, sitting on a toilet or leaning over a basin, each individually immersed in a formaldehyde-filled vitrine.

The heavy industrial aesthetic of the Hirst’s tanks and vitrines references the sculptural forms of such American Minimalists as Donald Judd (1928–94) and Carl André (born 1935). Placing objects in solution in tanks, Hirst follows the precedent of American Pop artist Jeff Koons (born 1955), whose Total Equilibrium Tanks created in 1985 fetishised professional baseballs and art objects at the same time by suspending the balls in solution in glass vitrines on black steel stands (see T06991). Hirst has commented that the vitrines, ‘first came from a fear of everything in life being so fragile’ and wanting ‘to make a sculpture where the fragility was encased. Where it exists in its own space. The sculpture is spatially contained.’ (Quoted in Button, p.114.) The white frames that surround the formaldehyde tanks are particularly dominating visually because of their width, and now function as something of an artist’s logo. Hirst has explained that he is attracted to formaldehyde ‘because it is dangerous and it burns your skin. If you breathe it in it chokes you and it looks like water. I associate it with memory.’ (Hirst, p.298.) He has also commented that he uses it not for its preservative qualities, but ‘to communicate an idea’ (quoted in Adrian Dannatt, ‘Damien Hirst: Life’s like this, then it stops’, Flash Art, no.169, March–April 1993, p.61). Central to this is the futility of preservation in the face of death – that whatever we do to protect bodies against entropy, inevitably, eventually they will disintegrate and die.

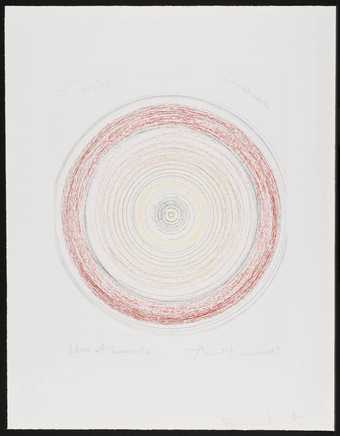

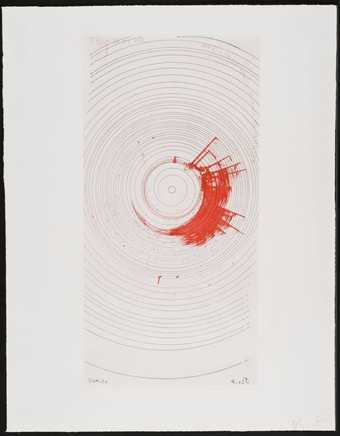

With the Natural History series, Hirst said that he, ‘just wanted to do a zoo that worked ... because I hate the zoo, and I just thought it would be great to do a zoo of dead animals, instead of having living animals pacing about in misery ... I never thought of [the works] ... as violent. I always thought of them as sad. There is a kind of tragedy with all those pieces.’ (Quoted in Damien Hirst, pp.122 and 134.) Although Hirst’s ‘zoo’ includes a shark, the other creatures he has used in this series are mainly domestic ungulates (sheep and cattle) as he seeks to refamiliarize people with the real source of butcher’s meat. He has commented: ‘It’s the banal animal that gives it the emotion. You wouldn’t feel the same about a tiger.’ (Quoted in Morgan, p.18.) His oeuvre is pivoted on a binary axis of death and depression versus life and joy, articulated through such material oppositions as flies versus butterflies and black versus white (see AR00045). The darkness or sadness in the Natural History series may be pitched against the happiness of the spot and spin paintings (see AR00498 and P13034–P13056).

Questioned about the title of the work, Hirst responded:

Away from the Flock, a flock of sheep. When a sheep gets lost from all the other sheep. Then I suppose that it has those religious connotations ... being an outsider, not being connected to something. That was a title that came right at the very end. I don’t know where that title came from ... Away from the Flock in a way is like: it is dead, so it is away from the living as well in that kind of way, the flock of living things. All those things, I never really look for a meaning, it is just if it feels right, gives a lot of the right kinds of meaning ... And Christ is often represented as a sheep in art.

(Quoted in Damien Hirst, pp.136–7.)

Hirst’s sculpture is entirely contemporary in its form and presentation, but the theme suggested by its title is far older, recalling a well-known pre-Raphaelite painting by the British artist, William Holman Hunt (1827–1910). Hunt’s painting, titled variously Our English Coasts 1852 (N05665), The Lost Sheep and eventually Strayed Sheep (final title in 1855), shows a flock of sheep nibbling grass at the edge of a cliff near Hastings in Kent. The beauty of the rural scene, illuminated by a particularly striking light, renders the religious symbolism implied in the notion of a straying flock applied to this painting ambiguous, as rather than stumbling in darkness (away from God) the sheep appear to be basking happily in the evening sun. Hirst’s reference to the religious subtext is similarly non-committal. As a child he attended a Catholic school and references to religious iconography are common in his work. Mother and Child Divided

subverts the familiar icon of mother Mary and baby Jesus with a violence Hirst found in religious imagery itself. He has recounted: ‘I have a lot of strong memories of religious imagery. We had a big illustrated bible and when I was young I would go straight to the crucifixion or severed head pages.’ (Quoted in Dannatt, p.62.) Since the early 1990s, Hirst has combined Christian iconography with the vocabulary of medical science which, for him, is another form of religion. He has equated the sheep’s isolation in Away from the Flock with the way that scientists have to cut things up and separate out elements in order to study them, saying that the work is, ‘about taking something out of the world and killing it to look at it ... It’s just that ... failure of trying so hard to do something that you destroy the thing that you’re trying to preserve.’ (Hirst and Burn, p.219.)

Away from the Flock has also been interpreted as a self-portrait (Hirst and Burn, p.219), standing as a celebration of artistic individuality that may be interpreted in several contradictory ways. Hirst has corroborated this, saying: ‘everything is a self-portrait, really. The shark, the diamond skull – they’re all self-portraits.’ (Quoted in Ossian Ward, ‘Damien Hirst’, Time Out, October 8–14 2009, p.14.)

Further reading:

Damien Hirst, I Want to Spend the Rest of My Life Everywhere, with Everyone, One to One, Always, Forever, Now, London 1997, reproduced p.293.

Damien Hirst and Gordon Burn, On the Way to Work, London 2001, reproduced p.85.

Eduardo Cicelyn, Mario Codognato and Mirta D’Argenzio, Damien Hirst, exhibition catalogue, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples 2004, pp.32 and 136, reproduced (first version) pp.134–5.

Elizabeth Manchester

October 2009

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Online caption

With this work Hirst is forcing us to focus on the humble sheep, an animal that has been providing us with food and warmth for centuries, transforming it from the mundane into something special. This strayed sheep highlights the importance of its title, ‘Away from the Flock’ a term we associate with religion, specifically Christianity, – "to leave the flock" is to leave behind the protection of the church. Hirst draws on precedents in earlier British art. In a famous painting by Holman Hunt, called ‘Our English Coasts’ or ‘Strayed Sheep’ 1852, the pre-Raphaelite artist shows straying sheep putting themselves at danger on the cliffs of southern England – a clear reference to religious decay. Although obviously dead and pickled in formaldehyde, the sheep in Hirst’s work looks oblivious to its fate and seems to be prancing with life.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- vulnerability(311)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- found object / readymade(2,631)

- tank(3)

- birth to death(1,472)

-

- mortality(49)

You might like

-

Damien Hirst Monument to the Living and the Dead

2006 -

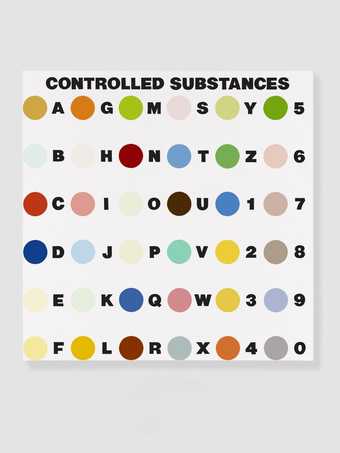

Damien Hirst Controlled Substance Key Painting

1994 -

Damien Hirst Trinity - Pharmacology, Physiology, Pathology

2000 -

Damien Hirst With Dead Head

1991 -

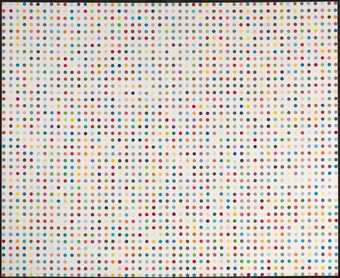

Damien Hirst Anthraquinone-1-Diazonium Chloride

1994 -

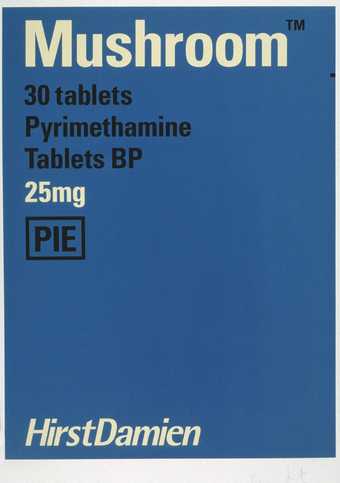

Damien Hirst Mushroom

1999 -

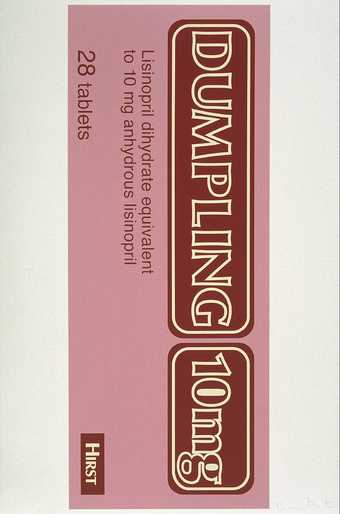

Damien Hirst Dumpling

1999 -

Damien Hirst All around the world

2002 -

Damien Hirst Oh my God ... and for those really stubborn stains!!!!!??*

2002 -

Damien Hirst Untitled

1992 -

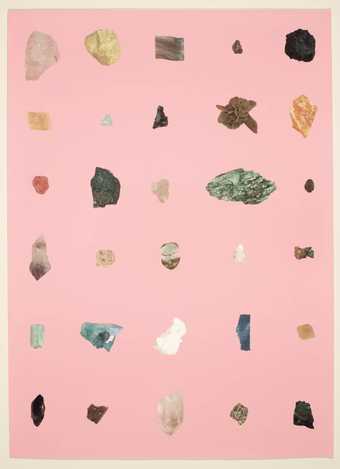

Damien Hirst Forms Without Life

1991 -

Damien Hirst The Acquired Inability to Escape

1991 -

Damien Hirst Life Without You

1991 -

Damien Hirst Mother and Child (Divided)

exhibition copy 2007 (original 1993) -

Damien Hirst Pharmacy

1992