Not on display

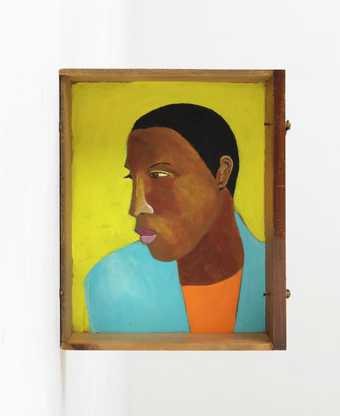

- Artist

- Lubaina Himid CBE RA born 1954

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on wood

- Dimensions

- Displayed: 3000 × 4500 × 1000 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Denise Coates Foundation on the occasion of the 2018 centenary of women gaining the right to vote in Britain 2019

- Reference

- T15156

Summary

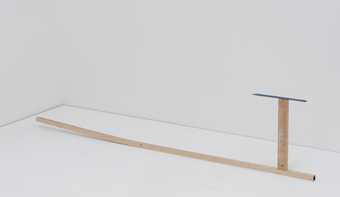

Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard 2014 comprises sixteen paintings on long wooden planks that have been repurposed by the artist. The planks are displayed in a line, leaning vertically at increasing angles against the gallery wall, so that their ends gradually rest further and further away from the wall. The artwork was created in response to an invitation to participate in the 10th Gwangju Biennial in South Korea in 2014, where it was first exhibited. The work was conceived and developed during an initial preparatory research trip to South Korea and physically created in the artist’s studio in Preston, Lancashire. Himid has revealed that it was partially inspired by her personal experience as a black woman travelling in South Korea, where she was repeatedly asked by various members of the public, ‘where are you really from?’ when she gave her nationality as British. Himid has described her encounter with one interlocutor: ‘I answered with a reply I’ve not had to use since the early 1980s in Britain – Zanzibar. This was all the woman needed, she seemed to want to know that I came from a place that black people should come from.’ (Lubaina Himid, email correspondence with Tate curator Laura Castagnini, 25 April 2018.)

Drowned Orchard was first presented alongside a series of paintings from the collection of the Gwangju Folk Museum, continuing Himid’s ongoing interest in working with museum collections. Each of the sixteen wooden planks is hand-painted with motifs drawn from both the natural and mythological worlds, as well as maritime history and the artist’s own visual vocabulary. Many of the images are inspired by iconography Himid encountered in the Gwangju Folk Museum and The National Folk Museum of Korea in Seoul where, she has said, ‘I found some of the most beautiful and strangely familiar objects I had ever seen’ (ibid.). Korean gods, fruits and fish are jumbled together with images of fictional African men, cowrie shells and ceremonial masks. Some of the paintings are devoted to a singular subject, such as a long dragon which snakes around the length of one panel. Others juxtapose iconography drawn from East African and South Korean cultural traditions to reveal a shared visual vocabulary. For example, one panel contrasts illustrations of roses and chrysanthemums, drawn from the artist’s own collection of Zanzibari Kangas (African garments made from printed fabric), with similar depictions of flowers she found in South Korea. Himid has written of Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard that it ‘attempts to evoke a deep unease with “the other”, a confusing encounter between cross cultural objects and patterns overlaid by an unrealistic desire to learn again how to start from nothing’ (Lubaina Himid, ‘Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard’, http://lubainahimid.uk/portfolio/drowned-orchard/, published online 2015, accessed 25 April 2018).

The theme of water dominates the imagery of Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard; not only are the wooden planks and the curving line of their overall display reminiscent of the hull of a boat, the work also features illustrations of the traditional South Korean ‘Geobukseon’ (turtle boat) military vessels and ‘Goryeo’ trading ships. These images are displayed besides a painting of a jug of flowing water: an icon used throughout Himid’s work to present a memorial to the Zong massacre of 1781 in which 133 African slaves were thrown overboard into the sea to drown. Elsewhere the artist has illustrated a sequence of maritime flags whose messages translate as urgent cries for help, such as ‘You should stop, I have something important to communicate’ and ‘Man overboard’. By bringing together such images, Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard draws connections between disparate histories of violence enacted on oceans, while also speaking to contemporary anxieties around border crossings. Such concerns are representative of Himid’s practice; throughout her diverse career she has explored historical representations of the people of the African diaspora and highlighted the importance of their cultural contribution to the contemporary landscape.

Further reading

Gilane Tawadros, ‘Beyond the Boundary: The work of Three Black Women Artists in Britain’, Third Text, vol.3, issue 8–9, 1989, pp.121–150.

Lubaina Himid, in conversation with Jane Beckett, ‘Diasporic Unwrappings’, in Marion Arnold and Marsha Meskimmon (eds.), Women, The Arts and Globalization: Eccentric Experience, London 2013, pp.190–222.

Jessica Morgan, Burning Down the House, exhibition catalogue, Gwangju Biennale 2014, p.83.

Griselda Pollock, ‘“How the political world crashes in on my personal everyday”: Lubaina Himid’s Conversations and Voices: Towards an Essay about Cotton.com’, Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry, no.43, 2017, pp.18–29.

Laura Castagnini

April 2018

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

Erika Verzutti Tarsila with Orange

2011 -

David Shrigley OBE Stop It

2007 -

Abraham Cruzvillegas AC6

2008 -

Abraham Cruzvillegas AC: Blind dates 1

2008 -

Abraham Cruzvillegas AC: Blind dates 2

2008 -

Abraham Cruzvillegas AC: Blind dates 4

2008 -

Abraham Cruzvillegas AC: Blind dates 3

2008 -

Julie Mehretu Mogamma, A Painting in Four Parts: Part 3

2012 -

Lubaina Himid CBE RA The Carrot Piece

1985 -

Thilo Heinzmann O.T.

2017 -

Pascale Marthine Tayou Poupée Pascale #17

2014 -

Pascale Marthine Tayou Poupée Pascale #15

2014 -

Monster Chetwynd Jesus and Barabbas (Odd Man Out 2011)

2018 -

Lubaina Himid CBE RA Man in A Shirt Drawer

2017–18 -

Rachel Harrison XLT Footbed

2013