Not on display

- Artist

- Tristram Hillier 1905–1983

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1502 × 1092 mm

frame: 1608 × 1206 × 70 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1984

- Reference

- T03865

Display caption

Like Nash and Wadsworth, Hillier was impressed by the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico, which he encountered while living in Paris in the 1920s. The Italian's plunging perspectives and unexpected juxtapositions evoked a mysterious world that led Hillier towards Surrealism. The scale of this anchor-structure is overwhelming, like a monument of unknown significance. It is one of several mysterious beach scenes with abandoned elements made in the 1930s.

Gallery label, December 2005

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Tristram Hillier 1905-1983

T03865 Variation on the Form on an Anchor

1939

Oil on canvas 59 1/8 x 43 (1502 x 1092)

Inscribed ‘Hillier' b.l. and ‘"VARIATION ON THE FORM OF AN ANCHOR" 1939' on top stretcher

Purchased from Alex, Reid and Lefevre (Grant-in-Aid) 1984

Prov: The artist's estate; Alex, Reid and Lefevre 1983

Exh: Paintings by Tristram Hillier, Arthur Tooth and Sons, May-June 1946 (19, repr.); Art in Britain 1930-40 Centred Around Axis, Circle, Unit One, Marlborough Fine Art, March-April 1965 (55, repr. p.37, dated 1938-9); A Timeless Journey, Tristram Hillier R.A. 1905-1983, Cartwright Hall, Bradford, June-July 1983, Royal Academy, Aug.-Sept. 1983, Ferens Art Gallery, Kingston-upon-Hull, Sept.-Oct. 1983, Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, Nov.-Dec. 1983, (14, repr. p.20 in col., dated 1936-7); Unit One: Spirit of the 30s, Mayor Gallery, May-June 1984 (28, repr., dated 1936-7)

Lit: [Nicholas Usherwood (ed.)], A Timeless Journey, Tristram Hillier R.A. 1905-1983, Cartwright Hall, Bradford 1983, pp.43-4, repr. p.20, dated 1936-7; William Feaver, ‘On Exhibition in Bradford and London', Observer, 10 July 1983, p.31; Tate Gallery Report 1984-6, 1986, p.77 repr., dated 1936-7

T03865 depicts a large black structure standing on a rocky outcrop against a background of sea and sky. The structure suggests a group of figures but is identified in the title as having been developed from the shape of an anchor.

Anchors first figured in Hillier's work of the early 1930s in mysterious scenes of discarded objects on beaches, an imagery which recalls the work of the French painter Jean Lurçat (see, for example, Lurçat's ‘The Signals', 1929 repr. Claude Roy, Jean Lurçat, Paris 1956, pl.26, as ‘Les Signaux'). One of the earliest works by Hillier of this kind is ‘Composition', 1933 (repr. Herbert Read, Art Now, 1933, rev. ed. 1936, pl.110) which shows an anchor and an abandoned wooden construction in front of a distant rowing boat and beach hut on a sea shore. By the mid 1930s Hillier developed the motif of an anchor into fantasy shapes of curves and hollows. The enlaced figurative structure in ‘Object on a Beach I', 1936 (coll. Ben P. Hillier, repr. Bradford exh. cat. 1983, p.31), for example, is as dark and seemingly metallic as the naturalistically depicted anchor before it. With similarly disturbing cavities in what appear to be the heads and torsos of the figurative group, the structure in T03865 seems closely related to the structure in ‘Object on a Beach I' and other related works of the mid 1930s.

The recurring motif of the anchor in Hillier's works reflected his love of boats and the sea. In the early 1930s he was a regular visitor to Cassis in the South of France where he often sailed in the company of Varda, a Greek painter, in a boat named ‘Lou Cat'. In his autobiography he said it was this boat and the escapades which he had with it that had first taught him to love the sea. Of his decision in this period to buy and live on a converted coasting vessel called a tartane

he wrote, ‘It was the sea I yearned for. My baptism with Varda had left its mark, and I found myself constantly longing for Lou Cat

and the smell of sail-cloth, rope and tar' (Tristram Hillier, Leda and the Goose, 1954, p.111).

Hillier found in the image of an anchor a perfect combination of a formally interesting shape and powerful symbolic meanings. In a statement published in the book produced by Unit One, a group of avant garde British artists to which he belonged in 1933-4, Hillier explained that he sought a balance in his paintings between subject matter and a response to plastic form:

The basis upon which I work varies according to my visual reaction. At times the plastic form revealed in a group of objects so completely subordinates for me any associative feeling that I know of no adequate means of expression but a use of purely abstract shapes; on other occasions so strongly am I impressed by the relation of one mass to another that, while depicting recognisable objects, I allow myself a deliberate distortion of perspective in order to emphasise the rhythm which I feel.

Generally, however, my aim is to build up a composition in a representative manner, assembling objects which have a mutual plastic complement and a similar evocative nature irrespective of their individual functions.

He went on to cite as an example of this ‘the sense of desolation engendered by the sight of a neglected and rusting anchor lying upon some deserted shore'. The affective content of such a scene, he wrote, was a ‘very natural form of symbolism' ([Herbert Read (ed.)], Unit One, 1934, p.69).

Over the following years Hillier's images of anchor-forms, become nightmarishly animate and mobile, showed his increased debt to Surrealist painting. Unlike many English artists, he was personally acquainted with leading French artists from the period in the 1920s when he lived in Paris. In an interview given in 1980 he said:

Of course I was very much influenced by the Surrealists in Paris and I knew them all. Chirico, I am sure, had a great deal of influence. Dali I never really liked but I admired him enormously as a craftsman and I think he had a great influence too on me. And then I was a great friend of Max Ernst through whom I knew ... the writers of the Surrealist period (Tate Gallery Archive, TAV 239A).

The looming figures in the black structure in T03865 recall particularly the hollow-headed curvilinear figures in Max Ernst's paintings of 1926-7, for example, ‘Two Persons and a Bird' (Julian Aberbach, New York, repr. [Werner Spies (ed.)], Max Ernst Werke 1925-1929, Cologne 1976, p.146 no.1073).

At the same time, the structure echoes the fluid-contoured sculpture of Henry Moore, a fellow member of Unit One. With its curves and hollows, ‘Reclining Figure', 1936 (Wakefield City Art Gallery and Museum, repr. [David Sylvester (ed.)], Henry Moore: Sculptures and Drawings 1921-1948, I 1957, p.110 no.175), appears to be a prototype of Hillier's anchor-figures and suggests how Moore also was concerned in this period to achieve a balance between abstract form and a recognisable subject matter. But whereas Moore employed the natural forms of weathered stone and the twisting shapes of bones and tree trunks, Hillier did not attempt to locate his work in the tradition of response to the English landscape. In featuring machine-made forms such as anchors, imaginatively transformed, Hillier was very much following the path of the French Surrealist writers who opposed a romantic, vitalist conception of nature.

A further continental influence upon Hillier's work can perhaps be found in Picasso's paintings of the late 1920s and early 1930s in which he transformed the human figure into a sometimes parodic, sometimes seemingly mutilated collection of skeletal and stone-like forms. In paintings such as ‘Seated Bather', 1930 (Museum of Modern Art, New York, repr. Christian Zervos, Pablo Picasso, Paris 1955, VII, p.125 as ‘Baigneuse assise au bord de la mer') Picasso combined the theme of suburban pleasures of a beach holiday with a disturbing image of a female figure that appeared to be half-flesh and half-bone. As a result of the influence exerted by the work of Surrealist artists and Picasso, the theme of hybrid beings was widespread in modern art of the 1930s.

On the back of T03865 are inscribed the title and a date, 1939. In a letter to the compiler dated 19 May 1988 Leda Hillier, the artist's widow, affirmed that both inscriptions are in the hand of her late husband. However, the proximity of this work to others of the mid 1930s in both style and subject matter and the apparent lack of any other works of 1939 with the motif of an anchor led Nicholas Usherwood in the catalogue of the recent Bradford exhibition of Hillier's work to suggest the work must have been painted in 1936-7. The explanation of how Hillier had mistaken the date, Usherwood wrote, might lie ‘in the fact that it was one of the works left behind in his rapid departure from France and shown for the first time only in 1946. It may therefore have been dated from memory after the war rather than at the time it was painted' (Bradford exh. cat. 1983, p.44).

If T03865 was not painted in 1939, the most likely date for it would be 1936, in the months between Hillier's return from Spain and his departure again in the summer for what was originally intended to be a brief holiday in Austria. In that case it might have been stored with a friend and recovered some time after Hillier's return to England after the fall of France in 1940. Although this might have occurred, there is no evidence that it did. Supporting the claim that the work was painted c.1936 is the fact that Hillier first developed the imagery of variations on the form of an anchor in the mid 1930s (although these images tend to be mobile, ghoulish forms rather than the static, almost monumental, structure depicted in TO3865). There is the further point that ‘Variations on the Form of an Anchor' is not painted in the meticulous manner or on the much-primed, smooth canvas surface that he adopted c.1937-8 as a result of his growing admiration for the craftsmanship of seventeenth century Dutch painting.

It seems unlikely that the painting was painted in the period between his departure from England in late 1936 and his settling in Normandy in 1938. Whilst in Austria Hillier met and married Leda Hardcastle and together they lived in Austria, then Italy and another area of France before setting up home in Etretat. In conversation with the compiler Mrs Hillier stated that the painting could not have been painted in the period between their meeting and their settling in Normandy because, at this time, all their possessions had to fit into their car and there would not have been room for such a large painting. She herself is certain that the work was painted in Normandy in 1939 and was surprised to learn that its date has recently been questioned. However, she is not certain whether her husband sent it to England before they left France in 1940 or whether it was one of the stock of works that their maid managed to hide in the cellar belonging to their lawyer during the War which were then imported to England in 1946. If it was one of that group of paintings, it could only have been painted in 1938-9. However, the relevant papers concerning the importation of Hillier's pre-War works cannot be found in the collection of the artist's family, his dealer or the Import Licensing Section of the Department of Trade and Industry or the Public Records Office. That being so, there is no evidence external to the painting itself that would support the date the artist himself gave the picture other than the firm belief of Mrs Hillier that the work was painted in Normandy.

While it is possible that the artist made a mistake in his dating of the painting, there is no reason to think that this was particularly likely. Certainly, the artist would have had no reason deliberately to post-date his work. In the absence of any strong counter indications, it appears reasonable to accept the artist's own judgement that the work was painted in 1939.

Circumstantial evidence in favour of this dating can be found in the passages in Hillier's autobiography which deal with the period he spent in Etretat. It clearly gave him great pleasure to be near the sea again. ‘The beach with its drying nets and jet-black fishing boats etched against the luminous Norman sky, and throwing deep translucent shadows upon the shingle, excited me enormously and formed the subject for what I consider some of the best paintings I have ever made' (Hillier 1954, p.156). In the summer of 1938 he spent time with Edward Wadsworth, then a painter of maritime scenes, and together they drew the ‘the rotting hulks and seaweed that we both so loved' (ibid.). In the autumn of 1939 he renewed his acquaintanceship with Georges Braque who lived close by in Varengeville. They went for long walks together over the cliffs and seashore, talking about the craft of painting. Hillier recalled in his book a particular occasion on which Braque, when discussing one of his own works, commented on the ‘living' quality he felt he had achieved in certain passages of black paint. Hillier wrote, ‘Any painter knows the difficulty of producing depth and translucency in the use of black, and although it was achieved by some of the Flemish School in a supporting contrast of colour, only Velasquez and Braque have managed to use it as a colour in itself. There, under the relentless light of the western sun the passages of pure black upon his canvas were as deep and mysterious as the ocean' (ibid., p.161). It may be coincidental but Hillier achieved the articulation of the intricate curving surfaces of the structure in T03865 by carefully judged sweeping movements of the paintbrush and varying numbers of layers of black paint.

If, as seems most likely, ‘Variation on the Form of an Anchor' was indeed painted in 1939, then it represented a late and final return by Hillier to the theme that had preoccupied him in the early and mid 1930s. In terms of the power of the imagery and sheer size of the work (it is the largest work Hillier ever painted), it can be seen as a culmination of the anchor series. In her letter to the compiler Mrs Hillier commented, ‘I think that my husband realised that he had achieved something in this work'.

Published in:

The Tate Gallery 1984-86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982-84, Tate Gallery, London 1988, pp.177-80

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- man-made(999)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- irregular forms(2,007)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- mystery(1,436)

- transport: water(8,015)

-

- anchor(61)

You might like

-

Edward Wadsworth The Beached Margin

1937 -

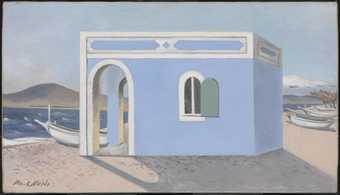

Paul Nash Blue House on the Shore

c.1930–1 -

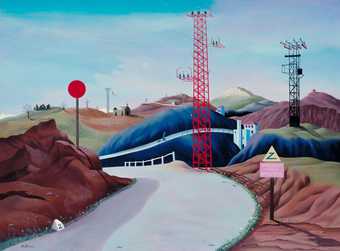

Tristram Hillier La Route des Alpes

1937 -

Tristram Hillier Harness

1944 -

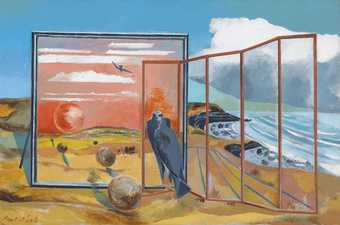

Paul Nash Landscape from a Dream

1936–8 -

Paul Nash Totes Meer (Dead Sea)

1940–1 -

John Wells Brimstone Moth Variation

1960 -

Tristram Hillier Alcañiz

1961 -

Paul Nash Equivalents for the Megaliths

1935 -

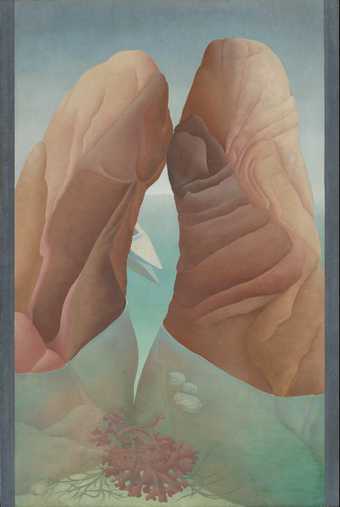

Ithell Colquhoun Scylla

1938 -

Edward Wadsworth Regalia

1928 -

Stanley William Hayter Ophelia

1936 -

Peter Lanyon Wreck

1963 -

Julian Trevelyan Basewall

1933 -

Tristram Hillier Composition 1933 (Interior)

1933