Not on display

- Artist

- Eva Hesse 1936–1970

- Medium

- Ink on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 278 × 216 mm

frame: 450 × 380 × 37 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Mrs Helen Charash, the artist's sister, through the American Federation of Arts 1986

- Reference

- T04151

Display caption

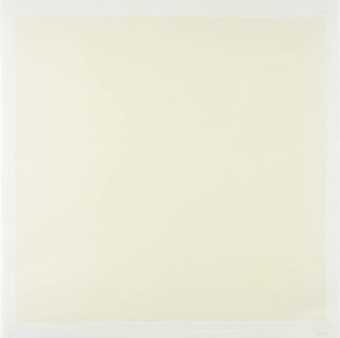

Hesse's work is predominantly monochrome and based on simple progressions or repetitions. This is one of a series of drawings on graph paper that she began to make in 1966, filling the tiny squares with single circles. The apparently limited formula yields unexpectedly non-mechanical and lightly textured drawings.

Gallery label, August 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Eva Hesse 1936-1970

T04151 Untitled

1967

Black ink 121 x 114 (4 3/4 x 4 1/2) on graph paper 278 x 216 (11 x 8 1/2)

Not inscribed

Presented by the artist's sister Mrs Helen Charash through the American Federation of Arts 1986

Prov: Mrs Helen Charash 1970

Exh: Eva Hesse: A Memorial Exhibition, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Dec. 1972-Feb. 1973, Albright Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, March-April 1973, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, May-July 1973, Museum of Modern Art Pasadena, Sept.-Nov. 1973, University Art Museum, Berkeley, Dec.-Feb. 1974 (66, repr.); The Alumni Fine Arts Show, Pratt Institute Gallery, New York, March-April 1977 (9, no cat.); Eva Hesse 1936-1970, A Retrospective of Works on Paper, Mayor Gallery, May-June 1979, Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, June-Aug. 1979 (25); Eva Hesse 1936-1970 Skulpturen und Zeichnungen, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hanover, Aug.-Sept. 1979 (64, repr. upside down); Eva Hesse; A Retrospective of the Drawings, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio, April-May 1982, The Renaissance Society, University of Chicago, Sept.-Nov. 1982, Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, Nov. 1982-Jan. 1983, Grey Art Gallery and Study Center, New York University, Jan.-Feb. 1983, Baltimore Museum of Art, March-April 1983, Des Moines Art Centre, Iowa, May-July 1984, University of Arizona Museum of Art, Aug.-Sept. 1984, Portland Center for the Visual Arts, Oregon, Oct.-Dec. 1984; Santa Barbara Museum of Art, California, Feb.-Mar. 1985 (72, repr.)

Lit: Ellen H. Johnson, ‘Drawing in Eva Hesse's work' in Eva Hesse: A Retrospective of the Drawings, exh. cat., Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin 1982, pp.9-26; Lucy Lippard, Eva Hesse, New York 1976, pp.72-7, fig.102

This is one of a series of drawings on graph paper which Hesse began to make in 1966 ‘where the tiny squares are simply filled with single circles or x's in pen and ink' (Lippard 1976, p.72). More informal circular shapes had appeared in Hesse's drawings for some years (see the drawings from 1961 repr. Lippard 1976, figs 13-17 and 19) and a number of her early German reliefs were based on circular, hemispherical or spherical forms, for example Lippard figs 46, 49, 54, 56, 59 and 60 (see also entry on T04154).

In the Spring of 1966, quite soon after her return from Germany, Hesse made some small rectangular reliefs featuring hemispheres of wound cord (Lippard 1976, figs 81, 82, 83 and 84) and Lippard records that in August 1966, on a visit to her friend Ethelyn Honig, in New Jersey, she began to make

the profoundly beautiful wash and ink circle drawings which continued through 1968... There are indications that during the Winter of 1965-66 she was searching for a drawing style that would parallel and give birth to new work the way the German ‘machine' drawings [see T04154] had produced the first reliefs.

... When she arrived at the circles, a motif already present in the three dimensional work, she may have missed the freedom of the more automatic imagery she had always used, but this could not have lasted long, since she extracted from this very simple formula - primarily rows of circles with or without centres - an endless internal vitality that made each one different (p.71).

Lippard divides the circle and wash drawings into two main types, the first consisting of rows of concentric circles ‘contained in a visible or invisible grid', and the second, larger or ‘target' circles, one or few to the page, also contained in rectangular compartments (p.72, see figs 91-100, 166-7, 227, 230-2). Besides these ink and wash series, Hesse also began another series of drawings on graph paper and T04151 belongs to this third set. In the mid sixties, Hesse knew and admired the work of a number of artists who were associated with minimal and conceptual art (for example, Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre, Mel Bochner, Dan Graham and Dan Flavin) but as Lippard points out, ‘even in her graph paper series (also begun in 1966) where the tiny squares were filled with single circles or x's in pen and ink..., the effect is not one of [minimalist] detachment' p.72. Lippard describes the ‘lightly textured' non mechanical surfaces of the drawings, citing four examples dating from 1967 including T04151 (figs 101-4). Like T04151, two of the remaining works consist of blocks of ink circles - in the case of fig.104 only part of the rectangle has been filled in and each circle is attached to a short pen line, suggesting a string or other attachment (a device which Hesse extended into three dimensions in the Tate's sculpture, ‘Addendum' 1967, see Tate Gallery Acquisitions 1978-80, 1981 T02394

pp.102-4)). Fig.101 consists of a block of small pen ‘x's' also drawn on graph paper.

Lippard describes Hesse's work of 1967 as ‘the most geometric, serial and minimal of her career' (p.84) Her work in two and three dimensions was predominantly grey in colour and based on simple serial progressions or repetitions; see, for example, the grid-based reliefs using regularly spread lengths of rubber tubing (Lippard 1976, figs 117-20 and, particularly, in relation to the grid drawings such as T04151, the ‘washer' reliefs and drawings illustrated, figs 121-4, 126, 127, 128.). Lippard writes of the ‘washer' works

All of the ‘washer pieces' resemble each other, although some are actually made of grommets rather than steel or rubber washers; these were laid in tight rows to cover completely a wood surface and then the whole was covered in sculp metal. They recall the black circle drawings and the graph-paper drawings in both image and obsessiveness. They are almost drawings, or paintings, themselves, having little sculptural identity; even the boards are very thin, as though to further de-emphasize their volume (p.90).

Lippard reproduces other variants on the circle within a square motif, (for example ‘Accession II' 1967 fig.143, one of a series of box pieces made of grid perforated aluminium; ‘Schema' 1967 fig.157, consisting of a grid of semispheres on a sheet of latex). Lippard points out that Jasper Johns was an important influence on a number of younger artists in the mid sixties, and finds this influence reflected in Hesse's washed circle drawings and in the washer reliefs (p.197). Her interest in serial arrangement was, according to Lippard ‘prompted by Sol LeWitt and Donald Judd (p.201). Agnes Martin is also cited as having in common an approach to structure, for example the grid (p.203).

In her essay ‘Eva Hesse, The Early Drawings' (in Eva Hesse - The Early Drawings and Selected Sculpture, exh. cat., Rose Art Museum, Waltham 1985) Susan L. Stoops writes of the origins of the grid format in Hesse's drawings and sculpture:

It has been suggested that Hesse came upon the grid, a form which was to characterize her most minimal (and perhaps most familiar) sculpture and drawings from 1966-67, ‘accidentally' through the discovery in December 1964 of a piece of junk screening that subsequently became her first piece of sculpture. But one has only to consider several drawings and collages from 1963 to realize that the underlying essence of the grid - the repeated rectangle - was already being used to organize and structure her two-dimensional work (p.7).

In her catalogue essay on Hesse's drawings, Ellen Johnson remarks on the ‘personal touch' revealed in T04151 and related drawings:

The juxtaposition of several examples of the exactingly drawn miniscule circles within squares demonstrates their minor but telling variations. Two (nos 72 [T04151] and 73) are simply circles within squares while in the other two (nos.74 and 75) a short line connects each circle to the one below it. Besides the variation in format and in the scale of the single circle to the whole image and the image to the page, paradoxical and shifting illusions occur. In no.73 the black square tends to dominate; in no.72 the white circle comes forward, but there are continual fluctuations within each. As is perceptible on close inspection, the elements within the squares are never identical in shape, density of ink or width of line. For these reasons, the graph drawings, even the most precisely controlled, have a shimmering movement over the surface; while confined in grids, the individual units vibrate like atoms in a crystal lattice (p.22).

Johnson attributes ‘this surface activation to a compulsion to repeat the same action of the hand' to ‘a painterly impulse which had gone underground when she gave up painting as such in 1965' but which was to re-emerge more fully in her last works.

Published in:

The Tate Gallery 1984-86: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions Including Supplement to Catalogue of Acquisitions 1982-84, Tate Gallery, London 1988, pp.169-71

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- geometric(3,072)

You might like

-

Robert Ryman [no title]

1972 -

Robert Ryman [no title]

1972 -

Robert Ryman [no title]

1972 -

Robert Ryman [no title]

1972 -

Robert Ryman [no title]

1972 -

Robert Ryman [no title]

1972 -

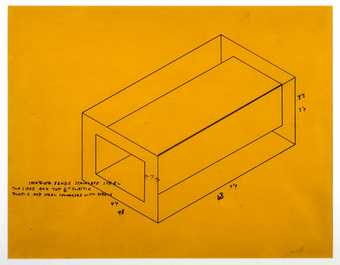

Donald Judd [no title]

1974 -

Donald Judd [no title]

1974 -

Donald Judd [no title]

1974 -

Ad Reinhardt [no title]

1964 -

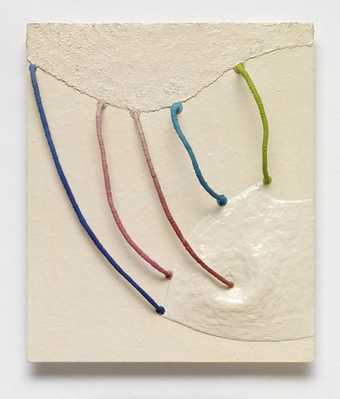

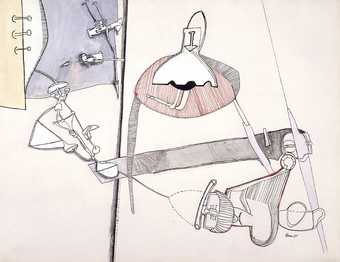

Eva Hesse Tomorrow’s Apples (5 in White)

1965 -

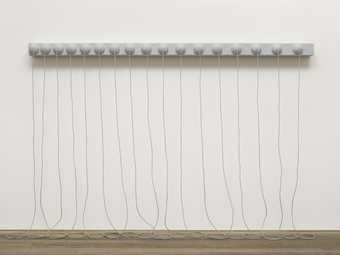

Eva Hesse Addendum

1967 -

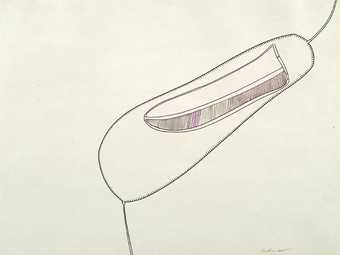

Eva Hesse Untitled

1965 -

Eva Hesse Untitled

1965 -

Donald Judd Untitled

1967 or 1968