Not on display

- Artist

- Dame Barbara Hepworth 1903–1975

- Medium

- Cumberland alabaster on marble base

- Dimensions

- Object: 230 × 455 × 189 mm, 11.1 kg

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1993

- Reference

- T06676

Summary

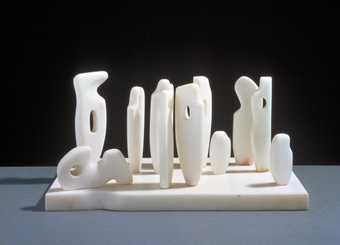

Mother and Child 1934 is a small abstract stone sculpture by the British artist Barbara Hepworth, which is horizontal in configuration and has an undulating and biomorphic shape. The work’s title suggests that the sculpture is loosely figurative, with the larger shape that comprises most of the sculpture representing the reclining figure of the mother, and the smaller shape that rests on top of it a child held in her embrace. Although they are independent sculptural elements, both mother and child appear to have been carved from the same piece of Cumberland alabaster. Both parts are a warm brownish-grey colour and have black, grey, white and brown veining running across them. Each of the figures has a nodule-shaped head with a single white eye drilled into it, and there is a large opening in the centre of the work that denotes the space beneath the mother’s arm as it rests upon her leg. The work sits off-centre on a thin rectangular base made from white-grey marble.

Hepworth made this sculpture in 1934 in her studio at The Mall, Parkhill Road, in Hampstead, London. Both she and the British artist Henry Moore used Cumberland alabaster in their work during the period 1930–4 (see, for example, Moore’s Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure 1934, Tate T02054). Both artists were given the stone by fellow sculptor John Skeaping, who had purchased lumps of it that had been ploughed up by a Cumbrian farmer.

Mother and Child was produced using a sculptural practice known as direct carving. First introduced by the French artist Constantin Brancusi in 1906, the technique was further developed by Hepworth, Moore, Skeaping and the British painter and sculptor Ben Nicholson in the 1920s and 1930s. Direct carving is a process in which no models or sculptural maquettes are used to plan the work, but rather the final form of the sculpture emerges through the act of carving the material (see the discussion of Hepworth’s approach to direct carving in Curtis 1994, p.15). Through this technique, these artists emphasised the inherent properties of the materials, and the marble, stone and wood that they used was rubbed and polished in order to enhance its natural texture, colours and markings. They believed that direct carving, as well as the use of simple forms and organic compositions, brought them closer to a ‘primitive’ or non-Western approach to making art and encouraged a sensitive and instinctive relationship to the landscape. Hepworth and Moore were inspired by objects that they studied in the collections of the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Hepworth owned some ancient artefacts, including those from the Neolithic and Cycladic eras.

The motif of the mother and child recurs frequently in Hepworth’s work during the late 1920s and early 1930s (see, for example, Mother and Child 1927, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; Infant 1929, Tate T03129; Pierced Form 1931, destroyed; and Mother and Child 1934, Wakefield Art Gallery, Wakefield). This may reflect changes that were occurring in Hepworth’s own life at the time: in 1929 she gave birth to her first son Paul Skeaping (son of John Skeaping) and in 1934, the same year this work was made, she became the mother of triplets with Ben Nicholson. Hepworth commented in 1943 that ‘There was a turbulent period 1933–4 … but I stand by [the works]. They mattered a lot emotionally and sculpturally’ (quoted in Gale and Stephens 1999, p.48). Describing this period of Hepworth’s practice in the Spectator in 1934, the painter and writer Adrian Stokes stated

So poignant are these shapes of stone, that in spite of the degree in which a more representational aim and treatment have been avoided, no one could mistake the underlying subject of the group … Miss Hepworth’s stone is a mother, her huge pebble its child.

(Quoted in Gale and Stephens 1999, p.47.)

Having acknowledged in 1931 that her work was ‘tending to become more abstract’ (quoted in Gale and Stephens 1999, p.45), in Mother and Child Hepworth employed two innovative approaches to abstraction. According to the curator Matthew Gale, Mother and Child was radical, at least in Britain, for the fact that it consisted of a multi-part composition as opposed to a ‘single integral sculpture mass’ (Gale and Stephens 1999, p.45). Equally significant, Gale has claimed, was Hepworth’s inclusion of a large hole at the centre of the composition, a technique that she first adopted in 1931 with Pierced Form. Gale has stated that ‘for Hepworth the piercing of Mother and Child went beyond a formal device. It carried a conceptual value, with the suggestion that the child had come from – and outgrown – the vacant space in the centre of the mother’s body’ (Gale and Stephens 1999, p.47). Furthermore, the art historian Anne Wagner has noted the psychoanalytic implications of Hepworth’s sculpture, discussing the work in relation to the anxieties, such as that of separation, that can exist within the mother-infant relationship (see Gale and Stephens 1999, p.48).

Further reading

Penelope Curtis, ‘Barbara Hepworth and The Avant-Garde of the 1920s’, in Penelope Curtis and Alan G. Wilkinson, Barbara Hepworth: A Retrospective, exhibition catalogue, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool 1994, pp.11–31, reproduced p.48.

Penelope Curtis, Barbara Hepworth (St. Ives Artists), London 1998.

Matthew Gale and Chris Stephens, Barbara Hepworth: Works in the Tate Gallery Collection and the Barbara Hepworth Museum St. Ives, exhibition catalogue, Tate Gallery, London 1999, reproduced p.47.

Judith Wilkinson

December 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Hepworth’s child perches on the knee of its reclining mother, implying a continuity of material. Yet, looking at the veining of the stones, we can see that they are separate forms. In the early 1930s, Hepworth was starting to create more complex, multi-part sculptures. She developed a range of new abstract forms by carving holes into her works. This hole suggests that the child has come from – and outgrown – the vacant space in the centre of the mother’s body.

Gallery label, May 2021

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Dame Barbara Hepworth

1903-1975

T06676 Mother and Child 1934

BH 58

Cumberland alabaster on marble base 220 x 455 x 189 (8 5/8 x 7 15/16 x 7 7/16); weight 11.1 kg

Purchased from Browse & Darby with assistance from the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1993

Provenance:

...; anon. sale [Bertha Jones] Sotheby's, London, Modern British Drawings, Paintings and Sculpture, 1 Nov. 1967 (176, repr.); bt Mrs Edna Cohen, from whom bought by Browse & Darby

Exhibited:

Unit One, Mayor Gallery, London, April 1934 (35, as 'Composition (Grey Cumberland Alabaster)'), Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, May-June (41), Platt Hall, Rusholme, Manchester, June-July (15), Hanley City Art Gallery & Museum, Aug.-Sept., Derby Corporation Art Gallery, Swansea, Belfast Municipal Art Gallery & Museum (as Composition)

?St Ives Society of Artists Summer Collection, New Gallery, St Ives, summer 1946 (?133)

19th and 20th Century Painting, Drawing and Sculpture, David W. Hughes, London, Summer 1968 (22, repr. in col. [p.17])

Barbara Hepworth 1903-75, William Darby, London, Nov. 1975 (1, repr. mistakenly as 'collection: B. Jones')

Barbara Hepworth: A Retrospective, Tate Gallery Liverpool, Sept.-Dec. 1994, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Feb.-April 1995, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, May-Aug. (17, repr.in col. p.48)

Design of the Times; One Hundred Years of the RCA, Royal College of Art, London, Feb.-March 1996 (no number)

Carving Mountains: Modern Stone Sculpture in England 1907-37, Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, March- April 1998, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, May-June (24, repr. p.71)

Literature:

J.P. Hodin, Barbara Hepworth, Neuchâtel and London 1961, p.163, no.58, repr.

Alan G. Wilkinson, 'The 1930s: "Constructive Forms and Poetic Structure"' in Penelope Curtis and Alan G. Wilkinson, Barbara Hepworth: A Retrospective, exh. cat., Tate Gallery Liverpool 1994, pp.47, 50

Alex Potts, 'Carving and the Engendering of Sculpture: Stokes on Hepworth' in David Thistlewood (ed.), Barbara Hepworth Reconsidered, Liverpool 1996, p.48, repr. p.50

Anne M. Wagner, '"Miss Hepworth's Stone Is

a Mother"' in Thistlewood 1996, pp.66-7

Claire Docherty, 'Re-reading the Work of Barbara Hepworth in the Light of Debates on "the Feminine"' in Thistlewood 1996, p.166

Un Siècle de Sculpture Anglaise, exh. cat., Galerie national du Jeu de Paume, Paris June-Sept. 1996, p.457

Reproduced:

Herbert Read (ed.), Unit I: The Modern Movement in English Architecture, Painting and Sculpture, London 1934, p.24, pl.5

Tate Gallery Report 1992-4, London 1994, p.30 (in col.)

With the emergence of her multi-part sculptures during 1933-4, Barbara Hepworth initiated (in Britain at least) the abandonment of the convention of the single integral sculptural mass. This paralleled her sometimes hesitating experiments with abstraction and an increasingly internationalist outlook, aspects brought together in her membership of the Parisian group Abstraction Création from 1933. Already two years earlier - the year of her first holed piece, Pierced Form, 1931 (BH 35, destroyed, repr. Hodin 1961, pl.35) - she saw that her output was 'tending to become more abstract' (letter to Ben Nicholson post-marked 2 Oct.1931, TGA 8717.1.1.56). By 1934, when Mother and Child

was made, this process was being explored theoretically in her writings, especially her contribution to Unit One, and reinforced by like-minded supporters.

The theme of the mother and child was arguably Hepworth's most consistent in this period, even if, significantly, many examples were initially exhibited under more anonymous titles such as Carving

or Composition. The sequence of works, in which Mother and Child

falls towards the end, may be divided roughly into three stages. First, the theme was tackled in a number of direct carvings of the preceding years, in which the block was characteristically evident; these included Mother and Child, 1927, (BH 6, Art Gallery of Ontario, repr. Barbara Hepworth, Tate Gallery Liverpool, p.21). Second, there were the organic alabasters of 1931-2, such as Two Heads, 1932 (BH 38, Pier Gallery, Stromness, repr. Read 1952, pl.20b), in which the integrity of the sculpture and some reference to the body were maintained. The multi-part sculptures begun during 1933 constitute the third phase; they included the lost grey alabaster Figure (Mother and Child), 1933 (BH 52, repr. Hodin 1961, pl.52) - first exhibited as Composition

- in which the child was famously pebble-like. Such upright (seated or standing) pairings were supplemented by horizontal arrangements, of which one of the earliest was the undulating abstraction of the blue marble Two Forms, 1933 (BH 54, former collection L. Grahame-Wigan, repr. ibid. no.54) - first shown as Carving. In the following year, at least three still organic but more referential reclining alabasters were made, including the Tate's sculpture, itself first entitled Composition. Very similar to it, because of the child perched on the knee, is Large and Small Form, 1934 (BH 59, Pier Gallery, Stromness, repr. ibid., no.59); while in the other Mother and Child, 1934 (BH 57, private collection, repr. ibid., no.57), the child nestles at the mother's side. In all these works, the two parts were, at least by implication, cut from the same block, a practice which had important psychological resonances.

Within this sequence the Tate's Mother and Child

is materially and formally consistent. As with the other horizontal works of 1934, there is a visible consonance in the form of the child as a miniature echo of the mother. The warm grey alabaster of the child is close in colour to the adjacent knee to which it is fixed, suggesting the continuity of material if not of the veining. The waves of stone, slightly angled across the length (an effect more obvious from above), and the undulating outline of the whole offers a variant of Two Forms, 1933 (BH 54). The nodule heads follow an established pattern, and both have single drilled eyes which appear to have been originally whitened (Tate Gallery Conservation Files). The choice of stone can be linked to Henry Moore's recollection that John Skeaping had introduced his friends to Cumberland alabaster, having been sold lumps of the stone ploughed up by a farmer (Tate Gallery Acquisitions 1976-8, 1979, p.117). Hepworth's period of carving alabaster - whether the grey-brown Cumberland or creamier varieties such as that used for Sculpture with Profiles, 1932 (Tate Gallery T06520) coincided with Moore's use of it during 1930-4, for such works as Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure, 1934 (Tate Gallery T02054). The soft stone of Mother and Child

has developed a major fault through the mother's back and foot, while both heads have suffered stun marks and small scratches; the surface has been cleaned and the single dowels, from child to mother and from mother to base, re-secured (Tate Gallery Conservation Files). The mother's hip is pinned, with the elbow resting on the base and the foot is lifted free; in the sculptor's photographic albums (TGA 7247.7; comparative illustration) this gap is deliberately lit.

The same photograph shows the sculpture on a base quite different from that to which it is now fixed. The front of the earlier base was roughly broken off to form a sloping shelf and to allow a textural variety. Furthermore, this base framed the figure closely at elbow and foot. The elongation of the present base beyond the foot, seems to date from the ownership of Bertha Jones; the fate of the original base is not known, nor is it known if Hepworth sanctioned the change. In any case, the effect is to present the mother asymmetrically, placing the emphasis on the child and fundamentally altering the balance and, consequently, the experience of the sculpture.

In addition to the juxtaposition of separate elements, Hepworth introduced her still innovatory piercing in the main stone of Mother and Child. This epitomised the tendency in 1932-4 towards organic abstraction. In common with nearly all its precedents, the hole appears to be derived formally from the space under an arm. In Mother and Child

it achieved an importance comparable to that in the first Pierced Form, as it was at the centre of the composition when the work was still mounted on the original base; although this is no longer the case, the hole remains crucial to the undulating rhythm. Like the organic form, the introduction of piercing anticipated Moore's use of these devices for the treatment of the figure. He would transform this into a figurative equivalence with landscape in such works as the Hornton stone Recumbent Figure, 1938 (Tate Gallery N05387). For Hepworth, the piercing of Mother and Child

went beyond a formal device. It carried a conceptual value, with the suggestion that the child had come from - and outgrown - the vacant space in the centre of the mother's body. The psychological empathy and the physical dependence (and independence) of this relationship were repeatedly addressed in her exploration of the theme, which became more acute following her son Paul's birth in 1929. In early 1934, Hepworth became pregnant again and her triplets were born in October.

Hepworth's 1933 Mother and Child

works were shown in her exhibition at the end of that year (Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Alex. Reid & Lefevre Ltd, Oct.-Nov. 1933) and elicited Adrian Stokes's review in The Spectator

('Art: Miss Hepworth's Carving', Spectator, Nov.1933, p.621; reprinted in Lawrence Gowing, ed., The Critical Writings of Adrian Stokes, vol.1, 1930-37, 1978, pp.309-10). They were close friends and in the following month the writer helped the sculptor with her contribution to Unit One

(Hepworth letter to Ben Nicholson, post-marked 8 Dec. 1933, TGA 8717.1.1.157). In his review, Stokes favoured her sympathy in carving stones, so that 'their unstressed rounded shapes magnify the equality of radiance so typical of stone'; he saw pebbles as 'essential shapes' achieved through smoothing and rubbing. This served as a preliminary to his discussion of Composition, a work identifiable from his description with the lost Figure (Mother and Child), 1933 (BH 52). His discussion of the hierarchical and implicitly psychological relationship between the two elements was deliberately couched in more widely applicable terms:

The stone is beautifully rubbed: it is continuous as an enlarging snowball on the run; yet part of the matrix is detached as a subtly flattened pebble. This is the child which the mother owns with all her weight, a child that is of the block yet separate, beyond her womb yet of her being. So poignant are these shapes of stone, that in spite of the degree in which a more representational aim and treatment have been avoided, no one could mistake the underlying subject of the group. In this case at least the abstractions employed enforce a vast certainty. It is not a matter of a mother and child group represented in stone. Miss Hepworth's stone is

a mother, her huge pebble its child.

(Stokes 1933, ibid.)

Both the discussion of the pebble-like form of the stone and the play between representation and abstraction are applicable to Mother and Child, 1934. More particularly, the psychological interpretation of the separation of child from mother was of crucial and - the writer implies - universal significance. From Hepworth's response to his assistance over Unit One in the following month, it may be assumed that she found his interpretation acceptable. Writing to Nicholson, she claimed:

His [Stokes's] whole life is built on a very sensitive perception of other people's thoughts. His thought is not that of limitation but of this: 'Identity is the reflection of the Spirit, the reflection in multifarious forms of the living principle - love' which sees the individual beauty & differences of flowers stones & people & cares for & loves each identity & understands.

(letter postmarked 6 Dec.1933)

Several scholars have discussed Stokes's article, as much in terms of his own theories of sculpture as for the light it sheds on Hepworth's work. Its revelation and contradiction, in the case of the woman artist, of his explicit gendering of the process of sculpture - whereby the male carver transforms the female matter - has been the focus of Alex Potts (Potts 1996, pp.43-52). In a broader discussion, Anne Wagner has seen the article in the light of Stokes's course of analysis with Melanie Klein (Wagner 1996, pp.57-9). Both scholars have noted that this had only just begun in 1933, but the psychoanalyst's concentration upon infancy appeared to be especially pertinent to Hepworth's work. In such papers of the late 1920s as 'Early Stages of the Oedipus Conflict' (International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, vol.9, 1928; reprinted in Juliet Mitchell ed. The Selected Melanie Klein, Harmondsworth 1986, pp.69-83) and 'Infantile Anxiety Situations Reflected in a Work of Art and the Creative Impulse' (International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, vol.10, 1929; reprinted in ibid. pp.84-94) Klein discussed the coincidence of sadistic desire and the Oedipus complex within the infantile psyche. In particular, she posited 'infantile anxiety situations' in the female psyche centred upon the internal organs: a desire to remove the sexual and reproductive organs - to deprive the mother of sex and prevent further children - and a conflicting fear of an assault by the mother on the girl's organs, depriving her in turn of children.

The sculptor's concentration on the mother and child theme and its conflation with the pierced stone takes on particular resonances in the light of Klein's theories. Some of these were hinted at by Stokes, but Wagner has taken the analysis further. Proposing Hepworth's carving as 'an act of self-inscription' (Wagner 1996, p.60), Wagner observed that Klein's theories could show them to be thematically more complex than formal discussion had hitherto allowed. She concluded: 'These are bodies made into objects which may present dangers or threats, or themselves be threatened ... They add up to a testing and verification of a limited range of fantasmatic fears and hopes concerning the female body's presence, its contents and its voids' (ibid., p.66).

A decade after completing Mother and Child, Hepworth reviewed her own work in a letter to E.H. Ramsden, who was writing an article for Horizon

(vol.7, no.42, June 1943, pp.418-21). The letter provides some support for Wagner's reading, not least because of its acknowledgement of 'emotion, tension and so on' in the works of the 1930s. In a passage interspersed with sketches, Hepworth acknowledged: 'There was a turbulent period 1933-34 ... Ben always kicks up a fuss when he sees the few turbulent photos such [as]' sketches of the lost Figure (Mother and Child) , 1933 (BH 52) and Large and Small Form, 1934 (BH 59) 'etc. but I stand by them. They mattered a lot emotionally and sculpturally' (4 April 1943, TGA 9310). In view of the fact that both sketched works belong to the mother and child sequence of organic alabasters, the memory of turbulent emotion is telling. In retrospect, they may also have been regarded as sculpturally turbulent in contrast to the purity of the ensuing abstractions of the mid 1930s.

Matthew Gale

April 1997

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- reclining(814)

- woman(9,110)

- child(1,324)

- family(602)

-

- mother and child(394)

You might like

-

Dame Barbara Hepworth Group II (People Waiting)

1952 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Figure

1933 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Three Forms

1935 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Forms in Echelon

1938 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Group I (Concourse) February 4 1951

1951 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Infant

1929 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Seated Figure

1932–3 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Three Forms (Carving in Grey Alabaster)

1935 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Sculpture with Profiles

1932 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Two Forms

1933 -

Dame Barbara Hepworth Model for ‘Project for Waterloo Bridge: The River’

1947