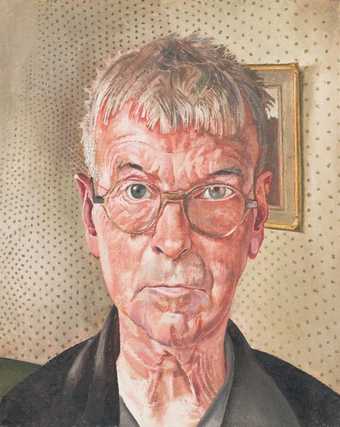

Euan Uglow Georgia 1973 British Council © Estate of Euan Uglow, courtesy of Marlborough Fine Art

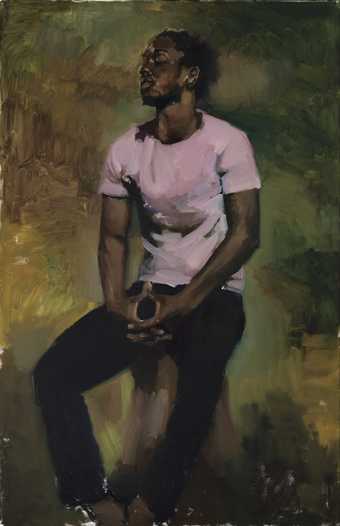

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

The Generosity

(2010)

Tate

1. With a close eye for detail

'Nobody has ever looked at you as intensively as I have,' Euan Uglow once told a sitter. This level of attention is clear to see in Uglow's portraits. They are the result of careful observation and equally painstaking composition. He described himself as a perfectionist, directing the pose of models he painted to create a controlled and precise appearance of the body.

Uglow was influenced by his tutor at Camberwell School of Art, William Coldstream, who approached figurative painting with an almost mathematical rigour. Uglow's preparatory drawings are filled with mathematical formulae and references to principles like the Golden Ratio. He would carefully mark the setting of the painting in his studio with wire or string, which helped him get a better sense of the space that he was painting and how his subject was positioned within it. He would map out this web of perspective on his canvas using small pencil marks (and sometimes chalk marks on the flesh of his models). These crosses and grids are still visible in most of his works; when asked why he never removed them, Uglow said that he never knew when he might need to refer to them again.

Although Uglow painted people with a very meticulous and rational approach, his works are still full of sensuous power.

I'm painting an idea not an ideal. Basically I'm trying to paint a structured painting full of controlled, and therefore potent, emotion.

Euan Uglow, 1989

2. Exposed

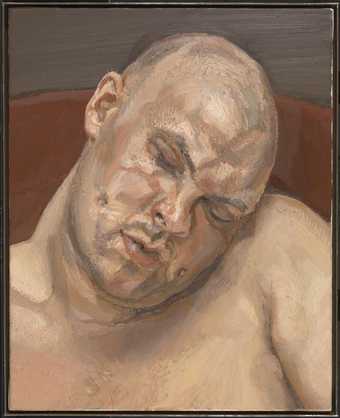

As far as I am concerned the paint is the person. I want it to work for me just as flesh does

Lucian Freud, 1982

Lucian Freud’s portraits are unapologetic celebrations of the human body, painted with a focus on physicality that had rarely been seen before in the genre of nude painting. He approaches his models like a photographer, homing in on details of his subjects in a closely cropped and uncompromising way.

Lucian Freud

Leigh Bowery

(1991)

Tate

Just look at this painting of the performer Leigh Bowery. Freud has focused uncomfortably closely on the subject’s face and shoulders, but the subject feels strikingly naked nonetheless. By applying paint in varying textures across the canvas – in some places smooth, in others thickly yet delicately built up – Freud paints flesh that you almost feel you can touch.

Bowery was a very fitting subject for Freud. Both artist and performer knew that bodies still had the power to shock and offend viewers. He was an extremely physical performer with a large stature, who would mould and tape his body, mask and smear his face with make-up to express an androgynous identity. 'The way he edits his body,' Freud said, 'is amazingly aware and amazingly abandoned.' Interestingly, Freud chose to paint Bowery out of the costume so closely associated with his public persona. This tender nude portrait emphasises his humanity and vulnerability.

3. Inside Out

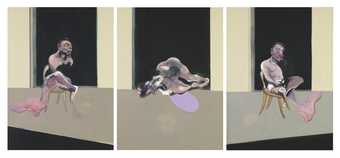

Francis Bacon Portrait 1962 Private Collection © The Estate of Francis Bacon All Rights Reserved, DACS 2018

What I want to do is to distort the thing far beyond the appearance but in the distortion to bring it back to a recording of the appearance

Francis Bacon, 1966

For some artists, the nude body is not nearly naked enough. In this portrait of his lover Peter Lacy, Francis Bacon shows the internal organs seemingly bursting through the skin. This was the first example of what would become a common motif in Bacon’s work. This grisly fascination goes back to Bacon’s childhood, when he had become entranced by the sight of carcasses hanging in butchers’ shops.

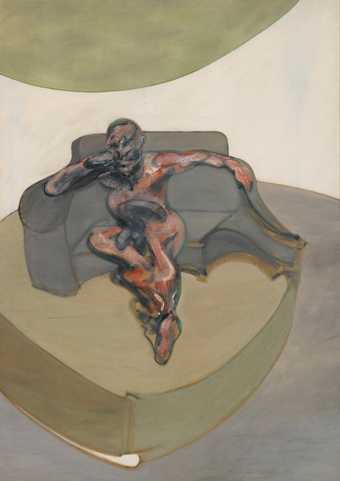

4. As part of a story

The greatest problem all my life has been the inability to speak my mind – to speak the truth […]. Therefore the flight into storytelling. You paint to fight injustice

Paula Rego, 1994

At a time when a whole generation of women artists were turning their back on figurative painting - seeing it as a masculine activity - Paula Rego became something of a role model. She pointed to a different way of painting the body, one that combined realistic depiction with allegorical painting, folklore, fairy tales and other traditions of storytelling.

Paula Rego

The Betrothal: Lessons: The Shipwreck, after ‘Marriage a la Mode’ by Hogarth

(1999)

Tate

Her triptych after William Hogarth, for example, is a response to the eighteenth century painter’s satirical narrative series, Marriage A-la-Mode, c.1743. The series is a story of class aspirations and an ill-matched marriage ending in bloody tragedy. Rego updates the story to twentieth-century Portugal, switching around genders and transforming the story into one of female suffering and fortitude. Still, Rego paints from life - or a version of it. In her studio she paints from elaborately constructed tableaux, which combine live models, props, stage sets and mannequins.

5. Using your imagination

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye Coterie Of Questions 2015 Private Collection © Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, courtesy of Corvi-mora

There’s something about nature, about the senses, about history, that is all encapsulated in oil paint … It feels closer to the body … it forms a skin. It moves like skin when you paint

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, 2014

The people in Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings don’t exist. Rather than painting from life, she works from 'bits and pieces': photographs, drawings, memories of real-life encounters or pages from her scrapbook. From these elements, Yiadom-Boakye creates paintings of ambiguous, invented figures in an uncertain setting. She paints each work in a single day, on the basis that coming back to the work at a later point never improves its. She prefers not to see these paintings as portraits, however. Her focus is much more 'on the actual nature of the painting itself and what that [does] to the subject rather than what the subject [does] to the painting.'