Aubrey Williams

Cosmic Storm

(1977)

Tate

Aubrey Williams (8 May 1926 – 17 April 1990) was a Guyanese artist, notable for his interest in Abstract Expressionist style and the iconography of indigenous people in Guyana. Though he has gained greater recognition in recent years, during his lifetime he had limited critical success and fought for better representation for Caribbean artists as a founding member of the British Caribbean Arts Movement.

Here are five things to know about this ground-breaking artist.

1. His style is influenced by his early life in Guyana

Some of the major influences in Aubrey Williams’ work can be traced back to his early life in Guyana. Williams was born in 1926 in Georgetown, Guyana’s capital, while it was still a British colony. As noted by ART UK, though Williams took up drawing from a young age, including being taught by a restorer of religious paintings in Guyanese churches, one of his most significant influences can be traced back to his job in the late 1940s. With much of Guyana’s economy reliant on the sugar industry, Williams supported his art practice by training as an agronomist (an expert in the science of soil management and crop production). Working as an agricultural field officer, while stationed in North Guyana between 1947 and 1949, Williams became associated with the Warrau tribe who resided there. Through learning their language, observing their customs and rituals and recording their stories, Williams adopted symbols which he would continue to incorporate into his work.

Aubrey Williams

Tribal Mark II

(1961)

Tate

Tribal Mark II (1961) reveals the extent of the Warrau’s influence and is characteristic of the painterly language Williams was exploring through the late 1950s and early 1960s. Central to the painting is a bone-like-glyph – a glyph is a carved or inscribed symbol often associated with indigenous languages – which appeared in many of the artist’s works during this period. Here, the glyph resembles an animal form, similar to fossils one might uncover in an archaeological dig. The repetition of the glyph in Williams’ work can be seen as linked to his preoccupation with what he described as ‘the human predicament, especially with regard to the Guyanese situation’, in other words the reality of living under British colonial rule, as well as the way his years with the Warrau tribe stayed with him. He particularly spoke of a ‘strange, very tense, slightly violent shape coming in somewhere. It has haunted me all my life and I don’t understand it; a subconscious thing coming out’. For Williams, the glyph was associated with an act of violence, particularly in relation to the colonisation of Guyana.

2. He refused to be pigeonholed as an Abstract Expressionist

Williams migrated to Britain in 1952, first Leicester, before settling more permanently in London in 1954 where Williams attended Saint Martins School of Art. Here he became better acquainted with the work of the Abstract Expressionists. As an active participant in the London art world, two exhibitions at Tate had a resounding impact on Williams, Modern Art in the United States (1956) and New American Painting (1959). It was here that Williams encountered the works of American Abstract Expressionists in the flesh; a movement Williams came to admire, even describing Jackson Pollock as ‘our God!’

Aubrey Williams

Death and the Conquistador

(1959)

Tate

Returning to Tribal Mask II, the impact of the Abstract Expressionists is clear. The presence of the glyphs in the painting are reminiscent of one of Williams’ earlier compositions, Death and the Conquistador (1959), which was inspired by Jackson Pollock’s paintings from the mid-1940s. Williams viewed his work as a response to the Abstract Expressionists, drawing from Franz Kline in addition to Pollock. The isolation of the glyphs in Tribal Mark II between two darker, emptier spaces, provides a direct contrast with the central intentional mark-making in a way that is reminiscent of Kline.

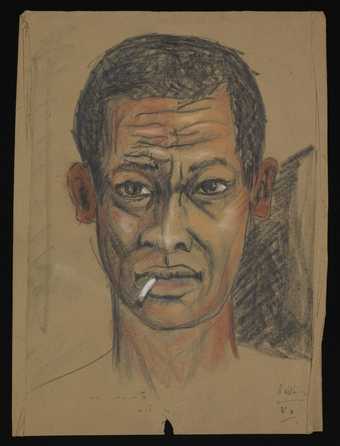

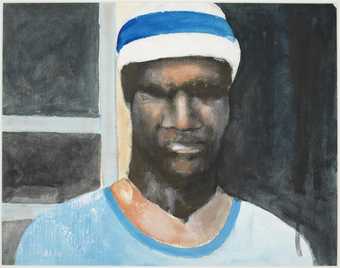

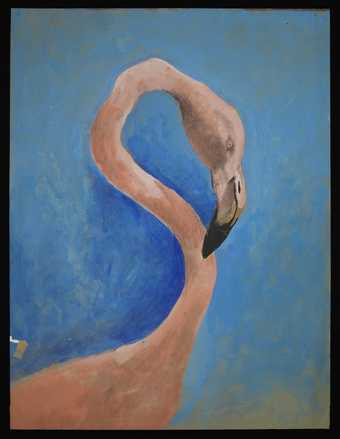

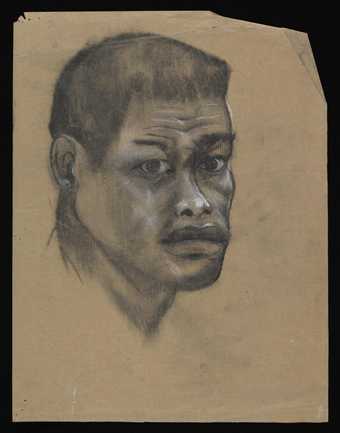

In 1981, Williams’ play between negative spaces of colour and sweeping gestures led to his display at the Commonwealth Institute of Art, which was at the forefront of promoting experimental abstract art in Britain, cementing his reputation as an Abstract Expressionist. Yet, looking into Williams’ archive reveals he continued to make figurative studies and representational work. Detailed and more simple portraits, life drawings of the female nude, studies of animals, birds and flowers from the early 1950s through to the early 1990s demonstrates Williams’ resistance to being pigeonholed by one movement. Rather, Williams’ preoccupation with Abstract Expressionism may have stemmed from a desire to communicate the visual culture of indigeneous peoples through modernist forms, as a process of decolonisation. Why not take a look at Williams’ archive for yourself to see what you can find?

Aubrey Williams

Painting of a flamingo

(1968)

Tate Archive

Aubrey Williams

Sketch portrait of a man

([1960s])

Tate Archive

3. He was one of the founders of the British Caribbean Arts Movement

Following the Second World War, there was a call to the Caribbean for people to migrate to Britain in order to help rebuild infrastructure and create a Welfare State. This happened under the British Nationality Act of 1948 which granted UK citizenship to those from Caribbean colonies. Now commonly known as the Windrush era, named after the ship Empire Windrush that brought over the first large group of people from the Caribbean in 1948, Aubrey Williams was among the Caribbean artists who settled in the UK during that time.

Prior to migration, political and cultural transformations in the Caribbean in the 1940s had already established grassroots independence movements which had an overwhelming impact on artists, including Williams. In fact, Williams was one of the members of the Working People’s Art Class (WPAC) which was established by Edward Rupert Burrowes to help people develop their art skills. This organising and creative expression laid an important foundation for Williams, alongside the artists Denis Williams and Donald Locke, prior to arriving in Britain.

The 1960s brought about an increase in activism, spurred by the rise of the Black Power and Black Civil Rights movements in the US, with similar organisations established in Britain such as The Race Today Collective and British Black Panther Party. Meanwhile, in London in 1966, artists and visual writers came together through activism for the first time with the establishment of the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) of which Aubrey Williams was a founding member. Alongside Ronald Moody, Althea McNish, Errol Lloyd, Paul Dash and Winston Branch. CAM’s focus was on an intellectual exchange of ideas with the purpose of creating a decolonised Caribbean aesthetic in the aftermath of Caribbean independence from the UK.

CAM was part of a wider Black Arts Movement, which gained further momentum during the 1980s. Among Williams’ activities was the organising of the forum ‘Seeking a black aesthetic’ in which a group of artists, writers and filmmakers who arrived in Britain in the 1950s were brought into dialogue with artists, writers and filmmakers born in Britain. In 1995, Denzil Forrester curated a number of exhibitions under the name ‘The Caribbean Connection’ focusing on key members of the Caribbean Artists Movement including Errol Lloyd, John La Rose, Ronald Moody, Aubrey Williams, Frank Bowling, Bill Ming and John Lyons.

4. Some of his paintings were inspired by Russian composer Shostakovich

Aubrey Williams

Shostakovitch 3rd Symphony Opus 20

(1981)

Tate

Dmitri Shostakovich was a twentieth-century Russian composer, who Williams first came across in his mid-teens, when he heard Shostakovich’s Symphony No.1. The composition stayed with him, with Williams noting how it made him discover ‘a sonic connection with a new wellspring of this state of human consciousness we call art’ and from the 1970s onwards while working between studios in Jamaica, Florida and London, he produced the ‘Shostakovich Series’ of 30 large-scale oil paintings dedicated to the symphonies. With bold, gestural strokes in vivid colours, Williams attempted to capture what he described as the ‘profound visual connotations’ and the way it made him ‘feel colour’.

Shostakovitch’s 3rd Symphony Opus 20 (1981) was painted in the period following Shostakovich’s death in 1975, when Williams found a renewed vigour for the subject. The broad gestural strokes in the centre of the frame, in various shades of red, surrounded by dark negative space at the edges of the image, recall the form of Williams’ earlier work Tribal Mask II. You can still seethe influence of the glyph-like figures that are a familiar characteristic for Williams. But with Shostakovitch 3rd Symphony Opus 20, Williams is much more generous and expressive in his use of colour, with the dark, negative space pushed further to the edges by washes of bright yellow and blue. By trying to translate the experience of Shostakovich’s symphonies to canvas, Williams marked a new period of experimentation.

5. Williams faced great adversity throughout his career

Despite Williams finding some early success upon migrating to Britain, including an exhibition at the New Vision Centre Gallery, Caribbean people were largely met with racist policies and actions. Though Caribbean people had been encouraged to migrate to help rebuild Britain, they were met with adversity. In 1958 the Notting Hill riots saw Black people terrorised in their own neighbourhood on successive nights and in 1968 Enoch Powell gave his infamous, racially explicit ‘rivers of blood’ speech. By the 1960s Parliament sought to end migration to Britain from the Commonwealth through a series of new immigration laws in 1962, 1968 and 1971. Within the Caribbean Arts movement, too often recognition proved marginal, and artists such as Williams were increasingly ignored by the art world. In fact, Williams was omitted from every major survey of British painting in his lifetime.

It was only after Williams’ death in 1990 that he started to gain critical acclaim, with his archive being acquired by Tate in 2001. When encountering Williams' work during the 1980s some people presumed it to be abstract and therefore non-political. However, re-reading Williams through a contemporary lens with increased knowledge about his connection to indigenous Guyanese cultures, we can see how Williams snuck resistance to Britain’s colonial rule into a modernist form, previously dominated by artists from the West.

Research supported by Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational in partnership with Hyundai Motor