When Wassily Kandinsky wrote to his New York gallerist Jerome Neumann in December 1935, he was clearly anxious to reassure him once again that he had painted his first abstract picture in 1911: ‘Indeed, it’s the world’s first ever abstract picture, because back then not one single painter was painting in an abstract style. A “historic painting”, in other words.’ Sadly, this historic painting was thought lost. The artist neglected to take it with him when he left Russia in 1921 for Germany, before later moving to France. He knew the art world was engaged in a contest. To be acknowledged as having produced the first abstract painting had become a highly coveted prize. Which modern artist could claim that prize was still being fought over. The other leading candidates were František Kupka, Robert Delaunay, Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich. What Kandinsky did not know is that a Swedish painter by the name of Hilma af Klint had created her first abstract painting in her Stockholm studio in 1906, five years before him. What’s more, she had taken the same path towards abstraction. Without knowing of each other’s existence, the two artists seem to have travelled for a long way like two trains on the same tracks. Klint arrived before Kandinsky.

The first abstract artist? (And it's not Kandinsky) Focus: Hilma Af Klint

Wassily Kandinsky is generally regarded as the pioneer of abstract art. However, a Swedish woman called Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) might claim that title

Who was Hilma af Klint? And how did she become an artist? Two aspects of her biography would give her an advantage. First, the admiral’s daughter was born in 1862 in Sweden, a country that permitted women to study art well before France, Germany or Italy. As a result, she was able to enrol at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm in 1882. After graduating five years later, she took the lease on a studio in the city’s artists’ quarter and gradually gained recognition as a landscape and portrait painter. She also had a passion for the study of plants and animals, and in 1900/1901 worked as a draughtswoman for the veterinary institute.

Secondly, Klint was born into a protestant family and came into early contact with theosophy. It doesn’t take a friend of the esoteric to see the advantages that theosophy could offer a young artist. In the nineteenth century no one doubted that great works depended on equally great inspiration. Hardly anyone, however, believed that when women painted, the higher powers came into play. Theosophy, founded by a woman (the Russian Helena Petrovna Blavatsky), viewed things differently. Women were welcomed as members and held senior positions. In short, it was the first religious organisation in Europe that did not discriminate against women. Klint was seventeen when she attended her first spiritualist seance.

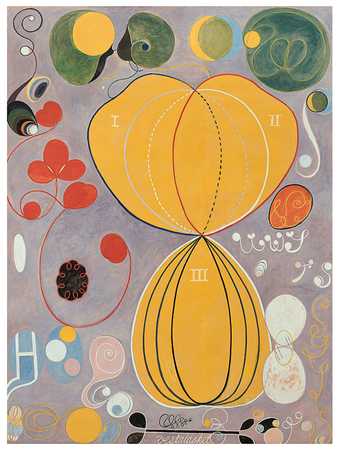

Hilma af Klint

The Ten Biggest, No 7 1907

Oil and tempera on paper

328 x 240 cm

In 1905 she noted that she had heard a voice that had given her the following message: ‘You are to proclaim a new philosophy of life and you yourself are to be a part of the new kingdom. Your labours will bear fruit.’ Between November 1906 and March 1907 she painted a series of abstracts, small-format canvases entitled Primordial Chaos. Some of them are reminiscent of landscapes, of a stormy sea above which flicker mysterious lights. Others break entirely free from representation, combining geometric shapes such as spirals with dynamic brushstrokes, letters of the alphabet and symbols. The mood is expressive and resembles that of the drawings she made apparently unconsciously during seances in the 1890s. The Surrealists were later to call this method ‘automatic drawing’.

The Primordial Chaos series was a seed from which almost 200 abstract paintings were to develop over the following years. Between August and December 1907 Klint created a series of monumental works entitled The Ten Biggest, characterised by ovals, circles and serpentine lines in radiant colours. The organic forms of the early abstractions gave way to a rigorous geometricism. In 1914/1915 she painted The Swan, composed of circular forms on a red ground. By the time of her death in 1944, the painter had shown none of her abstract works in any exhibition.

What led Klint to abstraction? An interest in invisible forces was widely accepted, rather than being limited to followers of the occult. By the end of the nineteenth century, the natural sciences had already discovered many invisible forces, including infrared light, X-rays and electromagnetic fields. These phenomena presented the arts as well as science with new questions: was it possible to paint not only organisms, but vital forces as well? Not just an orchestra, but music too? What forces, rays or oscillations were yet to be discovered? Like Kandinsky, Klint was probably familiar with the attempts of theosophical authors Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater to translate music into visual forms. A book illustration of 1902, depicting red zigzag lines and black circles, was entitled Explosive Anger; another, dating from 1905 and presenting a colourful explosion of form, was called the Music of Gounod. One of the most successful theosophical texts was published in 1904/1905. It had been written by Rudolf Steiner, whom Kandinsky and Klint met, independently of one another, in 1908. Its title was: How to Know Higher Worlds. Klint and Kandinsky painted the answer: through art.

Hilma af Klint

The Swan, No 17, Group IX, Series SUW 1914-1915

Oil on canvas

155 x 152 cm

The importance that abstraction would assume in the history of art become clear only at a later date. In 1936 an exhibition opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York entitled Cubism and Abstract Art. In a diagram drawn by Alfred H Barr for the catalogue cover, the history of art culminates in, and ends with, abstract art. Today this view seems too one-sided. We relish the diversity of twentieth-century art, whether representational or abstract. We value abstract art, however, as a freedom of expression that we would not want to live without. And Hilma af Klint discovered it back in 1906.

See at Hilma af Klint and Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life Tate Modern, 20 April – 3 September 2023

See also

-

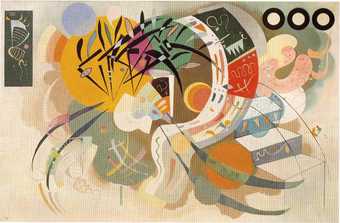

Kandinsky: The path to abstraction

Kandinsky: The path to abstraction; past exhibition at Tate Modern

-

Between Text and Image in Kandinsky’s Oeuvre: A Consideration of the Album Sounds

Focusing on the album of poetry and woodcuts called Sounds (Klänge), published c.1912, this paper examines how Kandinsky understood and exploited the relationship between text and image. It shows how he conceived of the album as an example of synthetic art and explores the broader principles underlying his idea of artistic synthesis.

-

Kandinsky and Contemporary Painting

The author assesses the reach of Kandinsky’s early painting, first reflecting upon the sense of scale and time in Kandinsky’s art, then his clash with the Constructivists and his emergence in New York in the 1940s as a ‘painterly’ European artist of significance. The paper finally dwells upon the nature of complexity in today’s painting, and its connections with Kandinsky across a century of change.

-

Lost Art: Wassily Kandinsky

The Gallery of Lost Art is an immersive, online exhibition that tells the fascinating stories of artworks that have disappeared. Each week a new story of loss is added, and the evidence presented for examination

-

Paintings by Kandinsky from the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum

Paintings by Kandinsky from the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum: past Tate Britain exhibition

-

Mondrian and his Studios

Mondrian and his Studios, is a new exhibition opening 6 June at Tate Liverpool exploring the artist's relationship with architecture and urbanism