Kandinsky’s work was first seen in Britain at the Allied Artists’ Association’s second London Salon, held at the Royal Albert Hall in 1909. In an exhibition that consisted of more than 1,000 works, primarily by British artists, he exhibited two paintings, Jaune et Rose and Winter Landscape (both 1909; the latter is now in the collection of the Hermitage), plus twelve woodcuts. Frank Rutter, art critic of the Sunday Times and director of the Leeds City Art Gallery, was keen to play a more active role in the British art scene and the previous year helped to establish the AAA with 40 other founder members, including Walter Sickert, Walter Bayes and Spencer Gore. How Kandinsky was introduced to the show is uncertain, but it may have been the contact with one member of the committee – a Russian called Princess Marie Tenicheff, who had co-organised an exhibition of art from her home country.

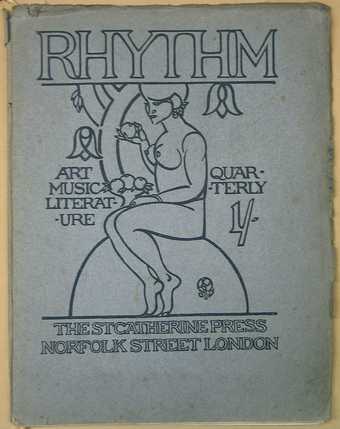

Among those who quickly became interested in Kandinsky were Rutter’s Leeds friends Michael Sadler and his son, also called Michael (the latter changed his surname to Sadleir to avoid confusion). They were actively interested in art – the father as a collector and the son, a recent Oxford University graduate, as a writer for a new art magazine, Rhythm.

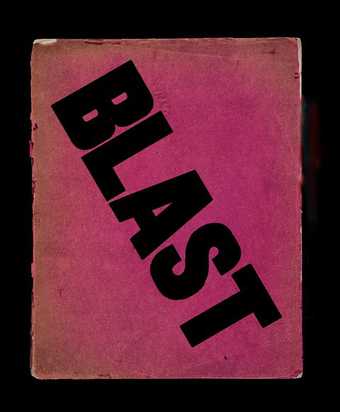

Percy Wyndham Lewis

Cover of Blast, no.1, 1914

Courtesy The Poetry Collection, State University of New York at Buffalo

© Wyndham Lewis and the estate of Mrs G.A. Wyndham Lewis by kind permission of the Wyndham Lewis Memorial Trust

Cover of Rhythm 1912 co-funded by Michael Sadler and to which his son contributed

© Courtesy Tate archive

Kandinsky would show his work in the following AAA exhibitions, and at the 1911 event Sadleir confirmed his interest by buying four of his woodcuts. This prompted him to write to the artist, in what was the start of an important correspondence (now held in the Tate archive) that would ultimately lead to Concerning the Spiritual in Art being published in English. On 2 October 1911 Sadleir wrote firstly to say how delighted he was to purchase the woodcuts and then “to ask whether you would mind if I reproduce one of them in my quarterly journal Rhythm”. The magazine had been set up (with a £50 donation from Sadler) earlier that year by Sadleir’s university friend, the editor and critic John Middleton Murry, who galvanised a group of writers and artists – including Anne Estelle Rice, as well as the Scottish colourists J.D. Fergusson and S.J. Peploe. On 6 October 1911 Kandinsky replied:

Thank you for sending me your periodical. I am very glad to give permission for the reproduction of my woodcut. I am very pleased that the so-called modern art movement is mirrored in your journal and meets with interest in England. Mr [Rupert] Brooke from Cambridge also told me about this last winter. I enclose for you the prospectus of the art periodical that I have founded; the first issue is due to appear in January. Also this month my book Über das Geistige in der Kunst [Concerning the Spiritual in Art] will be published.

Sadleir was able to introduce Kandinsky’s ideas from this book in Rhythm, mentioning them in English for the first time, several months before Alfred Stieglitz published extracts in Camera Work in July 1912. In his article “After Gauguin” that appeared in the early months of 1912, Sadleir wrote:

From this book two main contentions arise.The first is virtually a statement of Pantheism, that there exists a ‘something’ behind externals common to nature and humanity alike.That is what Wordsworth believed, but while he approached the question subjectively, contenting himself with describing the experiences of his mood communion with the nature around him, the new art is to act as an intermediary for others, to harmonise the inner Klang [resonance] of external nature with that of humanity, it being the artist’s task to divine and elicit the common essentials underlying both.The second contention follows naturally from the first. An art intent on expressing the inner soul of persons and things will inevitably stray from the outer conventions of form and colour.That is to say, it will be definitely unnaturalistic, anti-materialist.

Spencer Gore

The Beanfield, Letchworth

(1912)

Tate

After their initial exchange of letters, Kandinsky and Sadleir didn’t correspond for eight months. It was in the late summer of 1912 when Sadler proposed to his son that they should visit the artist that Sadleir wrote asking if they could meet. Kandinsky replied, inviting them to visit him and his partner Gabrielle Münter at their country cottage near Murnau, a small town about 35 miles south of Munich. On 16 August 1912 they spent an enjoyable day, by Sadler’s account, engaging in animated conversation. In a letter to his wife the day after, he describes the interior of the cottage and a little of Kandinsky’s predilections:

Everything was very simple. On the walls were small pictures on glass, very brightly coloured, of religious subjects mostly - some eighteenth-century Bavarian peasant work, some painted by a man in Murnau, the latter practices the old traditional art, a few (mystic and primitive-looking) by Kandinsky himself. For Chinese art & character he has a deep respect & admiration. He was inclined (though not at all obtrusively) to talk about religious things, & is much interested in mystical books & the lives of the saints. He has had strange experiences of healing by faith.

The trip cemented Kandinsky’s friendship with the Sadlers. Among the first to buy his work in Britain, Sadler would proudly show his Kandinskys – including Fragment II for Composition VII 1913 – to guests who visited his home in Leeds, including the then director of the National Portrait Gallery and editor of The Burlington Magazine C.J. Holmes and the writer John Galsworthy. Father and son’s admiration for his work was greatly appreciated by the painter, and within a month Sadleir secured the translation rights for Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

It was only a matter of time before the more perceptive of British painters began to incorporate motifs and colour cadences in their own work. One of the lesser documented artists was Spencer Gore, an exhibitor in Roger Fry’s influential Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition. During the late summer and autumn of 1912 he produced more than twenty canvases in Harold Gilman’s house in the newly built Letchworth Garden City. Paintings such as The Beanfield, Letchworth 1912, with its thick striated bands of bright colour, suggest a debt to Kandinsky. (It is known that Gore had developed his own colour chart by this time.) A friend of Gore who directly acknowledged an influence was C.R.W. Nevinson, who may well have seen his pictures while studying in Paris (he had a lot of Russian friends and acquired the nickname Nevinski). On his return to England, he declared a radical shift in his work, saying that he “was dissatisfied with representational painting. Like many others I was attracted by abstract art, and the colour harmonies of Kandinsky”.

When the full English version of Concerning the Spiritual in Art appeared in April 1914, it was well received, and Kandinsky was pleased with the result. In a letter to Sadleir, he wrote: “It is a constant joy to me to know [that there are] such friends of my art in distant England as yourself and your father.” Among the avant-garde artists who quickly took it up were Wyndham Lewis and Edward Wadsworth (both of whom would have come across Kandinsky’s work when studying in Munich in c.1906). In the first issue of Lewis’s hard-hitting Vorticist manifesto journal Blast (1914), he featured a review by Wadsworth of the book. It sat next to an image of Wadsworth’s painting Radiation 1913 which, according to his daughter Barbara, was “strongly influenced by the Kandinsky essay”. In his review he wrote:

This book is a most important contribution to the psychology of modern art. The author’s eminence as an artist adds considerable value to the work - fine artists as a rule being extremely reluctant to, or incapable of, expressing their ideas in more than one medium. Herr Kandinsky, however, is a psychologist and a metaphysician of rare intuition and inspired enthusiasm.

For Lewis, it was Kandinsky’s woodcuts and his “original and bitter” use of colour combinations that ranked him above other avant-garde artists. Lewis particularly appreciated his ideas about discordant colour harmonies suiting a more tumultuous epoch. There was also a close association at this time with Kandinsky’s spiritual evolutionism, evidenced in Lewis’s interest in Feng Shui and the statement in Blast that “in a painting certain forms MUST be SO”.

While most of these artists moved on to different ends – Nevinson would launch the Futurist manifesto with Marinetti several months later – the most specific, enduring, yet least known influence of Kandinsky on British artists at that time was on James Wood. He had absorbed the lessons on colour theory, particularly those establishing correspondences between colour and musical tones, when studying at Percyval Tudor-Hart’s art school in Paris in 1909, along with the Americans Morgan Russell and Stanton Macdonald-Wright (who would go on to formulate Synchronism in the States), and then again in Tudor-Hart’s London school several years later. As the co-author of The Foundations of Aesthetics with C.K. Ogden and I.A. Richards (not published until 1922), Wood wrote on the experience and enjoyment of art, incorporating the concept of synaesthesia and defining its expression in the visual arena as an awareness “of certain shapes and colours. These when more closely studied usually reveal themselves as in three dimensions, or as artists say, in forms”, and by studying these forms, impulses are “aroused and sustained, which gradually increase in variety and degree of systematisation”. Like Kandinsky, Wood and his co-authors assigned emotions to colour effects:

To these systems in their early stages will correspond the emotions such as joy, horror, melancholy, anger and mirth; or attitudes such as love, veneration, sentimentality.

Kandinsky believed that the psychological effects of colours were, in fact, the vibrations of the soul, and Wood and his co-authors subscribed to a similar view:

In the interpretation of works of art at an early stage, if we allow ourselves to take on the appropriate mood, we may come into contact with the personality of the artist. [and that the choices that comprise an artwork seem] to be the only way, unless by telepathy, of coming into contact with other minds than our own.

These views were mirrored in Wood’s own paintings, where the colour correspondences serve specific functions and where the image vibrates and resonates beyond the canvas.

Although British painters at this time drew upon the theories and teachings of avant-garde artists on the continent, for many it was a mere dalliance. One feels – when looking back to the work of artists associated with the Bloomsbury circle, the Vorticists and others – that if only they had persevered in exploring the avant-garde, the future direction of British art may have dramatically shifted. It is worth noting that many of these artists, with the notable exception of Wood, returned to a more conservative and representational mode of painting later in their careers.