The panel discussion ‘Blackness in Contemporary African Art Practice’ was convened and moderated by Portia Malatjie, Adjunct Curator of Africa and African Diaspora at Tate, and included presentations by Nomusa Makhubu, Associate Professor in Art History at the University of Cape Town, Suzana Sousa, an independent curator and writer, and Minna Salami, an author, feminist theorist and lecturer.

Clockwise from top left: Portia Malatjie, Suzana Sousa, Nomusa Makhubu and Minna Salami during the panel discussion ‘Blackness in Contemporary African Art Practice’

The panelists reflected on the different modalities through which Blackness is constituted. What became clear from each presentation is that Blackness does not have a singular meaning. Instead, it is marked by different frequencies that find resonance in a myriad of contexts. While Makhubu and Sousa offered rigorous analyses through case studies in contemporary African art practices, Salami offered a lyrical and future-centric idea of what Blackness could be.

Historically, ‘Black’ has functioned as an organising category among communities with very different cultures and traditions, particularly within histories of oppression and violence that continuously necessitate a politics of resistance. This classification is useful insofar as it allows for a common language. However, it can also be harmful – any attempt at a fixed definition and containment of what Blackness is, however positive, runs the risk of perpetuating the epistemic violence originally inflicted by colonialism and slavery. It is crucial to complicate our understanding of what Blackness is by addressing the conditions that created Blackness in the first place. This is clearly articulated by Afropessimism author R.L. in their article ‘Wanderings of the Slave: Black Life and Social Death’:

the violence of anti-blackness produces black existence; there is no prior positive blackness that could be potentially appropriated. Black existence is simultaneously produced and negated by racial domination, both as presupposition and consequence. Affirmation of blackness proves to be impossible without simultaneously affirming the violence that structures black subjectivity itself.1

Often, literary and academic theorisations of Blackness that originate in the West (particularly, the USA), and in some cases the Caribbean, seem to gain popularity and priority over work by African scholars.2 In the context of the panel discussion, it was invigorating to listen to articulations of Blackness from an Africa-centric and Black feminist perspective. By merging African and diasporic experiences, the panelists highlighted, and wrestled with, what author Panashe Chigumadzi refers to as the suture between Africa and the Afro-diaspora. Chigumadzi notes: ‘This suture creates reverberating chambers where we are continually Blackened by each other’s sufferings. Just as all of us were Blackened by the Transatlantic slave trade, we were blackened again by the Scramble for Africa and with it, Germany’s Herero and Nama Holocaust.’3

Kudzanai Chiurai

Genesis [Je n’isi isi] VII 2016

Photograph

1200 x 1800 mm

Goodman Gallery

© Kudzanai Chiurai

The title of Makhubu’s presentation, ‘I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance: Reflections on Recurrence and Resistance in Contemporary Art’, began with a quote from American abolitionist Sojourner Truth. In doing so, Makhubu highlighted Sojourner’s awareness of the consumption that is inextricably linked to the production and display of images of Black life. The famous image of her in a photographer’s studio, her knitting in hand and her eyes squarely placed on the lens, was made into a sellable postcard (c.1864) through which she raised money to support her abolitionist work. Similarly, Makhubu suggests that the politics of contemporary photography are entangled with market forces and operate as a currency through the recurrence, repetition, circulation and exchange of images. Just as currencies gain or lose value over time, the value of images is negotiated based on the shared belief of the symbolic value of what is being represented. Pointing to the appropriation of images of violence (in particular to apartheid), she raised the critical question of whether it is possible to escape the confining circulation of colonial and apartheid images. To this point, Makhubu discussed works of young contemporary artists such as Kudzanai Chiurai, whose series Genesis [Je n’isi isi] 2016 incorporates colonial imagery and Christian iconography. In the context of South Africa, such images are typically consumed through the largely white-owned gallery system by majority white collectors. As such, Makhubu asks whether a move away from the use of such images would enable the creative arts to explore more profound political articulations of historical trauma.

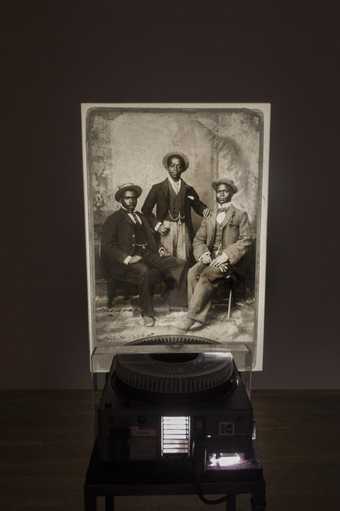

Santu Mofokeng

The Black Photo Album / Look at Me 1997

Slide, 35 mm, 80 slides, projection, black and white

Duration: 6min, 40sec

Tate

© Santu Mofokeng, courtesy Maker, Johannesburg

To return to Makhubu’s title, the evocation of the ‘shadow’ provides an entry point into reflecting on what images mean to Black people in the context of South Africa. For example, for South African photographer Santu Mofokeng, the notion of the shadow features prominently. For Mofokeng, the shadow revealed a more complex reading of how images are encoded and decoded within the Black community. Believed to contain a person’s essence, photographs are considered to embody what Ugandan poet Richard Carl Ntiru refers to as ‘the prescient perception of the inner idea of life’.4 A person’s image cannot be separated from their shadow – read as aura, presence, dignity, spirit, or what essayist Simon Njami refers to as ‘the starting point of an ontological quest, one that we do not know where it will lead’.5 This is critical in the context of a long history of photography as a tool to dehumanise the Black body.6 Artists such as Santu Mofokeng made works that insisted on the dignity and agency of Black people, both during and after apartheid.

Ana Silva

Caminhada #3 2020

Plastic woven bag, cotton string

170 x 1740 x 100 mm

insofar Art

© Ana Silva

Reinata Sadimba

Untitled 2020

190 x 280 x 120 mm

Graphite on ceramic

AKKA Project

© Reinata Sadimba

In the second presentation, Suzana Souza explored the artistic practices of Reinata Sadimba from Mozambique and Ana Silva from Angola. She reflected on the construction of race and identity in Southern Africa, acknowledging the impact of place, culture and language in the making of subjectivities. Souza demonstrated that conceptions of Blackness are not always entirely focused on racial identity. She explained that in Angola and Mozambique, race is entangled with class and privilege forged during the colonial period and identities are shaped by the recent memories of the liberation struggle. Indeed, Sousa quoted Silva as saying: ‘I cannot separate this fact from my experience in Angola, at a time when scarcity and access to art materials appeared. Colonial war, the civil war marked the pace. Creativity was taken by exploration around me, of what existed. That experience had a great impact on my work and in my life.’ Sousa’s presentation highlighted the manner in which factors outside of race are significant in specific geographies. For Sadimba, her experiences of working as an artist in Mozambique were informed by her ethnicity, demonstrated through her insistence on speaking her dialect of Makonde as a mode of resistance, even to people who do not speak the language.

In the last presentation, Salami considered temporality within Blackness, exploring the roles and responsibilities of the Black artist towards time and towards the creation of new worlds. By proposing Blackness as a conduit that connects ancient and contemporary African knowledge systems in the continent and the diaspora, she explored the possibility of what Blackness can be. In particular, she described the possibility of ‘an existence that isn’t defined by the pain of white supremacy’. Salami read Blackness as a ‘radical humanist intention that expands global consciousness, bringing all of humanity toward a higher ethical and a more imaginative space-time’ through an understanding of cognisance which she defined as a means of coming to awareness. She noted, ‘In the context of Blackness, I am referring to this formal meaning but also to the evocations of the word that sits somewhere between intuition, intellectual knowledge and lived experience’. She further elaborated that cognisance is situatedness and thus conveys a Blackness that is equally shaped by struggle as by an existence that is not about the pain of white supremacy. Inspired by author Toni Morrison’s quotation ‘Black women have always considered themselves superior to white women. Not racially superior, just superior in terms of their ability to function healthily in the world’, Salami pointed to the particular strengths of Black women in navigating the world. In this sense, Blackness is read through a Black feminist knowledge that synthesises both the political and the aesthetic. It is not only political but psychosocial, emotional, cultural, spiritual, relational, experiential and interior.

The discussion was illuminating and inspiring. I would, however, have liked to hear about the disruptive capacity that Blackness holds – thinking through, for instance, the consequences of Black rage and Black anger in light of persistent histories of oppression. Within the context of pervasive anti-Blackness, a focus on Black rage would in fact challenge the demands on Blackness to align itself with respectability through the erasure of anger from discourses about race. Black rage contributes to the conditions of possibility to imagine otherwise (as seen in global BLM protests, the #feesmustfall and #rhodesmustfall movements, and protests following the killing of George Floyd in the US). Injustices are unfair but they are also enraging. How can we begin to think about Blackness that accounts for our sense of anger, and thus, our subjectivity? And how do we begin to think of Black rage as a modality that can contribute to the work of liberation? Black rage as insurrection and as refusal. Feminist theorist, author and co-founder of Practicing Refusal Collective Tina Campt reads refusal as not simply an act of opposition or resistance, but a fundamental renunciation of terms of impossibility defining certain subjects.7 Read through this lens, Black rage presents a possibility of renouncing the terms of anti-Blackness.

It might seem as though there is increased awareness about and attention to Blackness – this could not be further from the truth. Black people have historically spoken out about their subjectivity and the conditions that affect their experiences. The difference is visibility (maybe even hypervisibility) within art institutions. This raises the question of responsibility in ensuring that these critical conversations are handled with care and that they allow us to continue to navigate refusals and resistances against the dehumanisation of the Black body. In this regard, Makhubu, Sousa and Salami’s reflections provide a model of how to consider Blackness in contemporary African art practice with care.

Nkgopoleng Moloi is an independent writer, curator and photographer.

To access a recording of this event, please contact htrc.transnational@tate.org.uk.