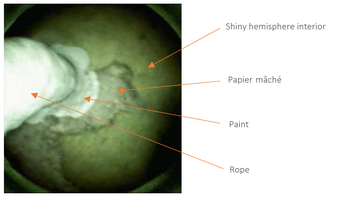

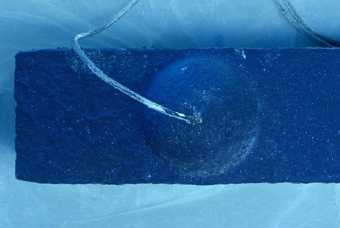

Fig.1

Eva Hesse

Addendum 1967, photographed after the completion of the 2017–18 conservation treatment

Papier mâché, wood and cord

124 × 3029 × 206 mm

Tate

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

During her short career as an artist, from her graduation from art school in 1959 to her death in 1970, Eva Hesse explored and experimented with diverse and novel materials and techniques.1 Her ambitious sculptures, which are often grand in scale, have left a legacy of challenges for those working to preserve them. One such sculpture is Addendum 1967 (fig.1), a large structure consisting of a narrow panel of wood that is positioned horizontally on the wall at a height of just over two metres from the gallery floor. On the face of the panel are seventeen hemispheres spaced out at increasing intervals from left to right. These hemispheres are made from papier mâché, and the wood has been coated with the same material. Cotton rope cords of around three metres in length descend from the centre of each hemisphere and coil onto the gallery floor. The sculpture as a whole has been painted grey using acrylic copolymer emulsion and coated with clear polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) polymer. The ropes alone have an additional coating of a clear (unpigmented) acrylic copolymer emulsion.

For many years Addendum posed a particular challenge regarding how to remove a significant amount of accumulated soiling from the artwork surface without causing unwanted change to the underlying materials. This soiling was the natural result of the extensive display of Addendum, both at Tate and internationally, since acquisition by the museum in 1979. In some areas, the soiling had become partly embedded into the paint and coating layers, resulting in a visually disturbing, uneven tonality across the work. The softer emulsion coating on the ropes, and the fact that the lower portions of the ropes are intentionally displayed in contact with the gallery floor, served to emphasise this unevenness further. There was also a slight yellowing resulting from the soiling layer and ageing of the rope coatings, which further distinguished them from the papier mâché section. This visual inconsistency compromised the uniformity of the work, which is critical to its appearance and meaning.

Extensive research has been carried out into the conservation of Hesse’s works in latex and fibreglass, including exploring ethical options for conserving these often seriously compromised sculptures. The material degradation of her latex, rubber and fibreglass artworks has rendered many unable to be exhibited or with a distinctly changed appearance.2 The condition of Hesse’s sculptures, how to approach their display, and when to conserve or even remake them3 have all been contentious topics, with key figures from Hesse’s life, her artistic practice and the wider art community endeavouring to glean her intentions for her legacy,4 including her views on the degradation and physical changes to the materials she was so passionate about.5 However, there has been relatively little focus on her earlier papier mâché sculptures, such as Addendum, which were made at a critical juncture in her practice when she began to use more ephemeral materials.6

Earlier explorations of Addendum had shown that the outer soft acrylic emulsion coating applied to the ropes was particularly vulnerable to cleaning treatment.7 In 2017–18 Addendum was put forward as a case study candidate as part of the NANORESTART (Nanomaterials for the Restoration of Works of Art) project, which aimed to develop and evaluate novel cleaning materials (broadly based on nanotechnologies) for modern and contemporary art.8 The research for this case study began in July 2017 and treatment took place between March and May 2018. While a detailed account of the treatment approach, evaluation of the novel materials, treatment decision-making process and outcomes for this sculpture has been published elsewhere,9 this paper presents the insights into the construction and materials gained when closely examining Addendum as part of NANORESTART. This includes exploring whether the surface coating could have been artist-applied, which is new information that in turn informed discussions as to whether the outermost coating needed to be preserved as part of the recent conservation treatment. As well as outlining the knowledge gained about Hesse’s material choices for Addendum, this article examines Hesse’s techniques and influences, using archival research and secondary literature on Hesse’s practice to show how this sculpture straddles a key transition point in Hesse’s use of materials.

Hesse’s serial art

Hesse fabricated Addendum for an exhibition titled Art in Series, which was held at the Finch College Museum of Art in Manhattan in 1967.10 The exhibition, organised by the artist Mel Bochner, explored the idea of seriality that many artists, including Bochner himself, were addressing in their work.11 As well as Hesse, Art in Series featured works by Sol LeWitt, Dan Flavin, Jasper Johns and Donald Judd.12 Hesse had been experimenting with seriality and repetition, as seen in a series of drawings produced at that time, as well as for sculptures such as One More Than One 1967 and Ditto 1967 (both in private collections), which feature repetitive circular forms.13 Her notebooks also demonstrate her views on this subject and remain an invaluable source of knowledge pertaining to her working practices and choice of materials.14

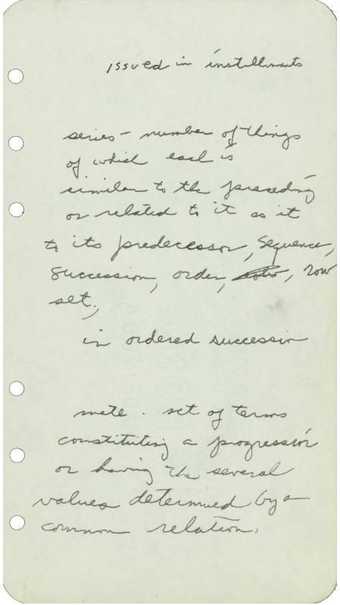

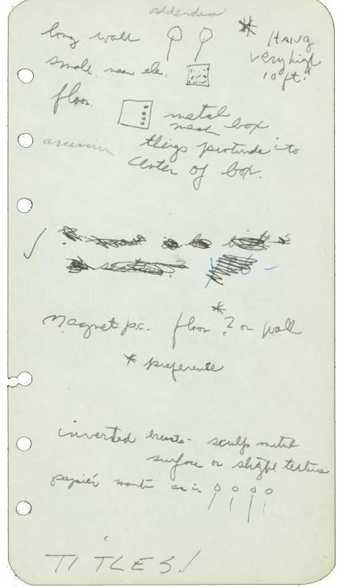

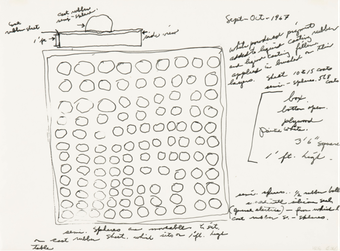

Fig.2a

Notes and sketches from Eva Hesse’s notebook, 1967–8

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

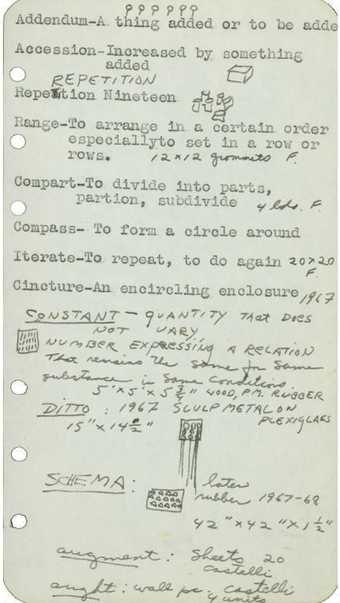

Fig.2b

Notes and sketches from Eva Hesse’s notebook, 1967–8

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

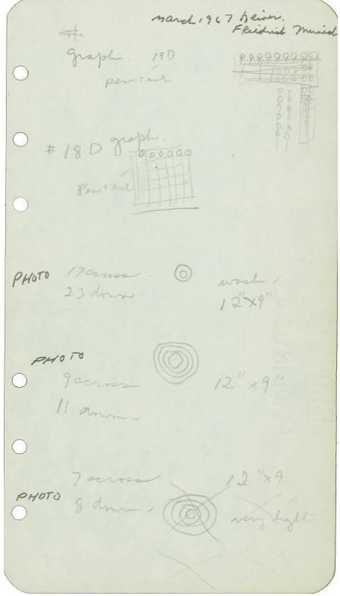

In her notebook for 1967–8 Hesse writes, ‘series – number of things of which each is similar to the preceding or related to it as it [is] to its predecessor, sequence, succession, order, row, set, in ordered succession’ (figs.2a and 2b). In the same notebook, Hesse also lists a range of titles based on these ideas, many of which were eventually used for other sculptures, such as Repetition 19 III 1968 (Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Schema 1967 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia). Around this time, Bochner gave Hesse a thesaurus, which became an inspirational tool for devising her artwork titles (fig.2b).15 Alongside the ideas and definitions seen in her notebooks, she also included sketches of works. Some of the first sketches for Addendum depict a simplified series of circles with descending lines (figs.3a and 3b).

Fig.3a

Notes and sketches from Eva Hesse’s notebook, 1967–8

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

Fig.3b

Notes and sketches from Eva Hesse’s notebook, 1967–8

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

In subsequent drawings the structure develops, and the series of hemispheres mounted in a rectangle or square appears, which then evolves into other sculptures around the same theme. For example, in her diary from summer 1966 Hesse drew a similar work to Addendum – most likely a sketch for either Ishtar 1965 (private collection) or Ennead 1966 (Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston)16 – that helps us to understand her ideas on sequence, series and the realisation of these sketches into works of art (fig.4).

Fig.4

Sketches from Eva Hesse’s diary, summer 1966

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

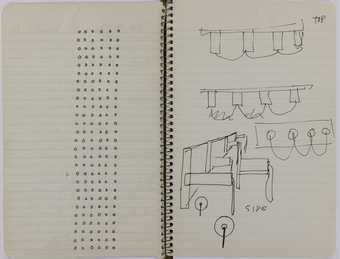

Addendum: A full-scale drawing

In addition to these sketches, Hesse made a full-scale drawing of Addendum (figs.5a and 5b), which was likely to have been used as a template when she came to create the sculpture. This previously unpublished drawing forms part of the LeWitt Collection in Chester, Connecticut and contains detailed measurements and calculations reflecting the intervals, hemisphere diameters and overall dimensions of the work. On the back of Addendum, vertical pencil marks can be seen indicating where supports should go (figs.6a and 6b), which mirror the markings for supports on the full-scale drawing. These highlight the technical aspect of the drawing produced in order to build the sculpture.

Fig.5a

Eva Hesse

Full-scale drawing for Addendum 1967

LeWitt Collection, Chester, Connecticut

© Courtesy the LeWitt Collection

Fig.6a

Eva Hesse

Detail of pencil markings on the back of Addendum indicating the position of the supports

Photo © Tate

Fig.6b

Eva Hesse

Detail of pencil markings on the back of Addendum indicating the position of the supports

Photo © Tate

In her statement for the Art in Series exhibition, Hesse discussed the unity of Addendum with regard to its surface texture and repetition:

The cord is flexible. It is ten feet long, hanging loosely but in parallel lines. The cord opposes the regularity. When it reaches the floor it curls and sits irregularly. The juxtaposition and actual connecting cord realizes the contradiction of the rational series of semi-spheres and irrational flow of lines on the floor. Series, serial, serial art, is another way of repeating absurdity.17

The monumental scale of Addendum marked a change in Hesse’s sculptural practice at this time. The sculpture is over three metres in length and two metres in height, and dominates the wall when displayed, with the ropes extending onto the floor. However, Ditto and One More Than One, both of which were also made in 1967, are smaller, with the former measuring 178 x 386 x 3 mm and the latter 216 x 381 x 140 mm. Hesse’s sculptures would continue to grow in scale from Addendum onwards, often encompassing several walls and extending from floor to ceiling, as seen in works such as No Title 1969–70 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York).18

Provenance

Addendum was acquired by Tate in 1979 from art collector Victor Ganz, who had purchased the sculpture in 1972 from Fourcade, Droll Gallery in New York. It was one of nine major works by Hesse that Ganz bought from the gallery that year; he had also purchased three of Hesse’s sculptures while she was still alive.19 It is unclear where Addendum was located between its fabrication and subsequent acquisition by Fourcade, Droll. It may have stayed in Hesse’s studio for several months, or longer. Shortly after Hesse’s death in May 1970,20 the dealer Donald Droll – co-founder of Fourcade, Droll and a friend of the artist – was given access to her estate,21 which was managed by Hesse’s sister Helen Charash, who made the sale to Ganz.

The funds from the sale to Ganz went on to finance the publication of critic and curator Lucy Lippard’s comprehensive publication on Hesse.22 The Director of Tate at that time, Norman Reid, was aware of the need to acquire works by Hesse; he had received a letter from British sculptor Barry Flanagan in May 1971 conveying that it would be a ‘splendid thing for Britain if the Tate Gallery were to acquire an example of her work’.23 Interestingly, Reid was aware of the challenges of acquiring (rubber) latex and referred to the material in a note of 1974 as ‘self-consuming, so ineligible for a permanent collection’.24 He recommended an acquisition be made of a work by Hesse that comprised more stable materials, perhaps leading to the choice of Addendum and Tomorrow’s Apples (5 in White) 1965, which were both purchased by Tate in 1979.

Development and use of papier mâché

Hesse began exploring papier mâché in 1964 while on a residency in Kettwig an der Ruhr, Germany, with her husband, the sculptor Tom Doyle. She found cast-off material in the factory they were using as a studio space, and started using cords, string and tubes as well as papier mâché to create simple shapes.25 Papier mâché is the traditional method of dipping strips of newsprint in glue and layering them to form shapes that have a hard structure once dry. Doyle recalls Hesse ‘messing around with papier mâché’ at this time, noting that:

It really suited her, her whole image. The reliefs started out sort of landscapey and complex. The first ones were more like painting, less jumping off the surface, more building up. Right away though she got much more adventurous about the whole thing and got into the wire and then filling them up with rope. You could date them by the way the colour became less and less important.26

Fig.7

Eva Hesse in her studio in The Bowery, New York, 1965

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Hesse was using papier mâché extensively in 1965–7, as shown in an image of her studio taken in 1965 (fig.7). This snapshot provides insight into her techniques, working practice and materials. Hanging on strings to Hesse’s right are most likely the unpainted forms of Untitled (Estate Balloons) 1966 (private collection), and on the table are additional papier mâché objects where the layering of traditional newsprint over a balloon form can be seen. Also visible on the table are cans of nu-HUE enamel spray paint in black, which is the surface finish used for many of her works during this period, including Untitled (Estate Balloons). There is also a label from a Liquitex product, and other Liquitex items such as acrylic gloss medium and varnish have been identified in other photographs of Hesse’s studio from this period.27

The top section of Addendum is a softwood batten structure that measures 3023 mm x 127 mm x 152 mm. The work features a series of seventeen hemispheres, spaced at increasing intervals in the following progression in inches: 1/8 of an inch, 3/8 of an inch, 5/8, 7/8, 1 1/8, 1 3/8, and so on. This is where the serial element of the work lies, with a numerical system that is used to determine the spacing between the hemispheres and to impart their specific aesthetic effect. According to curator Scott Rothkopf, after making the sculpture Hesse ‘retreated from this brand of mathematically predetermined seriality, rendering Addendum not only her greatest statement in this mode, but her last’.28

Fig.8

Eva Hesse

Detail of the upper part of Addendum showing finger depressions in the papier mâché

Photo © Tate

At this stage, Hesse was also modifying her papier mâché technique, moving from a homemade paste to a commercially available papier mâché mix.29 In Addendum, for example, she used a papier mâché pulp, rather than the more traditional strips of newsprint she was using previously (see fig.7). The pulp appears to have been applied directly onto the underlying wooden structure, after which she used her hands to manipulate it and create texture, such that visible imprints of Hesse’s fingers are embedded into the surface (fig.8).

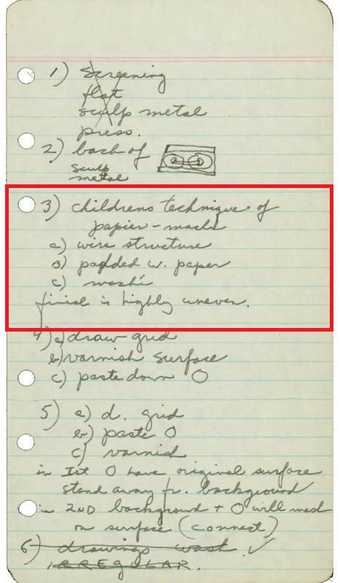

Fig.9

Notes and sketches from Eva Hesse’s notebook, 1967–8

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

In her notebook for 1967–8 Hesse refers to papier mâché as a ‘childrens [sic] technique’ and indicates that the resulting finish was highly uneven (fig.9). This may be a reference to the texture achieved through using papier mâché pulp, in contrast with the relatively smooth finish that results from the use of newspaper strips. After this point, Hesse moved away from papier mâché and towards what Lippard termed the ‘real’ materials used by many of her fellow artists: in Hesse’s case, this material was latex.30

A transition to new materials

Fig.10

Eva Hesse

Photograph taken with an endoscope of the inside of one of Addendum’s hemispheres, showing its shiny interior, the rope that is fed through it, and excess papier mâché and paint that have spilled through the rope’s hole and into the hemisphere’s cavity

Photo © Tate

Addendum is one of Hesse’s last works in painted papier mâché, and by the end of 1967 she was experimenting extensively with rubber latex, making test pieces to explore different application techniques.31 The domes in Addendum are significant in this regard as they reflect the development of a technique Hesse later used for her works in latex. To create the domes, Hesse is likely to have used a hard rubber ball cut in half, which was secured to the structure and used as a mould for the papier mâché. Examination of Addendum using an endoscope inserted into the hemisphere cavity from the reverse of the sculpture revealed a solid, smooth, shiny surface inside each hemisphere (fig.10); this could be a commercially sourced ball, or perhaps one that Hesse cast herself.32 The endoscope investigation also revealed that some papier mâché had transferred through the hole through which the rope feeds and spilled into the cavity. Once the papier mâché had been completed, the grey acrylic emulsion paint was then applied, which also appears to have flowed into the internal void.

Fig.11

Eva Hesse

Study for Schema/Sequel 1967

Ink on tracing paper

229 x 305 mm

Private collection

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Fig.12

Eva Hesse

Moulds for the latex hemispheres in Schema/Sequel 1967, consisting of halved rubber balls with a silicone seal on their exterior

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

In her annotated drawing for Schema 1967 (fig.11), a work made soon after Addendum and one of her first to be created using latex, Hesse discusses her use of this same hemispherical shape (or ‘semi-sphere’). Here she used standard Spalding tennis balls cut in half and with a silicone seal on their exterior from which to cast these latex hemispheres (fig.12). In this case Hesse is directly applying the techniques utilised in the fabrication of hemispheres for Addendum, but varying the materials used.

Fig.13

Eva Hesse

Detail of the interior of Addendum showing a knot holding one of the ropes in place

Photo © Tate

Fig.14

Eva Hesse

Study for Sculpture 1967

Varnish, Liquitex, Sculp-metal, cord, masonite

254 x 254 x 25.4 mm

National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Hesse carefully tied the ropes off inside Addendum’s box structure (fig.13) with a knot that she subsequently used as the main formal element in other works, such as Study for Sculpture 1967 (fig.14), No Title 1967 (Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven), Iterate 1967 (private collection) and Constant 1967 (Glenstone, Potomac). It is also interesting to note that Addendum’s ropes were painted after assembly, as suggested by fig.10, where the paint can be seen coming through the hole, confirming that she assembled the work as a whole before painting it.

Fig.15

Eva Hesse

Detail of the reverse of the wooden structure of Addendum showing the lighter grey (upper) and darker grey (lower) paint layers

Photo © Tate

The entire structure of Addendum appears to have been painted in one uniform shade of light grey acrylic emulsion paint of the poly ethyl acrylate/methyl methacrylate (pEA/MMA) copolymer type, containing titanium white and Mars black pigments.33 On closer examination, an additional underlying application of darker grey paint of a similar composition was discovered on the wooden section (fig.15).34

The reasons behind Hesse’s use of the darker grey tone underlayer are unclear. However, Hesse was exploring grey paint during this period, and in several of her sculptures she created a gradual tonal change within the same work. Both Ennead 1966 (Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston) and Untitled (Bochner Compart) 1966 (private collection) feature a darker grey paint at the top that transitions to a lighter grey towards the lower areas. It may be that Hesse was aiming for a similar colour transition in Addendum but changed her mind, or she may have started painting with the darker grey and reassessed the tone before she painted the ropes. Alternatively, she may have used a darker underlying layer to provide depth to the lighter paint on top, a technique that is commonly employed in easel paintings. What is important to note for Addendum is the uniformity of the paint and tone across the work, which critically binds what are two very different materials and textures – papier mâché and rope – into one impactful work.

The coating on the ropes: Could it be artist-applied?

In addition to the paint layers on Addendum, there are two different unpigmented coating layers on the sculpture.35 There is a polyvinyl acetate (PVAc) coating over the entire sculpture, having been applied both on the papier mâché section and the ropes. On the ropes only, there is an additional clear coating on top of the PVAc, identified as an acrylic copolymer emulsion of the poly nbutyl methacrylate/methyl methacrylate (pnBA/MMA) type. This coating has slightly yellowed over time and accumulated a significant amount of soiling. It is unclear whether Hesse applied these coatings herself, or whether they were subsequently applied by conservators in an attempt to protect the sculpture while it is on display. One commercially available pnBA/MMA emulsion is Rohm and Haas’s acrylic latex Rhoplex AC-35, which was introduced in the US in 1967,36 the year Hesse made this sculpture. However, this emulsion was also used extensively as a consolidant – a material applied by conservators to impart solidity and strength – during the 1970s and 1980s in the US and the UK (where it was marketed as Primal AC-35); hence it is also possible that this upper layer was applied by a conservator, although no record of any treatment has thus far been located.

It was critical to the process of treating Addendum to gain more information on the context of the uppermost acrylic coating, and in particular to explore whether Hesse may have applied it herself. If it became clear that Hesse did not apply the uppermost coating, the conservation treatment may also include its removal. However, if the investigations proved inconclusive, the coating would need to be conserved and the risks of swelling and disturbing the coating during cleaning treatment would need to be minimised.

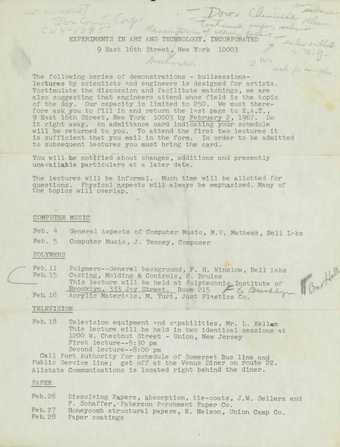

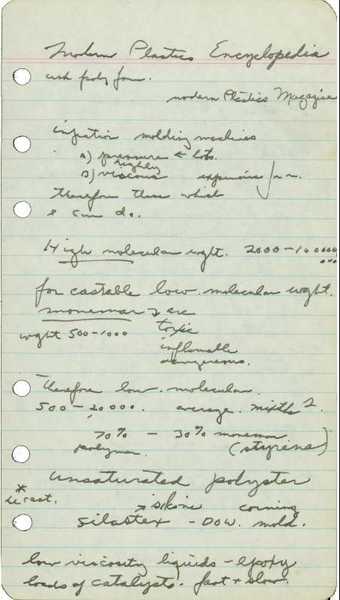

After Addendum: Experiments in Art and Technology

Fig.16

Programme for the Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) lecture series, February 1968, with annotations by Eva Hesse

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

In February 1968, not long after the completion of Addendum, Hesse attended a lecture series in New York entitled Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), which focused on new materials that were being developed by scientists across the US (fig.16).37 This was a collaboration involving scientists and engineers from Bell Telephone Laboratories as well as many artists, most prominently Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman. This partnership is well documented,38 and the performance pieces resulting from it are considered to be critical in the evolution of time-based media art. However, less well understood are the E.A.T. lectures and the influential role they played in Hesse’s subsequent practice.

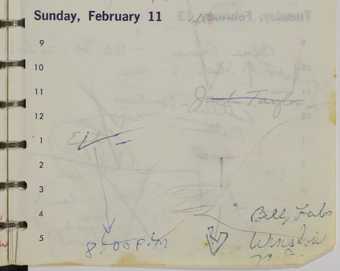

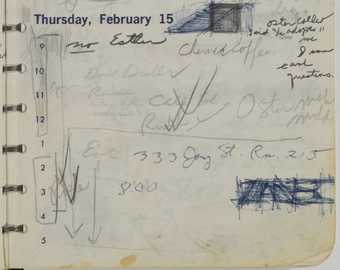

Fig.17a

Page and written entries for 11 February 1968 from Eva Hesse’s appointments diary

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

Fig.17b

Page and written entries for 15 February 1968 from Eva Hesse’s appointments diary

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

Hesse’s diaries show that she attended two lectures in the E.A.T. series on the subject of ‘Polymers’. On the page of her diary for 11 February 1968 are written the words ‘Bell Labs’ and ‘Winslow’, which relate to the first polymers lecture, delivered by F.H. Winslow from Bell Labs (fig.17a). According to the programme outline, this lecture would have given attendees a background on the science of polymers from one of the leading experts in the field. A video of Winslow recorded in 1962 by Bell Labs provides an important insight into the topics these lectures might have covered.39 Hesse’s diary for 15 February includes the notes ‘333 Jay Street, Room 215’ (fig.17b), the location of the second polymers lecture, ‘Casting, Molding & Controls, by P. Bruins’, which was given at the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn. The copy of the E.A.T. programme outline held in Hesse’s archive features her handwritten instructions on how to take the subway to attend this event, and at the top of the page there are notes relating to Dow Chemical, reminding her to ‘ask for samples’ and ‘technical info’ (see fig.16).

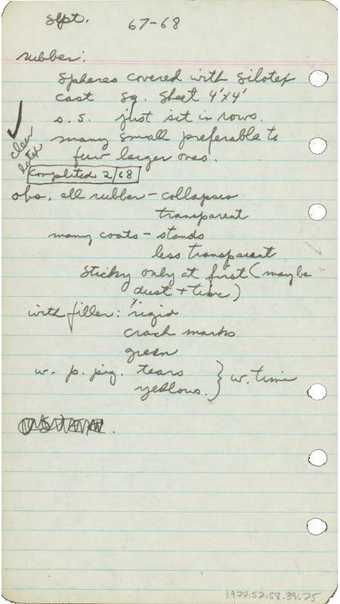

Fig.18a

Page from Eva Hesse’s notebook, 1967–8, showing her notes on the E.A.T. lectures

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

Fig.18b

Page from Eva Hesse’s notebook, 1967–8, showing her notes on the E.A.T. lectures

Eva Hesse Archives, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, Oberlin

© The Estate of Eva Hesse

It is clear that Hesse keenly absorbed the information provided in these lectures, as her notes on them are extensive and detailed. They show her delving into the chemistry of how these polymers are made and how they function, along with extensive detail on casting and moulding techniques (fig.18a). Her thought processes on the manufacture of her work demonstrate a clear understanding of the lecture material and a direct engagement with the information learned (fig.18b). Her notes demonstrate that she worked through the idea of creating spheres covered with a substance called Silotex, also highlighting the pros and cons of the various ways of making them and the resulting aesthetics.40 In fig.18a there is a tick next to ‘clear latex’, and on this curator Elisabeth Sussman writes that ‘The flow, and the flexibility, that she found in Addendum’s cords were qualities that drew [Hesse] to latex.’41

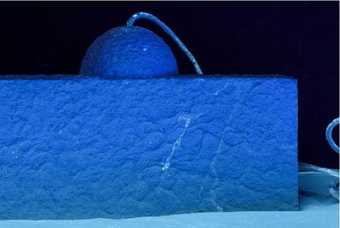

Fig.19a

Eva Hesse

Detail of one of the hemispheres and ropes in Addendum, photographed in ultraviolet light, with the lighter areas representing the acrylic emulsion latex that was brushed unevenly onto the ropes and splattered onto the upper wooden section of the sculpture in the process

Photo © Tate

Fig.19b

Eva Hesse

Detail of one of the hemispheres and ropes in Addendum, photographed in ultraviolet light, with the lighter areas representing the acrylic emulsion latex that was brushed unevenly onto the ropes and splattered onto the upper wooden section of the sculpture in the process

Photo © Tate

Hesse first discovered rubber latex in the autumn of 1967,42 and in an interview with art historian Cindy Nemser in January 1970 she stated, ‘I don’t want to use them [latex and fibreglass] as casting materials. I want to use them directly, eliminating making molds.’43 Hesse was clearly interested in new materials and techniques at the time she was making Addendum, and it is possible that she experimented with the new acrylic-based ‘clear latex’ on the ropes in Addendum with the intention of creating a visual effect, such as enhanced gloss. This coating slightly fluoresces under ultraviolet light, and can be seen spattered and dripped along the side of the wooden section of the sculpture (figs.19a and 19b). This uneven brush application is suggestive of an artist’s hand, rather than the even, careful application typical of a conservator. The coating is also relatively unevenly applied on the ropes, with some areas applied thickly, and other areas with no coating at all. From the likely use of an acrylic emulsion latex on Addendum, Hesse went on to explore the application of rubber latex using a variety of techniques, including brush-applying it as layers over a variety of substrates, including rope, cheesecloth and canvas, or as underlying layers.44

Fig.20

Eva Hesse

No Title 1969–70

Latex, rope, string and wire

Dimensions variable

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

© The Estate of Eva Hesse, courtesy Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Sheldan C. Collins

Hesse applied rubber latex on rope to an extreme degree in No Title 1969–70 (fig.20), where she dipped separate pieces of rope into liquid rubber latex to create one of her last sculptures before her death.45 Interestingly, the ropes in No Title, although unpainted, have been observed as suffering similar types of deterioration to Addendum, such as the ropes sticking to one another and the latex hardening, embrittling and becoming delicate to the touch.46

From these investigations, the possibility that Hesse applied the acrylic latex coating to the ropes in Addendum cannot be ruled out. It is unclear where the artwork was located directly after being displayed in the Art in Series exhibition in 1967, so it is possible that she may have applied the coating sometime before or after the exhibition, if not during the sculpture’s making.

Conservation: A knowledge-producing practice

The extensive investigations into the making of and materials used in Addendum facilitated highly informed decisions around the conservation treatment of this important sculpture. The coating on the ropes, which appears significant in the progression of Hesse’s practice, was painstakingly preserved for the first time through the use of gels created via nanotechnology that allowed the soiling to be gently removed while leaving the sensitive materials underneath undisturbed.47 Hesse’s preparation for this work, including her full-scale drawing, the use of internal supporting balls for the hemispheres, and her layering of paint represent new insights into her working practice. Information gained from exploring her attendance at the E.A.T. lectures also revealed her dedication to the exploration of new materials, forming the basis for much of the experimentation that followed, which potentially incorporated the (at that time) novel acrylic-based ‘latex’ coating. This knowledge-producing practice has contributed to our understanding of the fabrication of Addendum and how this work represents an important, pivotal moment for Hesse, which, when expressed at the material level, arguably marks the overlap between her use of papier mâché and her use of the wider group of materials known as ‘latex’.