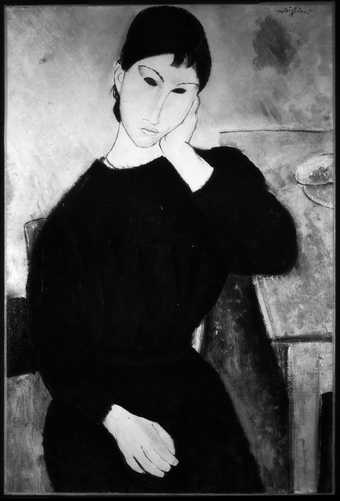

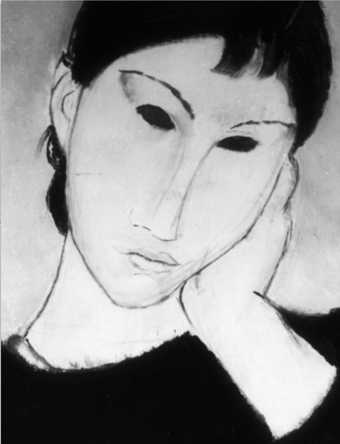

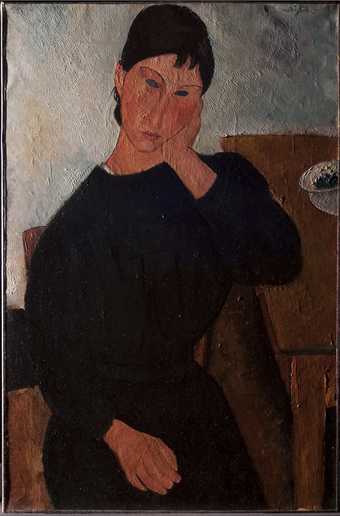

Fig.1

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table 1918–19

Oil on canvas

927 x 605 mm

Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis

C270

Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

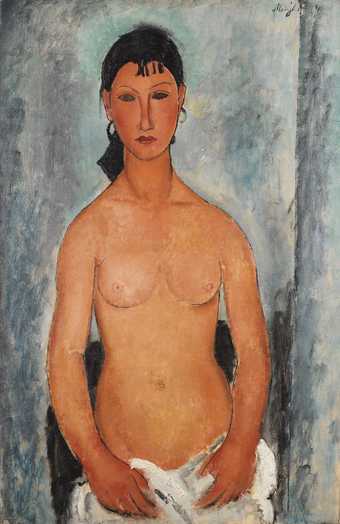

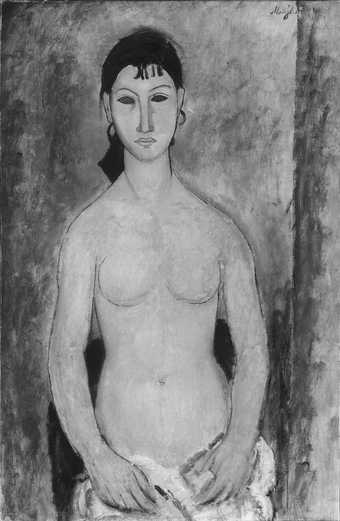

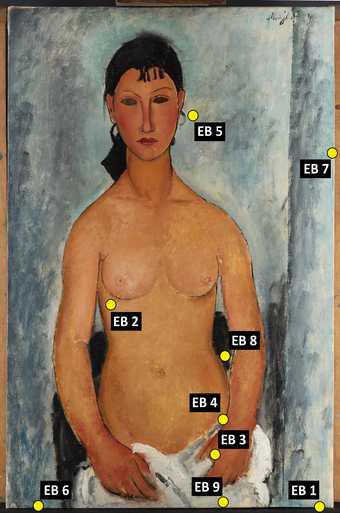

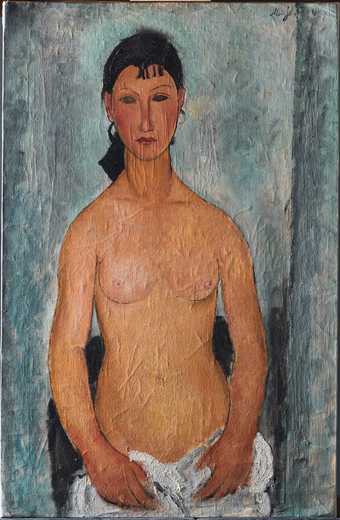

Fig.2

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira) 1918

Oil on canvas

920 x 600 mm

Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern

C272

Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

The model colloquially known as ‘Elvira’ has appeared in as many as four paintings by Amedeo Modigliani, all likely painted between 1918 and 1919.1 Described variously as a ‘child of the people’, a ‘living doll’ and a ‘beautiful model, who, moreover, had warm Italian blood in her veins’, we know little about the life of the woman depicted or about her relationship with the artist.2 Two of these ‘Elvira’ paintings, Elvira Resting at a Table from the Saint Louis Art Museum (C270; fig.1) and Standing Nude (Elvira) from Kunstmuseum Bern (C272; fig.2), were exhibited together in Brussels and Basel in 1933–4, and in Paris in 1981.3 The pictures were reunited at Tate Modern in London in 2017.4 The opportunity to see the portraits side-by-side has provoked renewed interest in the model’s identification, as they clearly feature the same woman.

Uncertainty about the model’s identity has produced conflicting dates for Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira). Several women named or described as ‘Elvira’ had relationships with the artist at different periods, giving rise to a persistent conflation between multiple Elviras who may have served as models.5 Although the two paintings are very different in style and technique from Modigliani’s Parisian portraits and nudes of c.1915–17, they have often been associated with a boisterous entertainer named Elvira, known as ‘la Quique’, with whom the artist had a relationship in Paris from around 1912 to 1914.6 The artist’s daughter, Jeanne Modigliani, argued in her 1958 memoir that the popular association of the Elvira series with the entertainer was likely false, citing the temporal discrepancy between the dates of her father’s relationship with this Elvira and the purported 1918 to 1919 dates of the paintings.7 The memoirs of another member of the artist’s inner circle, Anna Zborowska, puts forward another possible Elvira: an Italian youth who may have modelled for Modigliani in the South of France in 1918–19.8

The technical study of the materials and methods of these two portraits was designed to ascertain if they were executed in close succession.9 The analytical results were then compared with studies of paintings from the different working periods of Modigliani’s practice in order to situate them chronologically within the artist’s oeuvre. The materials and working methods applied to Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) align most closely with those found in Modigliani’s South of France period of 1918–19. Furthermore, taken alongside Anna Zborowska’s account of Modigliani’s time in the South of France, the technical study has narrowed the dating of Standing Nude (Elvira) to 1918. In both pictures, Modigliani portrays the model Elvira with an individuality that is more sensitively developed than the earlier nudes he painted in Paris in 1916–17. However, while the Saint Louis portrait (Elvira Resting at a Table) was drawn and painted quickly, Modigliani’s execution of the Bern nude (Standing Nude (Elvira)) was more extended and exhibits explorations in paint handling that differ from paintings he made before and after. This research enhances an understanding of the artist’s materials and methods and emphasises the challenges of dating Modigliani’s works and identifying his models.

Elvira Resting at a Table: Provenance and reception

When Joseph Pulitzer Jr purchased Elvira Resting at a Table in 1936, he described the painting as synergistic, comprising ‘several threads woven together in a way to engage a young person who had been studying the entire span of art history’.10 Pulitzer’s son cast the picture in a more relatable light, referring to the sitter as ‘The Little Girl Who Wouldn’t Eat Her Spinach’.11 The composition captures a conservatively dressed young woman sitting beside a table. Her body language, perhaps even more than her expression, suggests listlessness, resignation or a moment of idleness. Devoting almost equal attention to face, dress and table, Modigliani resolved the background in his typical sketchy manner to focus attention on the sitter’s solid-blocked eyes and elongated posture.

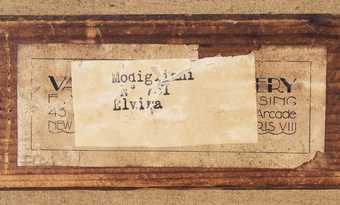

Fig.3

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, collection label from Valentine Gallery, New York on the central crossbar of the stretcher in printed ink and superimposed by an exhibition label

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Elvira Resting at a Table was first illustrated in Pfannstiel’s 1929 catalogue raisonné as ‘Elvira accoudé à une table’, where it was listed as being in the collection of Modigliani’s patron Léopold Zborowski.12 It was later associated with the Galerie Simon, Paris, and was in the collection of the dealer Paul Guillaume by 1929. Pfannstiel’s catalogue raisonné of 1956 provides an alternate title of ‘Elvire, enfant du peuple’,13 which also appears on a label from the Guillaume collection on the back of the stretcher.14 The painting appeared under this name when it was exhibited in Brussels and Basel in 1933–4.15 Pulitzer purchased the painting in New York in 1936 from the Valentine Gallery, with which Guillaume had a reciprocal business relationship (fig.3). In 1968 Pulitzer gifted the portrait to the City Art Museum of Saint Louis (now Saint Louis Art Museum).

In her review of the 1931 exhibition Since Cézanne at the Valentine Gallery, Rose Mary Fisk described Elvira Resting at a Table as encapsulating Modigliani’s modern, distinctive style, marking him as an outsider in the group show: ‘Modigliani’s portrait of “Elvira” does not seem quite at home here. This is an artist too individual and too highly personal to be sociable.’16 Another review mentioned the sitter’s emotive posture, describing it as ‘haunting in its melancholy of pose and expression’.17 Pfannstiel similarly described the work as ‘mélancholique’ in his 1929 catalogue, where he goes on to highlight the sitter’s ‘doll-like simplicity’.18 Such readings presage later criticisms that the sitter known as Elvira appeared ‘innocent and pathetic’, and ‘openly rustic and illiterate … without thoughts’.19

Standing Nude (Elvira): Provenance and reception

The young woman of Standing Nude (Elvira) stands frontally, holding a white cloth to preserve her modesty. Her expression is reserved, perhaps slightly dismissive. Her refined facial features contrast with her more roughly painted body and strong arms. The rapidly sketched background – from the light blue ‘aureole’, or halo, around the face, to the darker blue and black vertical sections on either side of the figure – allows the outline of the figure to stand out clearly.

Standing Nude (Elvira) received early international attention. The first documented illustration of the painting appeared in 1921 as a black and white image in a review of a Geneva exhibition published in the periodical L’Amour de l’art.20 It then appeared in the Czech art magazine Volné směry: měsíčník umělecký in 1923 and in the German art and decoration magazine Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration in 1925.21

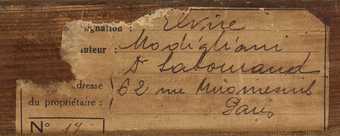

Fig.4

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), collection label from ‘Dr Sabouraud’ on the reverse of the frame, central crossbar

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

Armand Parent is the assumed first owner of the painting, based on the memories of his daughter Denise Parent.22 In 1926 André Salmon published a black and white photograph of Standing Nude (Elvira) in his biography of the artist,23 in which he listed the dermatologist Raymond Jacques Sabouraud as owner of the painting, corresponding to an exhibition label on the reverse of the strainer listing the title simply as ‘Elvire’ (fig.4).24 The 1933 and 1934 exhibition catalogues from Basel and Brussels also identify Sabouraud as the owner. The work certainly belonged to Sabouraud until 1937.25 The writer Charles Douglas records that postcard reproductions of Standing Nude (Elvira) were in circulation by 1941 and that the picture was by then publicly known.26 Raffaello Franchi names the ‘coll. dott. Sabouraud’ in the provenance in 1944, six years after Sabouraud’s death.27 Collectors Walter and Gertrud Hadorn from Bern acquired the painting by 1956 and presented it to Kunstmuseum Bern in 1977.28

The literature on Standing Nude (Elvira) has focused on identifying the model and dating the painting.29 Recent scholarship demonstrates an increasing interest in the question of the young woman’s identity, specifically in the context of rapidly changing depictions of women and modernity in France.30

Challenges in dating

The challenges in dating Modigliani’s paintings, despite his short career, are well documented. They originate from the absence of artist’s dates and incongruities among catalogues raisonnés and illustrations.31 Establishing a precise date for Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) is no exception; this is clearly demonstrated by the revolving range of dates given to the painting, spanning a period from 1916 to 1919.

The chronology of the two paintings is further complicated by the appearance of the same model ‘Elvire’ or ‘Elvira’ in at least four paintings by Modigliani. Three of these paintings are of similar size and early references to them are rarely illustrated. Additionally, the works have often been associated with similar naming conventions – with such titles, for example, as simply ‘Elvira’ and ‘Child of the People’. Therefore, the paintings are plausibly interchangeable when presented solely via textual evidence, without an accompanying image. Translations and generic descriptions have also complicated identifying and dating each painting.

The first date assigned to both Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) was 1919.32 The catalogues of the exhibitions in Brussels in 1933 and Basel in 1934, however, dated the Bern painting to 1917 and the Saint Louis painting to 1918.33 Christian Parisot’s catalogue raisonné of 1990 also dates the Saint Louis painting as 1918, while an earlier source by Adolphe Basler published in 1931 dates it to 1916–17, although this is an outlier.34 Elvira Resting at a Table was dated to 1919 by Gotthard Jedlicka in 1958 and by Corrado Pavolini in 1966.35 Ambrogio Ceroni’s catalogue raisonné of 1965 dates both paintings to 1919, but his later catalogue raisonné of 1970 dates both paintings to 1918.36

Despite the shifting dates, a reasonable consensus may be derived from the dates given closest to the artist’s lifetime and in Ceroni’s catalogues raisonnés. These, combined with the results of the technical analysis and freshly considered contextual evidence, strongly corroborate the dating of the paintings with Modigliani’s time in the South of France between 1918 and 1919.

The sitter: Anecdotes

Modigliani perpetuated the mystery of Elvira’s identity by omitting any surname. The strong sense of individuality captured in Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) warrants an examination of the Elviras known to have crossed the artist’s path. The sitter was described by Jeanne Modigliani as a ‘woman with an oval face, black hair tied up in a bow, and a young but monumental body; the catalogues call her Elvira’.37

Anna Zborowska’s reminiscence, published posthumously in 2015, helps identify Modigliani’s sitter. She describes Elvira as a teenager who lived nearby Cagnes-sur-Mer, where Modigliani was staying between 1918 and 1919, accompanied by his partner Jeanne Hébuterne:

Elvire, a very young teenage girl, posed for [Modigliani] for a nude, which bears her name and is one of the most beautiful. Among the deep blue, the amber body stands out, upright, black eyes looking far off. With both hands, in a very simple pose, she holds a white sheet. Gossips whispered that Jeanne was madly jealous of the beautiful model, who, moreover, had warm Italian blood in her veins.38

Until Zborowska’s memoir, which so faithfully describes Standing Nude (Elvira), came to light, scholarship has presupposed the sitter to be another Elvira, the woman known as ‘la Quique’ who had a tumultuous romantic relationship with Modigliani in Paris around 1912–14. In his book on the Parisian districts of Montmartre and Montparnasse, Charles Douglas dedicates a chapter to this Elvira, whom he describes as an extroverted and temperamental entertainer from Marseille.39 Douglas refers to a Madame Gabrielle, who is said to have known her: ‘It must have been 1906 when I met her touring. She said she was twenty-four but she looked, and I say it, not more than twenty. Everybody loved her, she was really beautiful and so funny. She used to keep the crowds in fits of laughter.’40 There is consensus among scholars that Modigliani’s relationship with ‘la Quique’ took place before the First World War of 1914–18, at which time Elvira would have been between twenty-seven and thirty years old.41 As the paintings likely date to 1918–19, this would place ‘la Quique’ at thirty-three to thirty-five years old and unlikely to be described as ‘teenage’.

In 1958 Jeanne Modigliani outlined the temporal inconsistencies inherent in attempts to connect ‘la Quique’ with the Elvira portraits.42 If the paintings date to Modigliani’s period in Cagnes-sur-Mer, around 1918 to 1919, this would imply that Modigliani painted Elvira ‘la Quique’ from memory – an assumption that would challenge the painter Léopold Survage’s widely accepted statement that Modigliani always painted directly from the model.43 Nevertheless, the attribution of ‘la Quique’ as the model for the Elvira portraits has persisted. The catalogue for an exhibition held in Martigny in 2013, for example, illustrates both Standing Nude (Elvira) and Elvira Resting at a Table, alongside a description of the sitter: ‘The daughter of a prostitute and an unknown father, Elvira, called “la Quique”, left Marseille when she was fifteen for Paris … Elvira would become the muse, model and lover of Modigliani, with whom she shared the same free and bohemian spirit.’44 Albeit young and beautiful, this coquettish entertainer does not readily match the reserved model portrayed in Standing Nude (Elvira) and Elvira Resting at a Table, nor the very young teenager described by Zborowska.

Zborowska’s memoir introduced a youthful Italian who sat for Modigliani in the South of France as a new alternative to ‘la Quique’ for Elvira’s identity. The alignment of this Elvira with Modigliani’s period in Cagnes-sur-Mer resolves the disparities that result from the attempt to date the portraits to Modigliani’s earlier period in Paris, instead supporting their likely execution in 1918–19. It must be noted that Zborowska’s description was shared retrospectively. Her precise description of the painting, however, provides a convincing match with Standing Nude (Elvira).

The young Elvira described in Zborowska’s recollections is in strong accordance with the same model captured in Elvira Resting at a Table and Elvira with a White Collar 1918 (private collection; C269). Unlike many of Modigliani’s figures, Elvira Resting at a Table portrays the sitter dressed in clothing that is not particularly fashionable, but conservative and practical. Elvira with a White Collar captures the sitter in a similarly modest and utilitarian dark dress, which Jeanne Modigliani likens to the dress of a schoolgirl.45 Zborowska’s description of Elvira fits convincingly with these portraits, which convey a rather reserved but strong, youthful personality.

A similar characterisation can be observed in Standing Nude (Elvira). A sense of disquiet sets the painting apart from Modigliani’s cycle of more sultry, provocative nudes made only a year or so earlier, such as those of 1917 in the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (C186 and C199).46 The sitter’s firm and steady posture and her ruddy complexion, described by one critic as ‘a bit too florid in the face’, speak more to a transitional state, caught perhaps while disrobing, washing or dressing.47 Perhaps this undressed Elvira, a strong adolescent female, would be portrayed by Modigliani as a portrait rather than as a provocative or even atelier-style nude.

The strong sense of individuality conveyed by these pictures is an important consideration in understanding the identity of the sitter. As one critic recalled of Elvira Resting at a Table in 1929, Modigliani’s ‘untrammelled sense of characterization was responsible for some of the most pertinent and lasting portrait impressions that I know’.48 Curator Nancy Ireson writes of both portraits:

Her nonchalance, not her dress with a rounded collar, is her true uniform. Given his careful rendition of fashions and flesh alike – which capture clothing and body confidence he would not have encountered in provincial Italy – it seems reasonable to assume that Modigliani was interested in the ways in which women chose to present themselves.49

Format and supports

There are striking similarities in the format, dimensions and stretching of the canvas supports of the two Elvira paintings. Both are on standard-sized marine 30 canvases, a format traditionally used horizontally for seascapes, but which Modigliani turned 90 degrees to create an elongated portrait support. Marine formats appear in his work from 1908 onwards but are predominantly documented during the period he spent in the South of France between 1918 and 1919, when the financial support of Zborowski likely enabled him to acquire his preferred materials and supports.50

Fig.5

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), reverse

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

Fig.6

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), lower crossbar with the standard format stamp ‘30 M’ (right) and the lower left corner joint

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

Fig.7

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), detail of lower tacking edge. The rounded brushstroke illustrates that the brush was pulled slightly over the edge. Visible nail holes all match the perforation in the wood (the staples were added later); the orientation mark for tacking is visible in the centre

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

Standing Nude (Elvira) is unlined and stretched on a 920 by 600 millimetre chassis ordinaire (fig.5), a five-member strainer with a horizontal crossbar and half-lap joints, fixed with four nails in each corner; the format stamp ‘30 M[arine]’ is applied to the lower crossbar (fig.6).51 This tensioning system was common in France at the time and identical or similar strainers appear in works Modigliani made both before and during his time in the South of France.52 Brushstrokes overlapping the lower tacking edge (fig.7) indicate that when Modigliani painted the Bern Elvira it was stretched to this format and likely on this strainer.

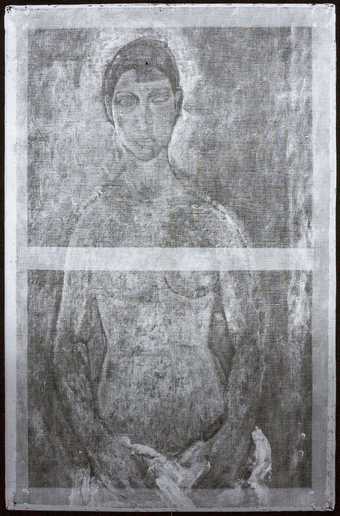

Fig.8

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, reverse in incandescent light

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Fig.9

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, X-radiograph with the contrast digitally enhanced, captured at 35 kV

Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

The Saint Louis Elvira is unlined and stretched over a wooden slot mortise-and-tenon joint stretcher with one horizontal crossbar and ten keys (fig.8). Although the stretcher is sized according to a standard 30 marine format, it is keyed out to 927 by 605 mm. Tape extending from the painted surface to the wooden stretcher verso currently prevents adequate inspection of the tacking edges. The verso of the stretcher retains a partially visible label from the Valentine Gallery, where the picture was shown in 1931 and 1936, and another referencing Paul Guillaume’s collection, which suggests that if the canvas was restretched, this occurred before 1936.53 While stretchers – as distinct from strainers – appear to be rare in Modigliani’s oeuvre, other examples, such as Jeanne Hébuterne 1919 (C326) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, may represent the use of original stretchers.54 An X-radiograph of Elvira Resting at a Table (fig.9) indicates the possibility of alternate tacking sites in the tacking margins, but these are few in number and do not provide definitive evidence that the painting was restretched.

Underdrawings: Depicting anatomy

Fig.10

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, infrared reflectograph, 900–1700 nm transmission

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Fig.11

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), infrared reflectograph, 1035–2000 nm transmission, showing the contours outlined in a smooth and continuous line in graphite pencil, focusing on the figure’s features, the muscular map and the vertical axis of the figure

Photo © Markus Küffner, Bern University of the Arts

Fig.12

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, detail from the infrared reflectograph showing contour editing of the face, neck and ears

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Fig.13

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, detail from the infrared reflectograph showing placement editing of the lower hand

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Infrared reflectography (IRR) reveals that Modigliani used a carbon-based medium for the underdrawings of both paintings (figs.10 and 11).55 While some underdrawing is visible to the naked eye in Elvira Resting at a Table – in the contouring of the figure’s lower cheek, for example – it is clearer in IRR images (figs.12 and 13). Modigliani made small adjustments to these contours during painting, and yet his long, often uninterrupted lines signal his confidence in the composition. Furthermore, the underdrawing’s concentration on the face, hands, and figure’s posture indicate that these areas were his focus. The bowl of greens exhibits concrete outlining, but the remaining elements – table, chair, dress and background details – were delineated purely with paint.

Fig.14

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), transmitted infrared reflectography, detail showing adjustments at the neck and shoulder, and irregularities in paint thickness

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

The IRR of Standing Nude (Elvira) shows long fine lines, presumably drawn with carbon-based media, that deviate slightly from the visible outlines in paint. Like the Saint Louis Elvira, the artist used drawing to map out the figure’s features, such as the lips, breasts and hands. The lines appear to sketch inward towards joints, designating musculature for the forearms and marking the central axis of the figure. A few minor adjustments of this design layer are also visible in the lines of the shoulders, neck, lips and breasts (figs.11 and 14).

Brushstrokes, blocked-in shapes and contouring lines

Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) share several painting techniques in common, including stabbing brushstrokes made with large round brushes, overlapping brushstrokes made with square-tipped stiff brushes, textured backgrounds, and paint applied in distinctive zig-zag patterns. These techniques are characteristic of Modigliani’s practice during his South of France and later Paris years.56

Fig.15

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), X-radiograph captured at 28 KV

Photo © Thomas Becker, Bern University of the Arts

Modigliani adjusted compositional forms as he painted, as shown in the multiple layers of brushstrokes, blocked-in shapes and contour lines visible in X-radiographs (figs.9 and 15). The contours appear as dark lines surrounded by white areas, indicating thickly applied paint containing lead white. This feature is particularly evident in the faces, eyes and the edges of the figures’ bodies. The outlines of the shapes are reinforced with high impasto, which enhances the contrast of the darker contour lines in the X-radiograph. In Standing Nude (Elvira), outlines were intensified with dabbed brush application, as in the shoulders and hair. The background of Elvira Resting at a Table is dominated by diagonally applied and contrasting brushstrokes. Modigliani first delineated the outlines of the forms with the contours left in reserve before articulating them with fluid black paint.

Fig.16

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, detail showing the techniques of outlining contours (visible white ground layer) and paint scraped to create hair texture

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Fig.17

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), detail showing the negative outlining technique and the skin tone layer built around the fringe, contour lines that are traced several times and accentuated (for instance, the yellow line for the chin), and paint that has been scraped to create hair texture

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

Modigliani created texture by using a blunt-tipped object, likely the end of a paintbrush, to scrape away wet paint, leaving the ground layer visible through thin, translucent layers of remaining paint. This technique is used in both paintings for the sitter’s hair in the later phases of painting (figs.16 and 17) and is one of the key identifiers of this model. In the nude portrait, the X-radiograph shows that Modigliani first applied a thick preliminary layer of white underpaint to the figure, the face and the halo around the face, avoiding the hair (fig.15). The hair along the neckline was added later, however, as the background was painted and over the white underlayer.

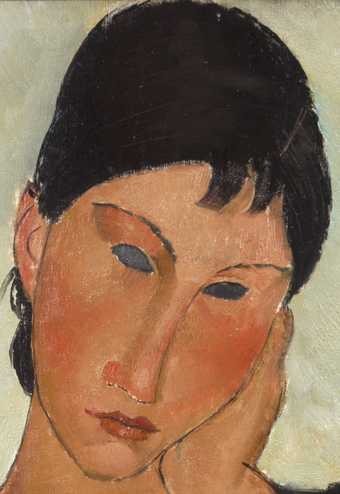

Fig.18

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), detail showing the left eye with negative outlining technique (eye contours, brow) and layering technique

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

The face of Standing Nude (Elvira) was first built with a base layer of pink, dappled brushstrokes, leaving the eyes, eyebrows and lips in reserve (fig.18). The artist then painted the hair and fringe at the top of her head. A white modelling layer was placed on top of the pink base layer, avoiding the fringe and the right side of the chin. This modelling layer was followed by a more liquid, binder-rich yellow layer. In Elvira Resting at a Table, the hair at the nape of the sitter’s neck was added after the artist applied the skin tones of the figure’s face and the base colour of the hair. He returned at a later date with another layer of skin-tone paint and reinforced Elvira’s signature clusters of fringe with two brushstrokes. A few topical strokes of fringe-defining black paint on the forehead of Standing Nude (Elvira) show that Modigliani also returned to the picture, seemingly determined to provide his sitter with this identifying feature.

Fig.19

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table photographed in raking light from the left

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Both Elvira paintings share a layering structure based on local underpainting. The backgrounds, with similar palettes of pale blues, blue-greens, greys and purples are painted with gestural brushstrokes that lead the viewer’s eye towards Elvira’s steady gaze. In the Saint Louis painting, the artist used a wide, round-bristled brush to block in the warm brown and black tones of the lower background and the light grey, green and blue tones of the upper background with binder-rich, thinly applied paint. Using a wider, rounded brush, the artist then applied hues of light blue, yellow, greyish blues and purple with thicker binder-rich paint to the upper background. He swept the brush diagonally down and towards the right before lifting it abruptly upwards, perpendicular to the picture plane, to leave wet, swiftly daubed patterns of medium impasto. Raking light photography highlights the liquid nature of the paint, the height of the impasto and the decisive directional brushwork (fig.19).

Fig.20

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, detail showing the left eye with negative outlining technique (eye contours, brows) and the broken eyebrow line

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Fig.21

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), detail showing the lower left corner with rapidly drawn zig-zag brushstrokes. Cobalt blue was identified in the saturated dark blue paint located at the lower border edge (centre of the image) (see Table 1)

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

The wet-in-wet technique is the dominant technique applied to the Saint Louis Elvira, evincing that the artist worked quickly over layers of thinly applied underpaint with more binder-rich, medium-to-high impasto paint. He used this technique especially for light hues and facial features, and to reinforce contour lines (fig.20). The background of the Bern Elvira is less elaborate and was painted more quickly, but it also shows the characteristic interplay of dabbed and rapidly drawn zig-zag brushstrokes (fig.21). The dappled texture and thinness of the background – even more pronounced than that of the Saint Louis painting – resembles the luminous, fluid painterly style Modigliani used in the South of France, with its lean and rapidly applied brushstrokes that allow the light ground to shine through.

Ground and paint layers

X-ray fluorescence analysis (XRF), polarised light microscopy, and scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM-EDX) of paint cross-sections containing ground layers and skin tones provided further information about the layer structure and materials of the two Elvira paintings (figs.22, 23 and 24, and Table 1).57

| Table 1: Analytical results | Elvira Resting at a Table Saint Louis Art Museum C270 |

Standing Nude (Elvira) Kunstmuseum Bern C272 |

| Ground layer pigment | ||

| Methods | LM+SEM-EDX, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR-FPA, XRF | LM+SEM-EDX, FTIR spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR-FPA |

| Result: Ground layer 2 | Sample ESL 2 (ground layer and flesh paint): lead white, minor quartz | Sample EB 2 (ground layer 2 and flesh paint): lead white, minor quartz, minor barium sulphate |

| Sample EB 1 (ground layer 1+2, blue paint layer): lead white; barium sulphate; ochre, iron-oxide yellow, trace of Ti in combination with Fe; one single ultramarine blue particle; minor aluminium silicates; trace of Cu | ||

| Result: Ground layer 1 | Sample EB 1 (ground layer 1+2, blue paint layer): calcium carbonate; minor quartz; only a few lead white particles | |

| Ground layer binding media | ||

| Methods | FTIR spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR-FPA | FTIR spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR-FPA |

| Sample ESL 2 (ground layer and flesh paint): hydrolysed and saponified oil (esters, carboxylates, lead stearates) | Sample EB 2 (ground layer 2 and flesh paint): partially hydrolysed and saponified oil with a high content of lead stearates | |

| Paint layer pigments | ||

| Methods | LM+SEM-EDX, FTIR spectroscopy, XRF | Raman 785nm+LM+SEM-EDX, FTIR spectroscopy |

| Flesh tone paint |

Sample ESL 2 (ground layer and flesh paint): vermilion; iron oxide red; barium sulphate; quartz; aluminium silicates XRF 6 (lip): vermilion, lead white, earth pigment, chrome yellow, barium sulphate |

Sample EB 2 (ground layer 2 and flesh paint): lead white; vermilion; ochre; iron oxide red; gypsum; quartz; aluminium silicates; celestine, phase associated with natural gypsum plumbonacrite; gypsum possible |

|

XRF 4 (right cheek): vermilion; chrome orange possible |

Sample EB 3 (flesh red, left hand, FTIR only): major barium sulphate; lead white, gypsum; vermilion | |

| Sample EB 4 (flesh yellow, hip, FTIR only): lead white; gypsum; chrome yellow | ||

| Yellow | XRF 3 (background yellow), 8 (table): ochres; chrome yellow possible | Sample EB 5 (background yellow, FTIR only): lead white; minor gypsum; chrome yellow; minor vermilion |

| Blue | XRF 7 (background, blues dominant), 9 (left iris of eye): Prussian blue | Sample EB 1: (ground layer 1+2, blue paint layer): cobalt blue PB36 (cobalt-chromite-aluminate); lead white |

| Sample EB 6 (background dark blue, FTIR only): lead white; gypsum; cobalt blue; minor Prussian blue | ||

| Sample EB 7 (background light blue, FTIR only): lead white; minor Prussian blue | ||

| Black | XRF 1 (dress): bone black; iron oxide black possible | Sample EB 8 (black chair, FTIR only): lead white; minor gypsum; minor bone black; carbon black; minor Prussian blue |

| Brown | XRF 2 (chair), 8 (table): ochres, iron oxide possible | |

| Green | XRF 5 (leafy greens): emerald green, viridian possible, chrome-based green possible, copper-based green possible | |

| Paint layer binding media | ||

| Methods | FTIR spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR-FPA | FTIR spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR-FPA |

|

Sample ESL 2 (ground layer and flesh paint): hydrolysed and saponified oil binder (esters, carboxylates) |

Sample EB 2 (ground layer 2 and flesh paint): partially hydrolysed and weakly saponified oil | |

|

|

Sample EB 3 (flesh red, left hand, FTIR only): oil with saturated hydrocarbon, protein | |

| Sample EB 4 (flesh yellow, hip, FTIR only): oil with saturated hydrocarbon, protein | ||

| Yellow background | Sample EB 5 (background yellow, FTIR only): oil with saturated hydrocarbon, major protein | |

| Sample EB 5 (background yellow, ATR-FTIR-FPA): protein on top of the paint layer (coating or possible consolidation residues) | ||

| Blue background | Sample EB 7 (background light blue, FTIR only): oil | |

| Black | Sample EB 8 (black chair, FTIR only): oil | |

| Varnish | ||

| Methods | FTIR spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR-FPA | FTIR spectroscopy, ATR-FTIR-FPA |

| Natural resin | Protein, natural resin | |

| Sample ESL 2 (ground layer and flesh paint): natural resin | Sample EB 9 (FTIR only) confirmed by Sample EB 2 (ground layer 2 and flesh paint): natural resin | |

Table 1

Results of analyses of paint from Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) with LM+SEM-EDX, FTIR, ATR-FTIR-FPA that were carried out by Nadim C. Scherrer and Stefan Zumbühl at the Art Technological Laboratory, Bern University of the Arts. The XRF analysis was carried out by Courtney Books (for technical information, see note 57)

Fig.22

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), sample map indicating the areas that underwent analysis. Sample sizing, as suggested by the yellow dots, has been increased here for clarity of graphic representation, and is not representative of actual measurements

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern / Map courtesy of C. Books

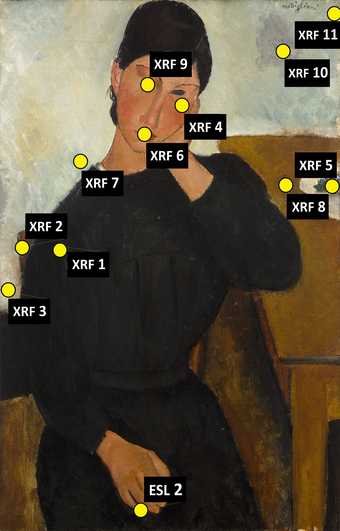

Fig.23

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, sample map indicating the areas that underwent analysis. Sample sizing, as suggested by the yellow dots, has been increased here for clarity of graphic representation, and is not representative of actual measurements

Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum / Map courtesy of C. Books

Fig.24

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira), SEM-EDX, image and spectra for cross-sections from Elvira Resting at a Table (Elv2) and Standing Nude (Elvira) (P13 refers to EB2, Table 1). The different morphology of the lead white particles in the ground layers is clearly visible

Photo and analysis © Nadim C. Scherrer, Art Technological Laboratory, Bern University of the Arts

In both Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira), analysis indicates hydrolysed and partially saponified oil as the main binder component in the ground and paint layers. The binding media analyses show no evidence of water-based medium mixed with an oil medium (i.e. tempera or emulsion paints). The appearance of lean emulsion tempera (casein tempera) analysed in some of Modigliani’s later works of 1918–19 has been linked with the artist’s desire for faster drying properties; during this period he also began to favour thinner paint applications and medium-diluted pigments, attributes found in both Elvira paintings, that similarly rendered faster drying effects.58

In the commercially applied ground layers, lead white was the main white pigment detected, with formations of lead soaps. The morphology of the lead white particles shows clear differences between the ground layer compositions, indicating that a different quality of paint was used in Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira). Samples of skin tones from both paintings include vermilion, iron oxide red and natural red ochre in addition to lead white (fig.24). The paint layers also contain barium sulphate, quartz and aluminium silicates as extenders. The composition of the skin tones suggests the use of a comparable or even identical tube colour in both paintings (see Table 1), including yellow ochre and chrome yellow. Technical investigations show that chrome yellow appears more often in the works Modigliani painted in the South of France versus other periods.59 The green pigments in the Saint Louis painting – the emerald green and viridian or chrome-based green used for the dress and the bowl of leafy greens – are identical to those identified in earlier analyses. Prussian blue appears in both Elviras, which is consistent with previous analyses of other late paintings by Modigliani.60 The cobalt chromite blue identified in the Bern painting is a noteworthy anomaly and is discussed below.

Discrepancies in canvas supports

The canvas supports of both Elvira portraits are unlined and are made from bast fibres but differ in visual and tensile properties. High-resolution X-radiographs of the paintings were examined by the Thread Count Automation Project (TCAP), which uses software to calculate and map canvas weave densities and local thread angle variations.61 Results from the TCAP support that Modigliani used canvases that he garnered from various sources, as is likely in the case of Elvira Resting at a Table, as well as cutting some from the same canvas roll, as is likely in the case of Standing Nude (Elvira).

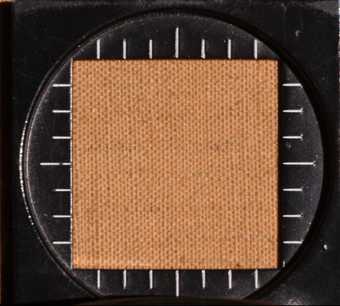

Fig.25

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, detail of the textile support, scale window equal to 2.54 cm

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

Fig.26

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), detail of the textile support with custom stamp and the remains of glued paper

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

The Saint Louis portrait aligns with Modigliani’s preferred canvas weight and is of a dense plain weave, a physical quality associated with enhanced tensile strength and, therefore, often considered of higher quality (figs.8 and 25). The TCAP report indicates an average horizontal thread count of 27.5 (δ 0.8) and vertically of 21.3 (δ 0.8), with visual emphasis along the vertical corrugation of the warp threads. The Bern portrait is painted on a typical plain-weave canvas now darkened to a brownish tone (figs.5 and 26). The vertically running warp threads are thicker than the more densely woven weft threads that run horizontally, resulting in a rougher-woven canvas; no selvedge is present.62 According to the TCAP results, the thread count is 18.9 horizontally (with standard deviation δ 0.2) and 17.4 vertically (δ 0.6).

Fig.27

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira) in raking light from the left showing the vertically pronounced craquelure, influenced by the mechanical properties of the textile support and ground layers

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

Significantly, TCAP results indicate that Standing Nude (Elvira) matches with three other paintings, all dated to 1918–19, that were likely sourced from the same pre-primed canvas roll.63 The textile support of Standing Nude (Elvira) shows particularly strong similarities with roll match mate Madame Zborowska 1918 in the Tate collection.64 The portraits were painted on a similar type of canvas with ground layers that appear to be identical. Both show important thread count deviations in the vertical direction, which also match the vertical thickness irregularities of Standing Nude (Elvira). This is visible by looking closely at the canvas detail (fig.26). The canvases of both Standing Nude (Elvira) and Madame Zborowska may be considered low quality in terms of mechanical properties and durability, as the cracking patterns of the former painting show in raking light (fig.27). These variations in canvas type and quality indicate Modigliani’s choice, possibly driven by economic necessity, to utilise a variety of textile supports.

Contrasting ground layers

Modigliani used a number of different priming systems, including commercially primed canvases and multi-layered coloured grounds.65 Both paintings in this study have very light or white pre-primed grounds, yet they differ significantly in structure and composition. The two-layer ground of Standing Nude (Elvira) is slightly off-white, confirmed by the presence of isolated blue and ochre particles (see Table 1). Visual examination suggests a two-layer preparation that was confirmed by a paint cross-section. The lower ground layer is based on calcium carbonate, with some quartz particles and a few lead white particles. The thicker, upper ground layer consists of mainly lead white, with some large barium sulphate particles, a few particles of aluminium silicate (kaolin), the odd particle of yellow iron oxide and a single particle of blue ultramarine. Madame Zborowska has an identical preparation structure. Therefore, it may be possible that the supports derived from the same production line were associated with the same supplier.66

In contrast, the ground layer of Elvira Resting at a Table is homogenous, consisting mainly of lead white with a little quartz. Different morphology between the lead white particles is also discernible between the two Elvira paintings. The SEM image shows that the particles in the Bern painting are predominantly in the form of large unidirectional platelets. In the Saint Louis painting, priming particles are smaller, less directional and compressed into larger agglomerates (fig.24). The different production processes and the lesser quantity of extenders in the Saint Louis painting suggest that a higher quality paint was used for its priming.67

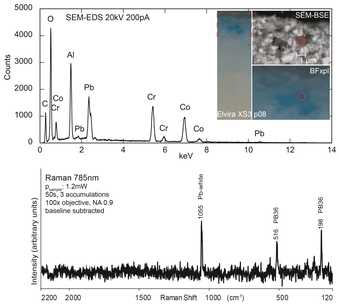

An unusual pigment discovery

Fig.28

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), SEM-EDS (top) and Raman 785 nm (bottom) spectra of a blue particle in the blue paint layer, identifying cobalt-chromite blue-green spinel PB36 surrounded by lead white (BFxpl = bright field with crossed polars)

Photo and analysis © Nadim C. Scherrer, Art Technological Laboratory, Bern University of the Arts

Modigliani’s use of cobalt chromite blue in Standing Nude (Elvira) is of particular note, as the pigment has not been previously identified in his work. FTIR applied to two micro-samples taken from the dark blue background at the lower edge confirmed cobalt components, and SEM-EDX analysis identified distinct blue particles as cobalt-chromite aluminate (PB36) and lead white (fig.28 and Table 1).68 There is no published evidence of the use of cobalt chromite blue in oil paintings prior to this research. In historical sources, the pigment is referred to as ‘blue-green oxide’ and is rarely mentioned in evolutions of cobalt-based pigments.69 The earliest reference dates to 1906, where the production of ‘turquoise green’ is described in the chapter on ‘cobalt green colors’ and associated with painting on porcelain.70 In contemporary pigment production, the pigment is briefly mentioned in manufacturers’ literature and is hardly known in the field of technical art history.71 Analyses by the Doerner Institute in Munich recently verified the use of the cobalt-chromite aluminate pigment in a painting dating from 1911 by Emil Nolde as well as in a Behrendt oil paint sample named ‘blue-green oxide’.72 Although PB36 has not been analytically proven in other paintings by Modigliani to date, there are indications that suggest his additional use of the variant. In the underlying composition of the 1919 Portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne (C327), SEM-EDX analyses conducted at C2RMF of an ‘Aluminate de cobalte et chrome’ were interpreted as cerulean blue.73 Pairing this analysis with Raman spectroscopy may confirm this pigment rather as cobalt chromate blue PB36, as analysed in Standing Nude (Elvira). Beyond new relevancy to technical art history, such pigment analyses carry potential for the dating and attribution of Modigliani's work.74

Variable working process: Figure versus background

Although there are important similarities in the applied tones and brushstrokes of the two Elvira paintings, Modigliani used different techniques to create distinct visual effects. These divergences are discernible in each paint layer applied during the artist’s working process.

Fig.29

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), detail of the navel showing the flattened, smoothed, island-like texture of the underpaint

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

Fig.30

Amedeo Modigliani

Standing Nude (Elvira), detail of the waist showing the 2–3 cm wide vertical spatula mark

Photo courtesy of N. Bäschlin / Photo © Kunstmuseum Bern

To review, Modigliani used a preliminary, lean paint layer to block in the general design for both paintings. However, in Standing Nude (Elvira) a divergent technique appears in the preliminary layer that has not yet been mentioned in relation to Modigliani’s paintings: in the background around the face and the hair, as well as within the face and the torso, a lean white paint is applied viscously with a brush and then smoothed with a spatula or palette knife. The applied morphology of the layer is non-continuous, as the isolated, spotted brushstrokes remain visible after smoothing, to leave a textured topography reminiscent of island formations (fig.29). There are noticeable horizontal and vertical markings, created by smoothing or reducing the layer with a flat tool to create 2 to 3 centimetre-wide lines. The vertical lines correspond to the middle of the composition and highlight the slightly off-centre position of the figure’s navel (fig.30); the horizontal line marks the lower third of the figure and corresponds to the figure’s waist. As with Modigliani’s outline of the figure using a carbon-based medium in the underdrawing stages, he used these paint markings as guides for positioning the figure. This white layer seems to be the first phase of the painting process. To a certain extent, this procedure is also visible in Elvira Resting at a Table, with the main distinction being that this preliminary layer was not flattened or smoothed. As a unique and prominent feature of the Bern painting, this preliminary paint layer application appears to be an exploratory technique where Modigliani used the compressed lines of bright white, still visible in the final composition, to further highlight the figure.

Over the preliminary paint layer, the figure was executed in more fluid and medium-rich paint layers. In Standing Nude (Elvira), the smooth paint texture and fine brushstrokes used for the face contrast with the more rapidly applied and roughly textured paint used for the white cloth, the background, and the figure’s torso and hands. This contrast is less evident in the Saint Louis portrait, where accents and marbled patterns occur throughout. Thin and fluid contour lines of black paint weave under and over skin tones, indicating multiple instances of reworking in wet-in-wet technique (fig.16).

Fig.31

Amedeo Modigliani

Elvira Resting at a Table, high-resolution photomicrograph (flipped on the horizontal) of the lower left eye, showing the marbling effect of the wet-in-wet technique, captured at 35x magnification

Photo courtesy of C. Books / Photo © Saint Louis Art Museum

The fluidity of the wet-in-wet technique used in Elvira Resting at a Table is best showcased in the details: photomicrographs reveal the sophisticated blurring of boundaries Modigliani created with this effect (fig.31). He applied layers of warmer black paint over the underlying black of the hair, then over this, a paler dark grey. Highlights in the blue background were painted after the skin tones. Thicker applications of light blue and white were applied along the figure’s right shoulder and as a collar highlight using dabs and wet-on-wet technique. Purple-grey paint in the upper right of the composition was also applied with a dabbed wet-on-wet mixing. The artist signed his name in binder-rich black paint in the upper right to affirm that the painting was fully resolved.

A principal distinction between the two portraits of Elvira is the attention Modigliani paid to the figure versus the overall composition. In Elvira Resting at a Table he worked over the background, figure, chair, table and bowl of greens, and returned to the figure once more towards the final painting phase. The entirety was unified with circular, revolving attention before the artist completed the background highlights and lowlights and signed ‘modigliani’ into still-tacky paint to mark the whole rapidly painted endeavour as complete.

In contrast, Modigliani evidently laboured over Standing Nude (Elvira), largely ignoring the background once it had been set in place and returning again to build up the figure’s ruddy skin with notably less wet-in-wet technique than in Elvira Resting at a Table. The artist, in his attention to the skin tones of the figure and to the face in particular, left the hands roughly rendered – a sketchiness that emphasises the sitter’s grip on the cloth as precariously loose. The duration of each painting session and the time between sessions is difficult to determine. It is apparent that the artist did not sign the work immediately, as the signature was applied over dry paint. The rectilinear form of the writing has more in common with the way the artist signed letters using a pen than with the swirling brushwork of the Saint Louis signature.75

Conclusions

Comparative research into Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira), including the interpretation of material analyses, applied painting techniques and a re-evaluation of contextual sources, has situated the Elvira paintings more firmly among Modigliani’s later works, and more than likely within his period spent in the South of France between 1918 and 1919. That the two works feature the same model is undeniable. The alignment of painting techniques and materials with those most common among his practices in the South of France also offers evidence as to the model’s identity: the sitter is less likely the brash entertainer ‘la Quique’, whom the artist knew in Paris in 1912–14, and more plausibly the youthful model working in Cagnes-sur-Mer in 1918–19. As is often the case, this technical analysis is partial and non-definitive, and extant primary sources are limited. Nevertheless, these new findings support the most contemporaneous hypotheses on Modigliani’s artistic practice and encourage new directions for future archival and technical research.

Analytical results of the ground layers, paint layers and chosen colour palettes of both paintings align most strongly with paintings attributed to Modigliani’s periods in the South of France and Paris in 1918–19. The artist favoured using a vertically oriented, marine format strainer or stretcher, the support used in both paintings during these periods. Modigliani was known to source materials from patrons and markets where he could – practicality, driven by a war-torn Europe, can account for his variety of commercial canvases and corresponding ground layers and paints in these years. Examination of the textile supports and the results of the TCAP project strongly indicate that Modigliani also used pre-primed fabrics taken from the same canvas rolls. The matches of Standing Nude (Elvira) with other paintings of the South of France period show the potential of the TCAP method in the context of authentication and the dating of the paintings.

In the Saint Louis and Bern paintings, preliminary conclusions identify an oil medium present in the paint, which was often applied using diluted pigments and thinner brushstrokes, aligning with the paint handling most typical of Modigliani’s later works of 1918–19. The Paul Cézanne-inspired palette of warm earth tones that contrast with soft, cooling blues and greys dominant in both Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) can also be associated comfortably with the preferred palettes from his South of France and later Paris years. The use of a comparatively wide range of pigments, when compared with earlier palettes, also corresponds to these later phases. The noteworthy exception of a surprising cobalt chromite blue identified in the Bern painting calls for reinvestigation of previously analysed paintings; further research may divulge more on the use of this pigment in Modigliani’s work but also its presence in paints and paint applications in the early twentieth century.

Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) share many applied techniques. The rapid, carbon-based drawing design, as well as the contour lines painted over composition boundaries, left in reserve, are present in both paintings and align with Modigliani’s broader painting practice. Underdrawing design in both compositions prioritises the figures and is executed using long, often uninterrupted lines with few alterations. Coinciding with the minimal use of underdrawing, white ground layer was left exposed to contour forms, which were reinforced with painted black outlines – a technique common to Modigliani’s practice in the South of France. In terms of paint layers, the uni-directionally dabbed and scumbled brushwork, very thinly painted backgrounds, blocked-in planes of compositional shapes, wet-in-wet paint layering, and the use of blunt tools to scrape away paint to create heightened texture were all common techniques in his practice but were particularly prevalent during 1918–19.

While the execution of Elvira Resting at a Table presents a quintessential example of the artist’s confident, quickly executed style of painting, the techniques applied to Standing Nude (Elvira) – the thinner execution of the background, the rectilinear lines applied with a flat tool in the preliminary layers, and the painting sessions staggered from one another long enough to let the paint dry – suggest a more exploratory process. Due to the lack of documentary or archival evidence, precise dating of Elvira Resting at a Table and Standing Nude (Elvira) is not possible. Nevertheless, matching the results of this technical analysis study with paintings that are known to have been created in the South of France in 1918–19 provides a strong argument for the Elvira paintings to be dated to the same period. Furthermore, the dating of Standing Nude (Elvira) may be narrowed to 1918 according to Anna Zborowska’s memoir, which places Elvira modelling for the painting between April and November of 1918 – after Modigliani travelled to the South of France and before Zborowska returned to Paris. Zborowska describes the painting in acute detail and her description aligns strongly with both the approximate age and distinct personality of the figure captured.

Although the repeated use of the same model is not novel for Modigliani – Jeanne Hébuterne, for instance, is depicted numerous times – the subtle adaptations that Modigliani made between the two Elvira paintings is noteworthy: they highlight the artist’s free experimentation, which was encouraged by the use of the same model. Differences observed in the paintings also suggest that the artist’s painting technique depended not only on the material available but also the particularities of the sitting – the model’s experience of posing and the artist’s act of capturing her. For the clothed figure, he painted confidently and fluidly, polishing off the languid posture, expressive background and aloof countenance with seeming ease. The composition of the undressed figure was completed in more thinly painted layers that were allowed to dry or semi-dry between painting sessions, capturing not a sultry nude but a bold and arrested youth. These portraits are now more soundly situated between Modigliani’s early Parisian years – those that featured either provocative poses or, in the case of associates and friends, conservative dress – and his later Parisian portraits of women attired in modern fashion. Modigliani’s portrayal of Elvira frees her of any constrictive signifiers of status in dress or salacious frivolity by humanising her in her individuality.