Germaine Richier, Chessboard, Large Version (Original Painted Plaster) 1959. Tate. © The estate of Germaine Richier.

The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

11 rooms in In the Studio

Survey the impact of the catastrophic events of WWII on the art that followed

One of the fundamental questions for artists in the middle of the twentieth century was how to continue making art after the catastrophic events of the Second World War.

The Second World War signalled a violent upending of the social and political order. Cities were reduced to rubble, millions of people became refugees and the Nazi concentration camps fundamentally changed ideas about humanity’s capacity for evil. The use of nuclear weapons revealed the possibility of further, unparalleled levels of destruction.

Across the globe, artists felt compelled to respond, both to the war and to the regional conflicts and crises that continued to erupt. Some rejected the European high cultural tradition that now seemed tainted and took inspiration from non-Western art forms or the freedom of children’s drawings. In the United States, a new form of abstract art developed, characterised by seemingly spontaneous mark-making. Others experimented with unconventional materials like tar, soil and burnt plastic, seeking new ways to express the fragility of culture and nature.

Scars, scratches, drips and heavily textured surfaces emphasise the physical act of making the work, and with it, the artist’s presence in the world. When they represented the human figure, these artists didn’t aim to create a likeness, but instead sought to capture the essence of humanity. Some artists removed people entirely, using gestural marks to suggest landscapes, nature and architecture.

The unconventional organisation of works in this room was inspired by one of the landmark exhibitions of the period, International Experimental Art at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam in 1949 which included works by Constant and Karel Appel, among others.

Curated by Kerryn Greenberg and Matthew Gale

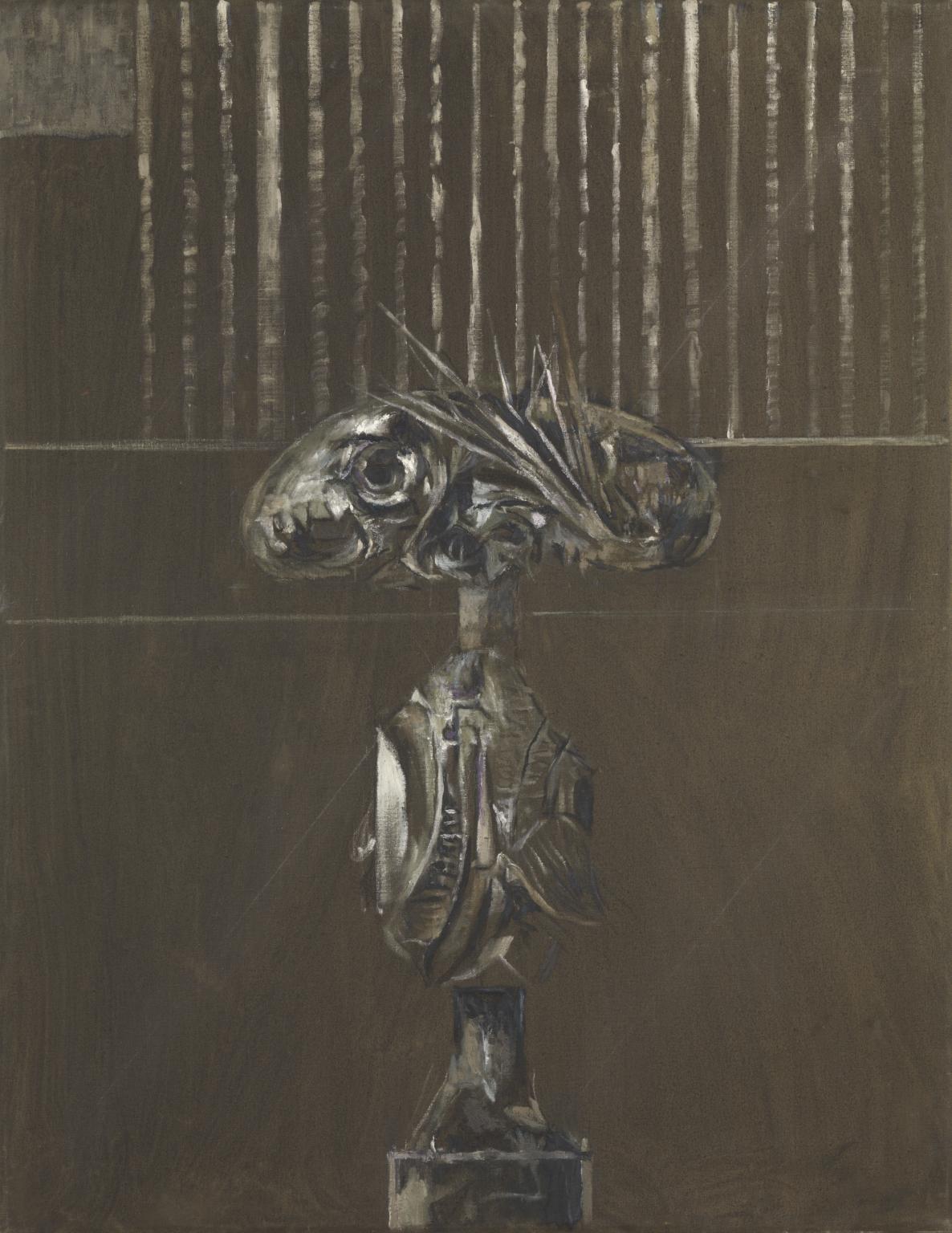

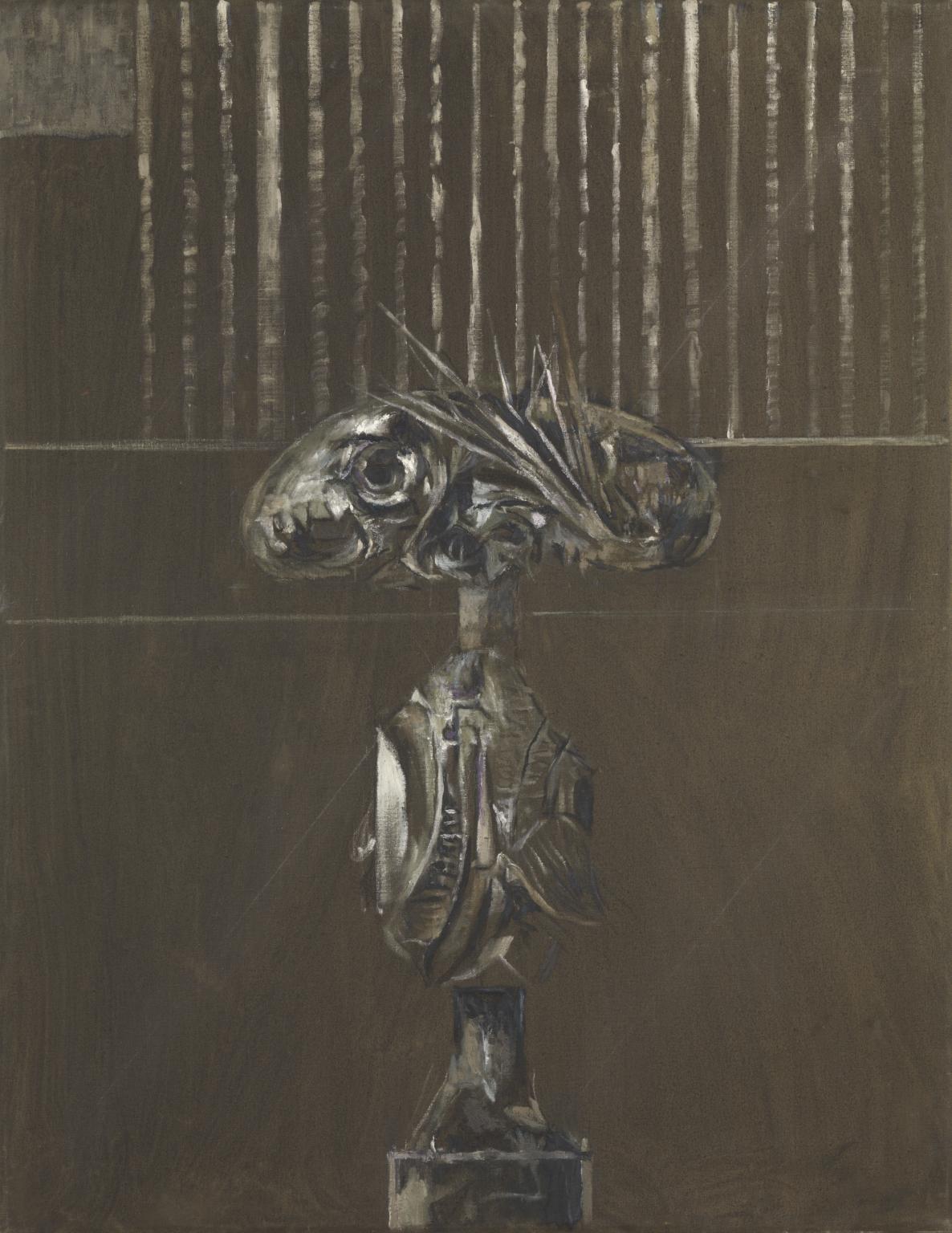

Graham Sutherland OM, Head III 1953

Insects and fossils merge in Sutherland’s Head III. The painter would later insist that these hybrid creatures were not intended to be threatening. At the time, however, the critic Herbert Read identified in Sutherland’s work ‘the now prevailing cosmic anxiety’.

Gallery label, October 2016

1/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Pierre Soulages, Painting, 23 May 1953 1953

Soulages titled this painting with the date he finished it. He had started using heavy brushstrokes of black paint against a light background in 1947. His style became more energetic and gestural throughout the 1950s. Soulages has said that for him abstraction is a way to explore his imagination and inner experience. 'I work, guided by inner impulse, a longing for certain forms, colours and materials,' he explained in 1950. '[I]t is not until they are on the canvas that they tell me what I want'.

Gallery label, June 2020

2/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Nicolas de Stael, Marathon 1948

De Staël’s paintings emphasise the physical nature of their surfaces. Here he appears to have painted on the front side of a piece of printed fabric. It is possible that he took the fabric’s pattern as his starting point. His typically energetic work is seen at its most explosive here. De Staël explored several sporting themes in his work. He titled this Marathon, perhaps reflecting on his own long, hard struggle to develop a personal artistic style.

Gallery label, June 2020

3/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Zao Wou-ki, Before the Storm 1955

As a student in Hangzhou, China, Zao became interested in the European art scene. He moved to Paris in 1948 and immersed himself in the work of the artists who lived there. His own distinctive style emerged in the mid-1950s, drawing upon both Eastern and Western artistic practices. Before the Storm belongs to a group of artworks by Zao, often referred to as the Oracle Bone series. The pieces include characters from an ancient form of Chinese calligraphy known as ‘oracle bone script’. Zao reconciled this tradition with contemporary artistic concerns to establish a personal language of abstraction.

Gallery label, January 2022

4/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Sorry, no image available

Jean-Michel Atlan, Baal the Warrior 1953

Baal (or Ba’al), the god of storms and skies, was worshipped in ancient Egypt (c.1543–1292 BC). He is traditionally depicted as a powerful warrior. Here a figure stands with his left arm raised, perhaps holding a thunderbolt. The triangle at the lower left corner alludes to Egyptian pyramids. Atlan started painting in Paris during the Second World War. He was Jewish and Algerian, and a member of the French Resistance against the German occupation. When he was arrested by the Nazis, he pretended to be experiencing mental health problems to avoid being sent to a concentration camp. He was confined to a psychiatric hospital for two years.

Gallery label, June 2020

5/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Ferdinand Kulmer, Brown Picture 1960

Kulmer was part of a generation of painters in Croatia (then part of Yugoslavia) working with gestural abstraction. This style of painting is known for its free sweeping brush strokes. Kulmer maintained a link to experience and reality in his work. The heavily worked surface of this painting was his response to the ‘climate of the forest’. It was included in Contemporary Yugoslav Painting and Sculpture at Tate in 1961. The exhibition was part of a wider cultural effort to signal Yugoslavia’s independent political position at a moment of increased tension in the Cold War.

Gallery label, June 2021

6/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Prunella Clough, Rockery, 1963 1962–3

Clough described her use of colour as ‘muffled, tonal, and murky’. Here, as the title suggests, she depicts a garden in which plants grow among heaped, rough stones. Clough became known as an abstract painter, but she saw her ‘subject matter mainly as landscape’. However, it was the feeling, not just the look of a place that mattered to her. She walked through the landscapes she wanted to paint, explaining: ‘the sense of place is crucial for me and involves sensations other than the purely optical ones of observation’.

Gallery label, June 2020

7/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

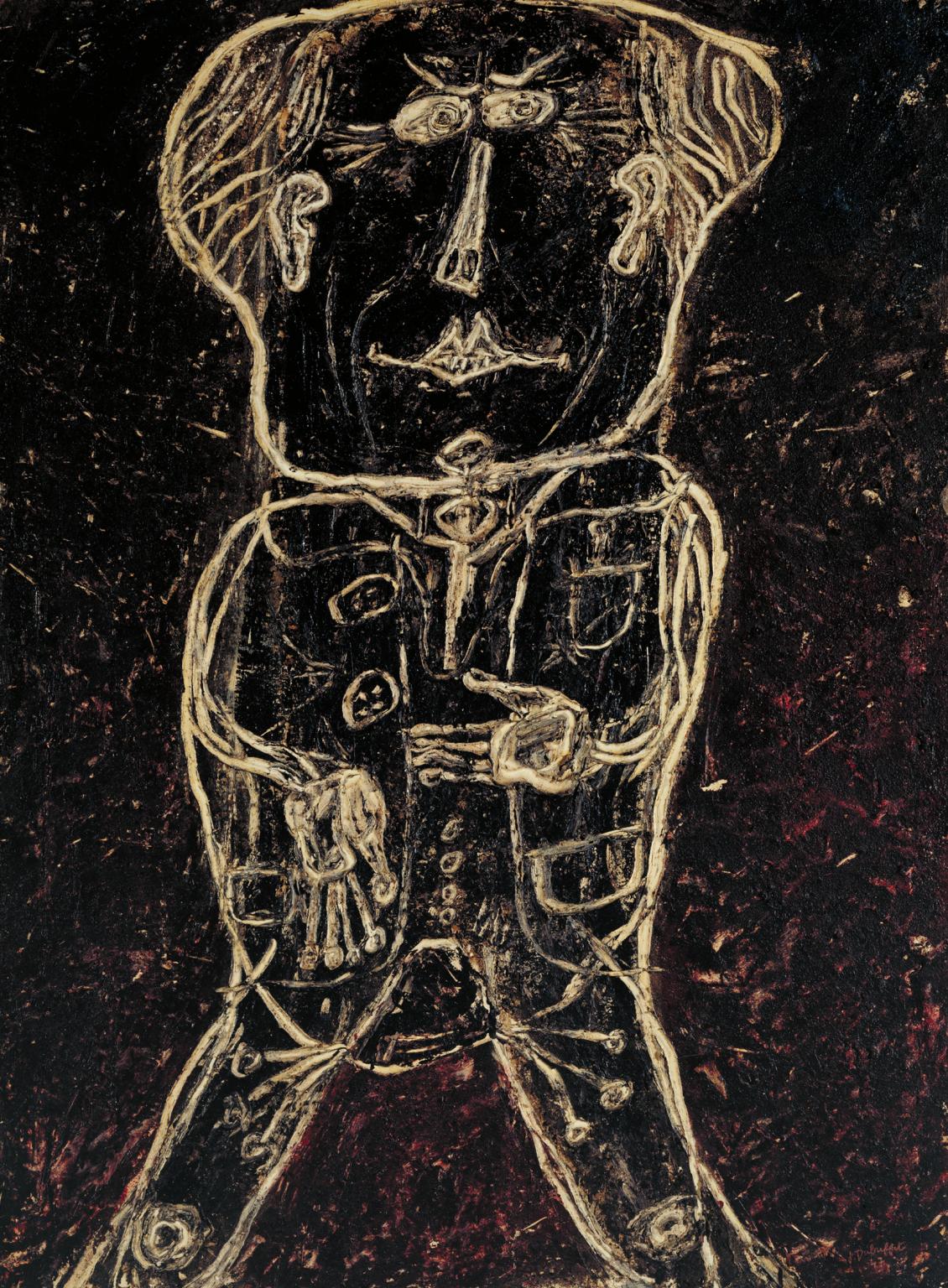

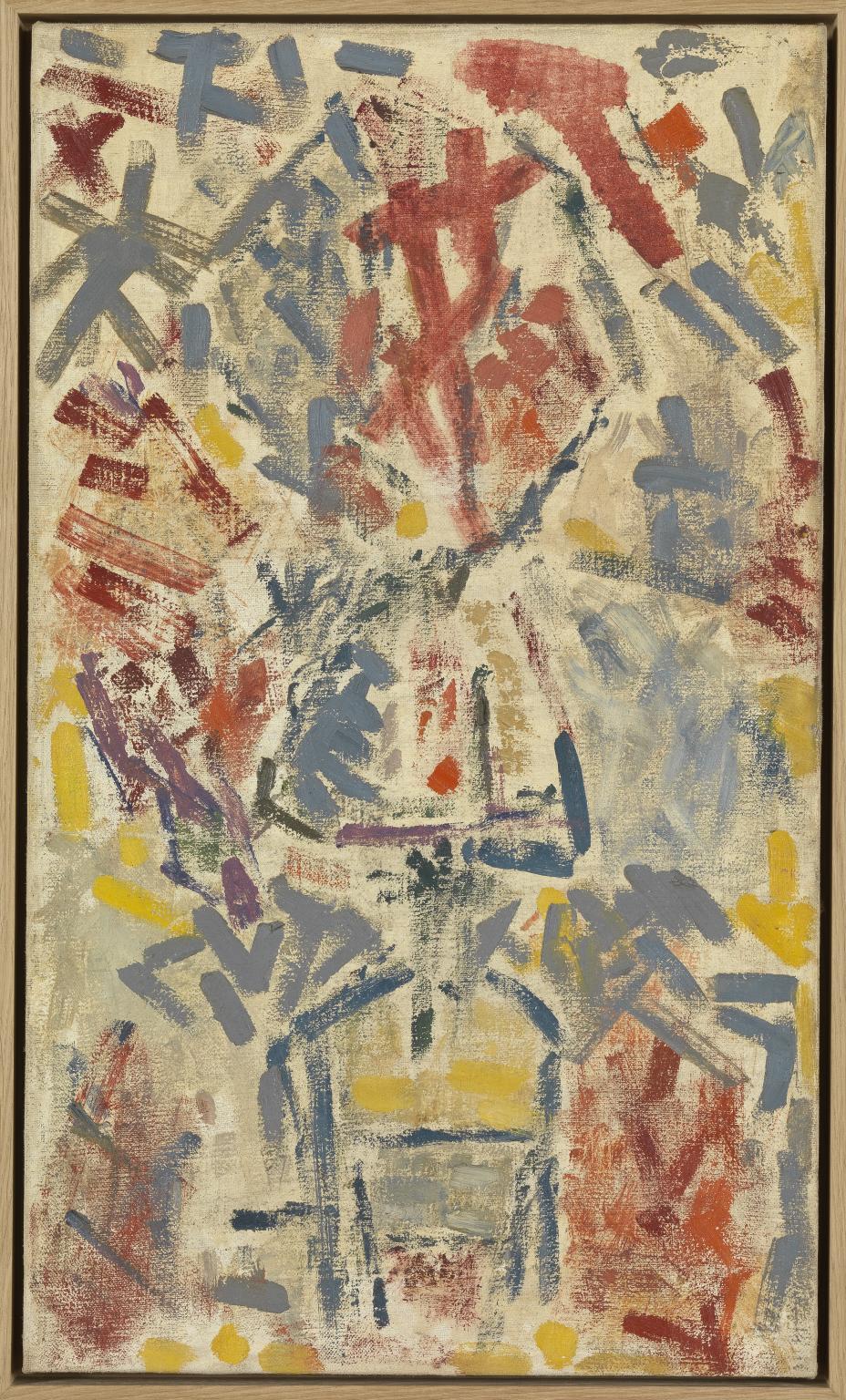

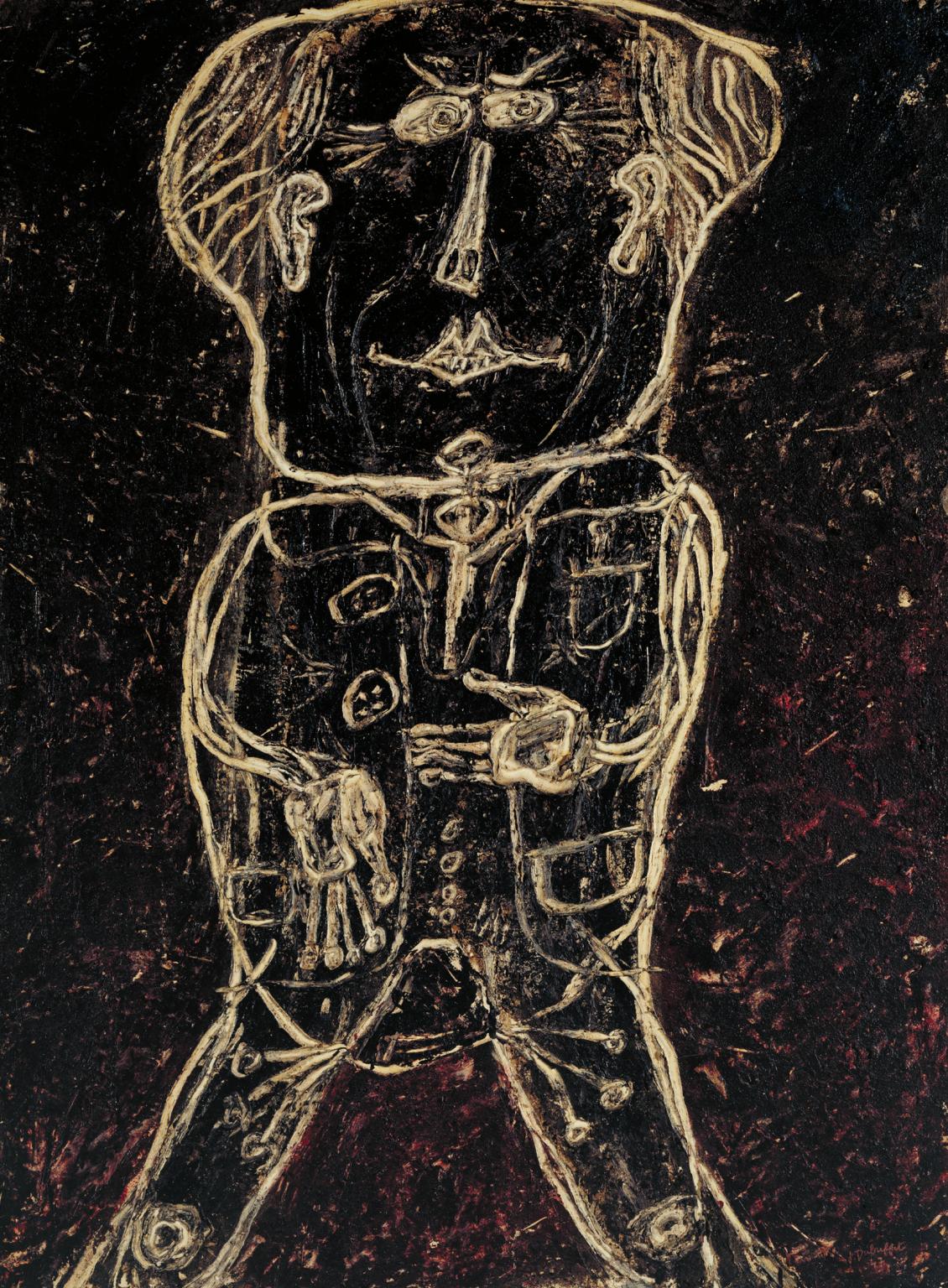

Jean Dubuffet, Monsieur Plume with Creases in his Trousers (Portrait of Henri Michaux) 1947

Dubuffet roughly scraped the outline of a figure into thick paint. The face and body are scarred and crumpled. It is one of a group of unusual portraits Dubuffet made of his artistic and literary friends. This is the poet-painter Henri Michaux. His writings featured ‘Monsieur Plume’, a semi-autobiographical comic character. Dubuffet painted him as this alter ego.

Gallery label, June 2020

8/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

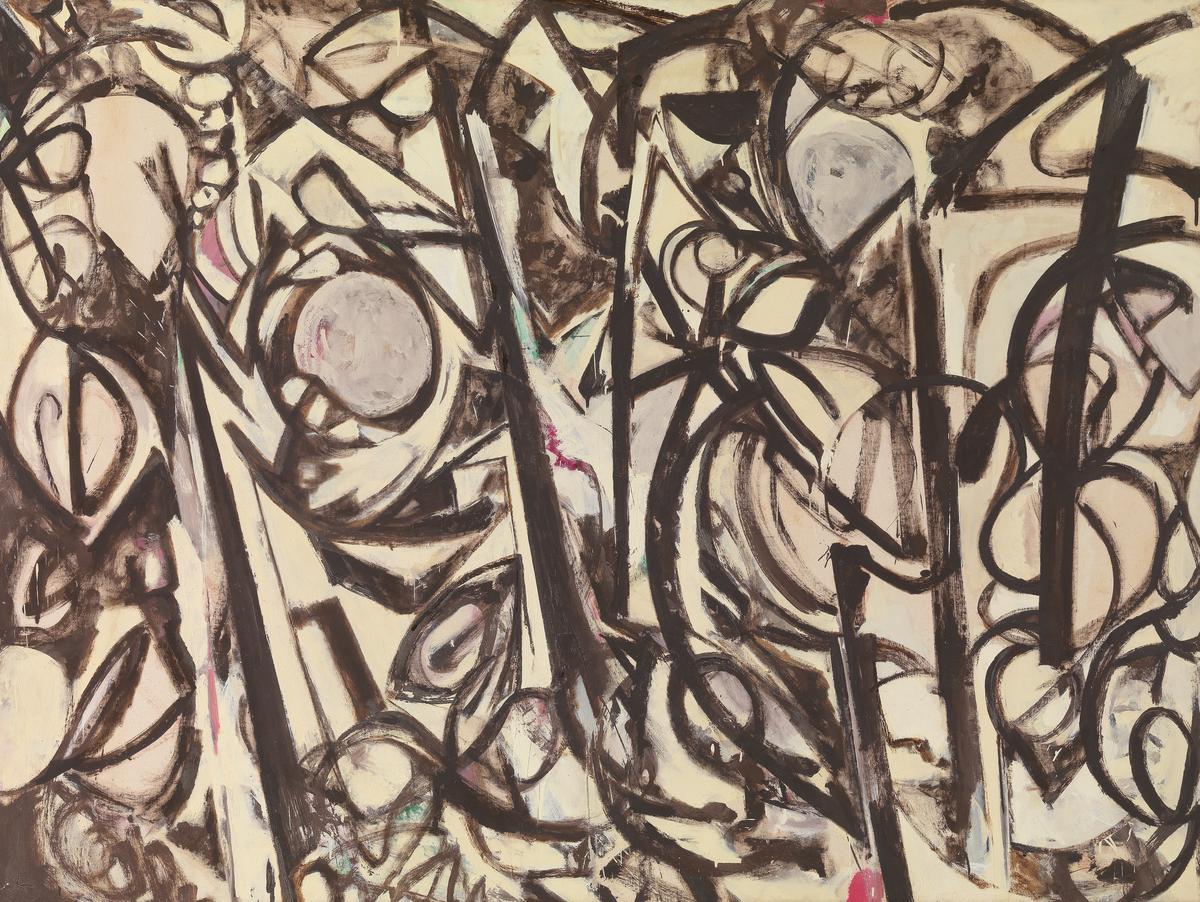

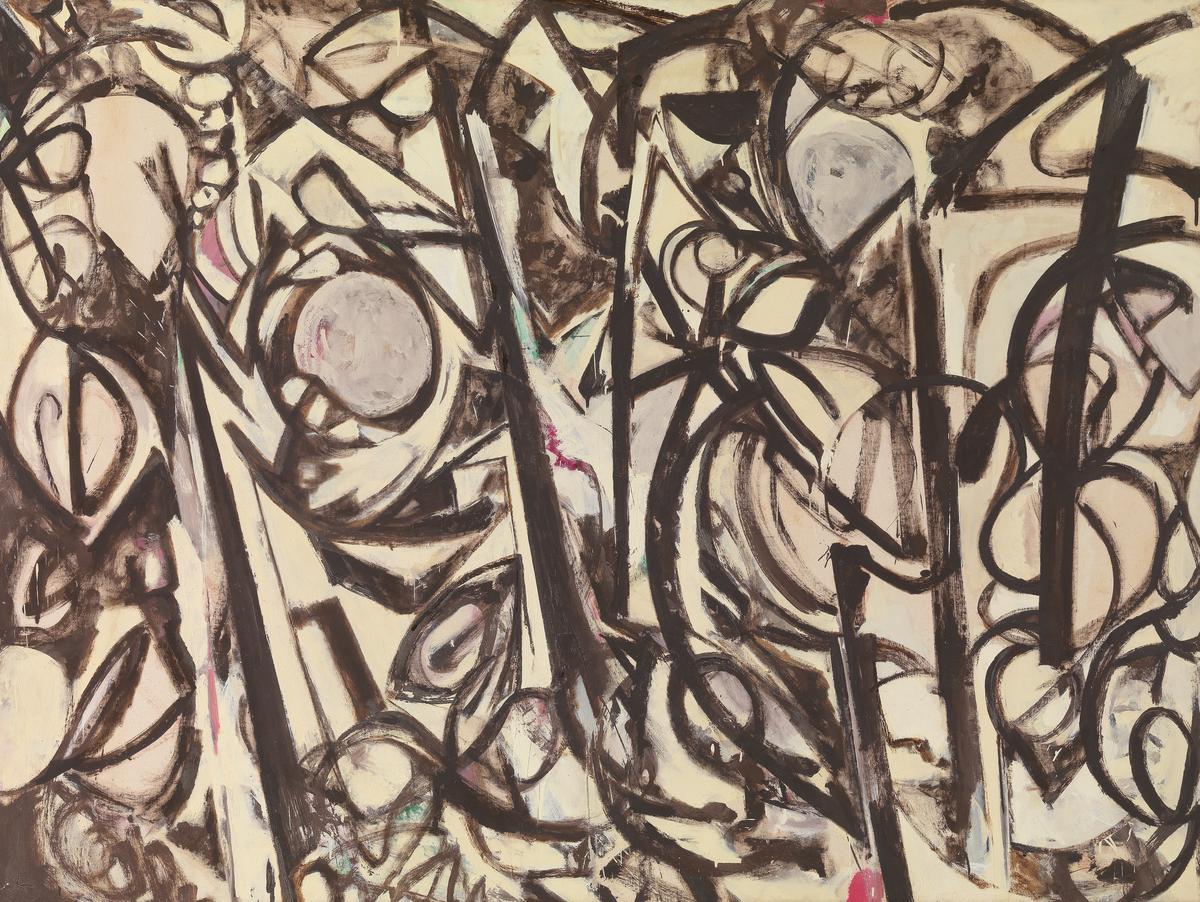

Lee Krasner, Gothic Landscape 1961

Although this is an abstract painting, the thick vertical lines that dominate its centre can be seen as trees, with thick knotted roots at their base. It was probably this that led Krasner to call the painting Gothic Landscape, several years after completing it. Krasner was married to the artist Jackson Pollock. Gothic Landscape was made in the years following his death from a car crash in 1956. It belongs to a series of large canvases whose violent and expressive gestural brushstrokes can be read as a reflection of her grief.

Gallery label, August 2019

9/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

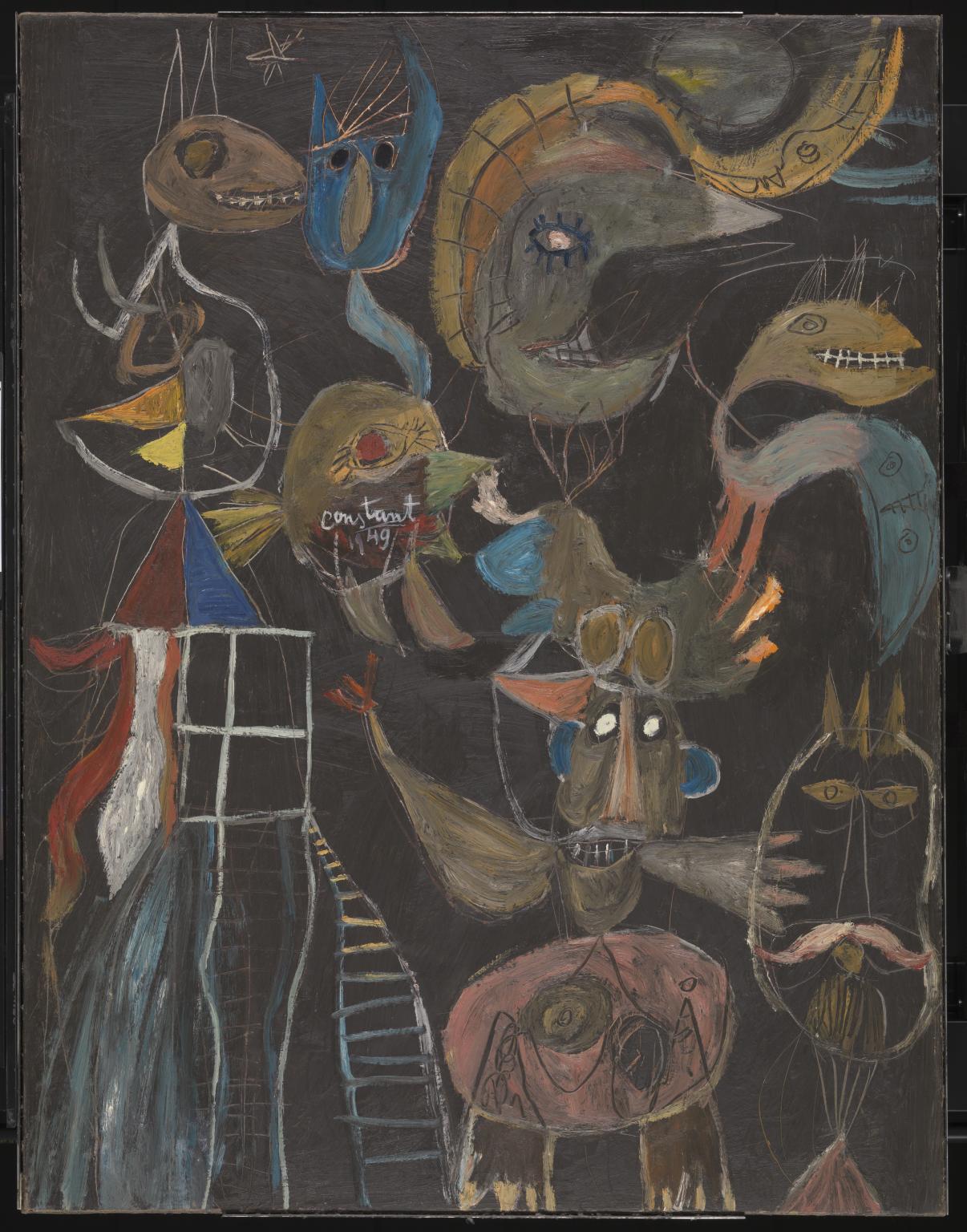

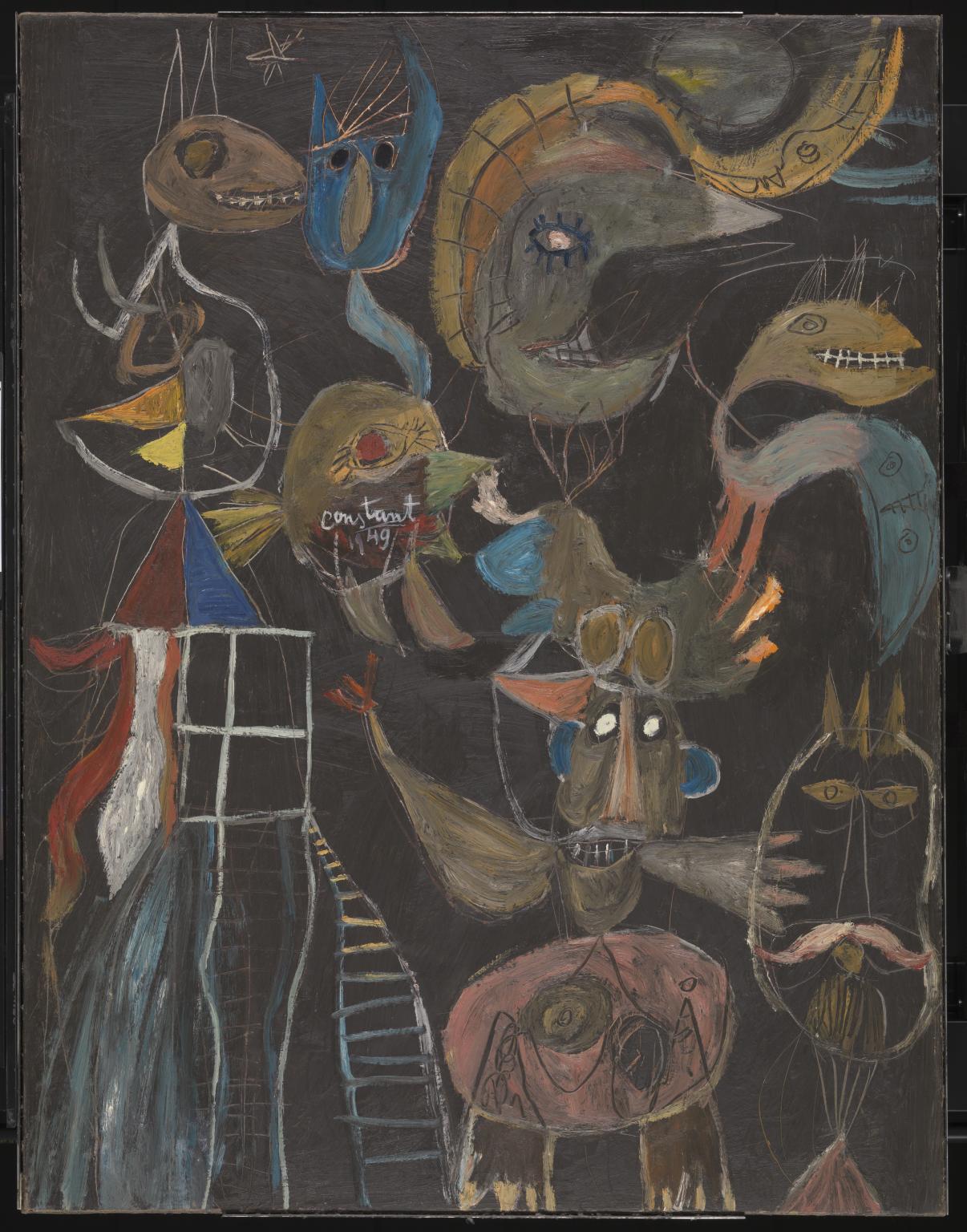

Constant (Constant A. Nieuwenhuys), After Us, Liberty 1949

Constant believed that spontaneity and free expression could transform culture. He was fascinated by the uninhibited art of children and untrained artists. The wild figures here are a mixture of human and animal. Real and imagined animals feature in many of Constant’s works. He kept dogs, cats, a baboon and an iguana as pets, and was a frequent visitor the Amsterdam zoo. Originally this work was called ‘To Us, Liberty’. Constant retitled it to reflect his ‘doubts about the possibility of “free art" in an unfree society’.

Gallery label, June 2020

10/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Jackson Pollock, Number 14 1951

By 1951, Pollock had achieved considerable success with his dripped and poured abstract painting. He was widely regarded as the leading young North American artist. Perhaps fearing that he was reaching a dead-end in his work, he embarked on a series of black and white paintings in which figures emerge, as they had in his early works. After rolling the canvas out on the floor, he would apply the paint – usually industrial enamel paint – with sticks and basting syringes. The artist Lee Krasner, who was married to Pollock, recalled him wielding these ‘like a giant fountain pen’.

Gallery label, October 2019

11/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Karel Appel, Hip, Hip, Hoorah! 1949

The title of Hip, Hip, Hoorah! was intended to celebrate the artistic freedom achieved by the CoBrA movement (1948–1951). This was a group of artists active in Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam who sought to revive culture after the Second World War. The figures combine human elements with animal or bird-like features. Appel thought of them as ‘people of the night’, and so gave them a dark background. The bright colours and child-like imagery are typical of CoBrA. Appel often took inspiration from children’s drawings. He believed ‘the child in man is all that’s strongest, most receptive, most open and unpredictable’.

Gallery label, June 2020

12/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

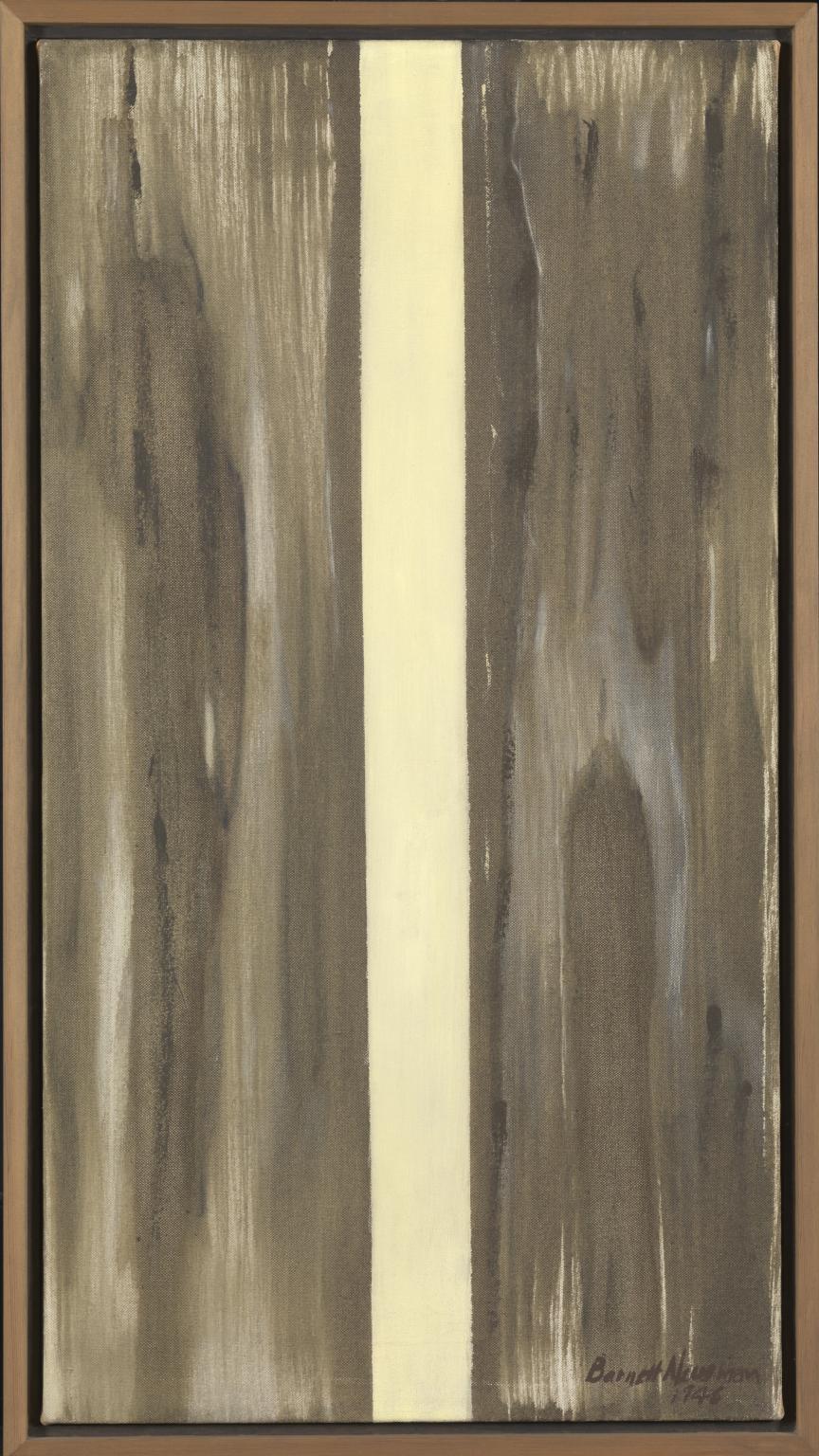

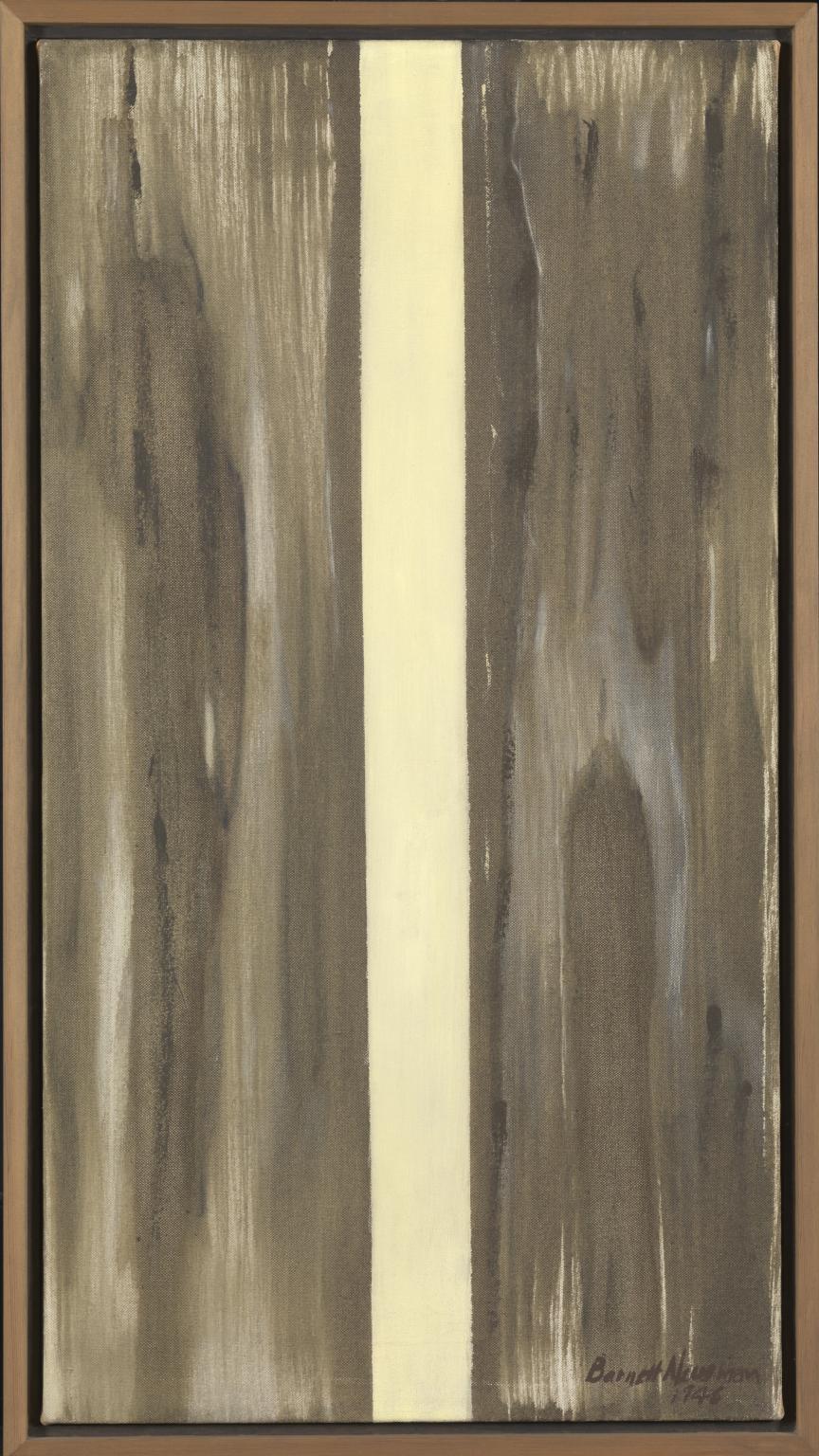

Barnett Newman, Moment 1946

Moment is one of Newman’s first paintings to include a vertical band of light. He called this a ‘zip’. The title refers to the moment of creation. He said that in these early works he was manipulating colour and space to fight the chaos that existed before the beginning of the universe. It might also be a moment of arrival for art. Newman was among the artists who developed abstract expressionism in the 1940s and 1950. The movement was characterised by the impression of spontaneous mark making.

Gallery label, June 2020

13/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

William Gear, The Sculptor 1953

This work can be read as a figure, with strut-like legs rising from the lower edge and an insect-like head in the top right. Gear was working on ideas for a sculpture at the same time as painting this. A new angularity and sharpness had entered his work in the 1950s. This has often been connected to the feeling of anxiety that emerged in British art – particularly sculpture – after the Second World War. But Gear himself rejected the ‘the stupid small-time … talk about Zeitgeist and angst and fears' in relation to his work.

Gallery label, June 2020

14/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Carl Buchheister, Composition Kolvil 1960

Buchheister’s artist style changed radically after the Second World War. Before the advent of National Socialism in Germany he made linear abstract works. After a long interruption in his career he returned to art after the war. In his later years he worked in a much freer style, principally on paper, incorporating more varied materials and textures.

Gallery label, October 2016

15/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

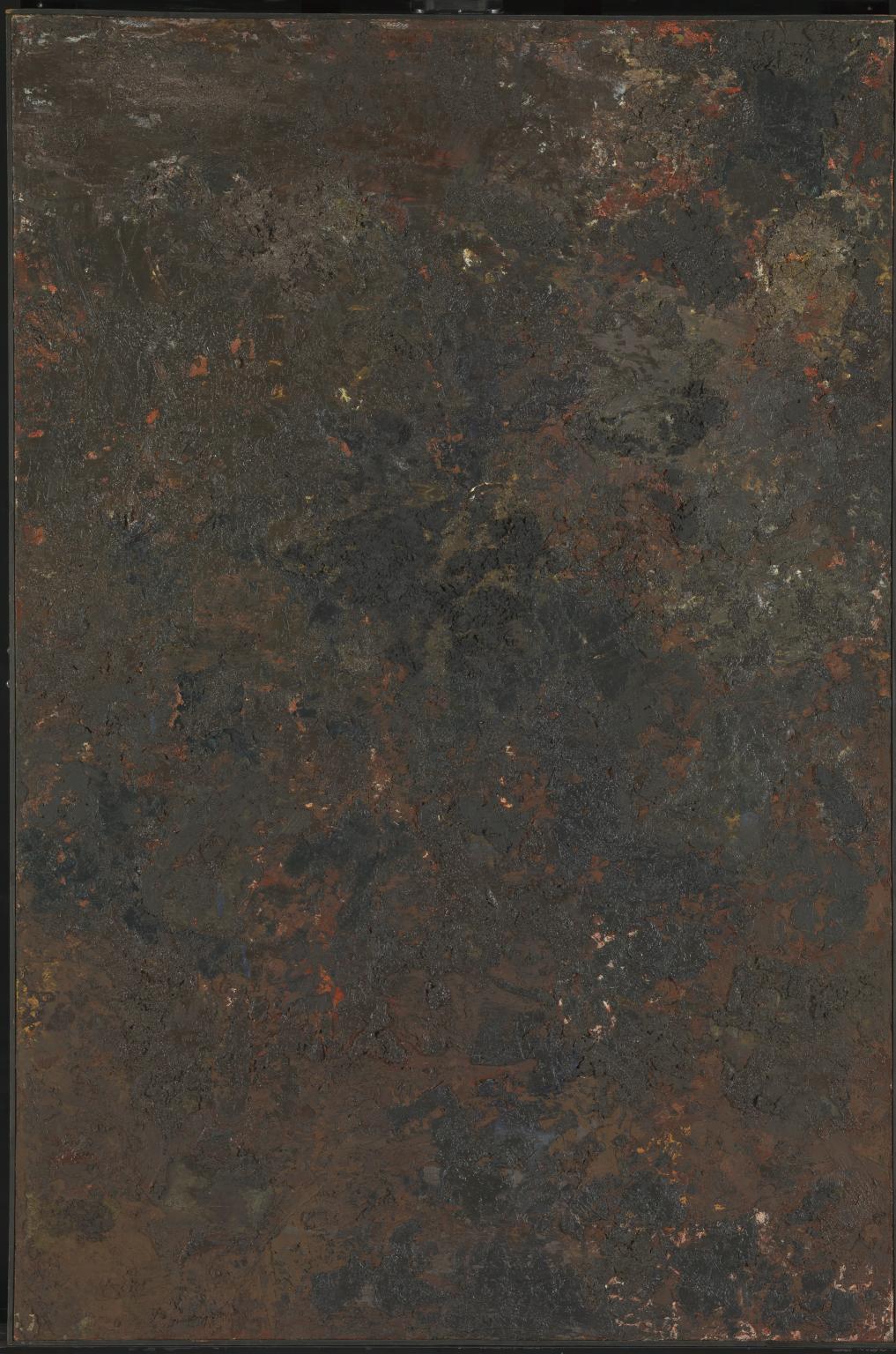

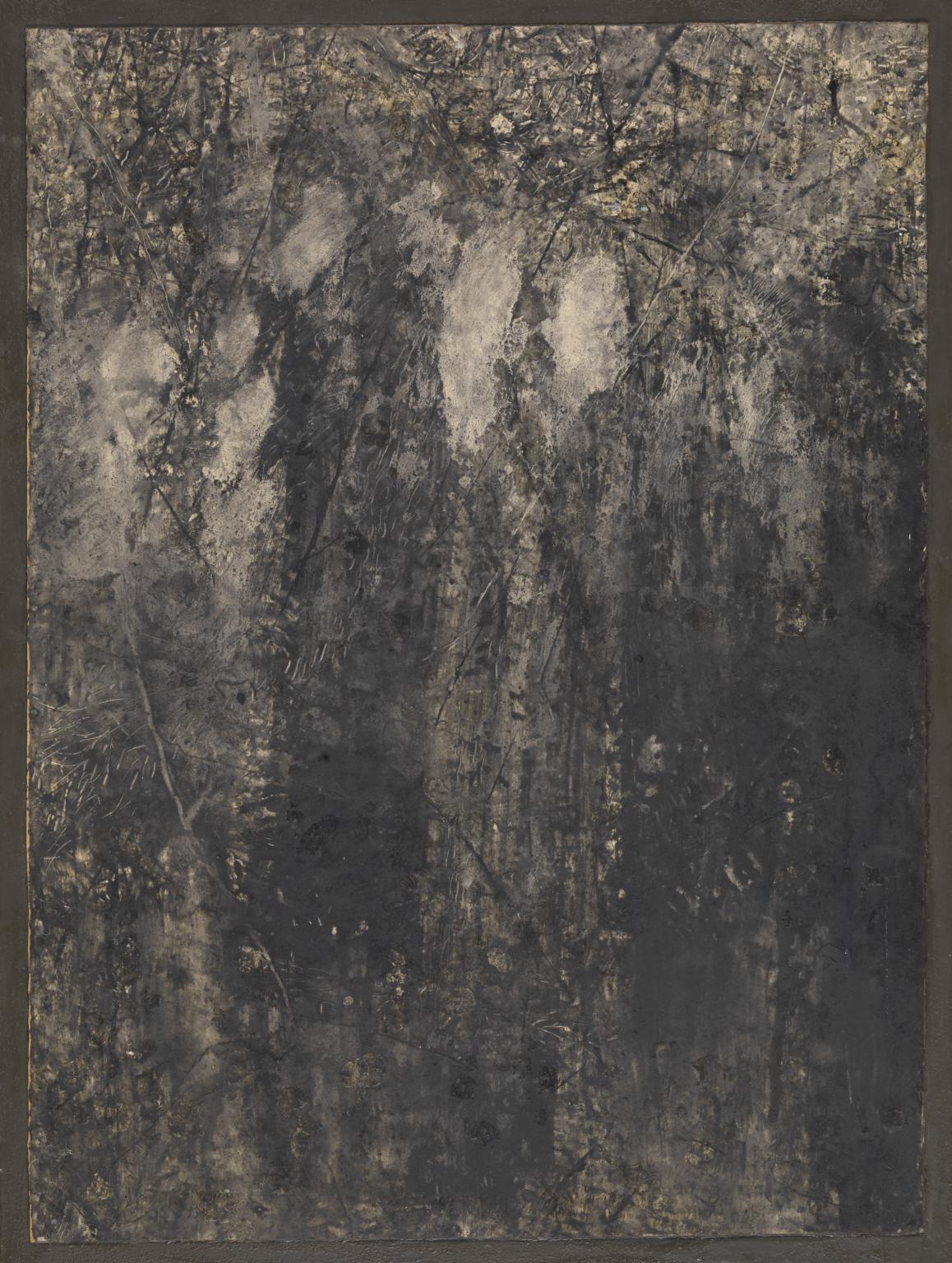

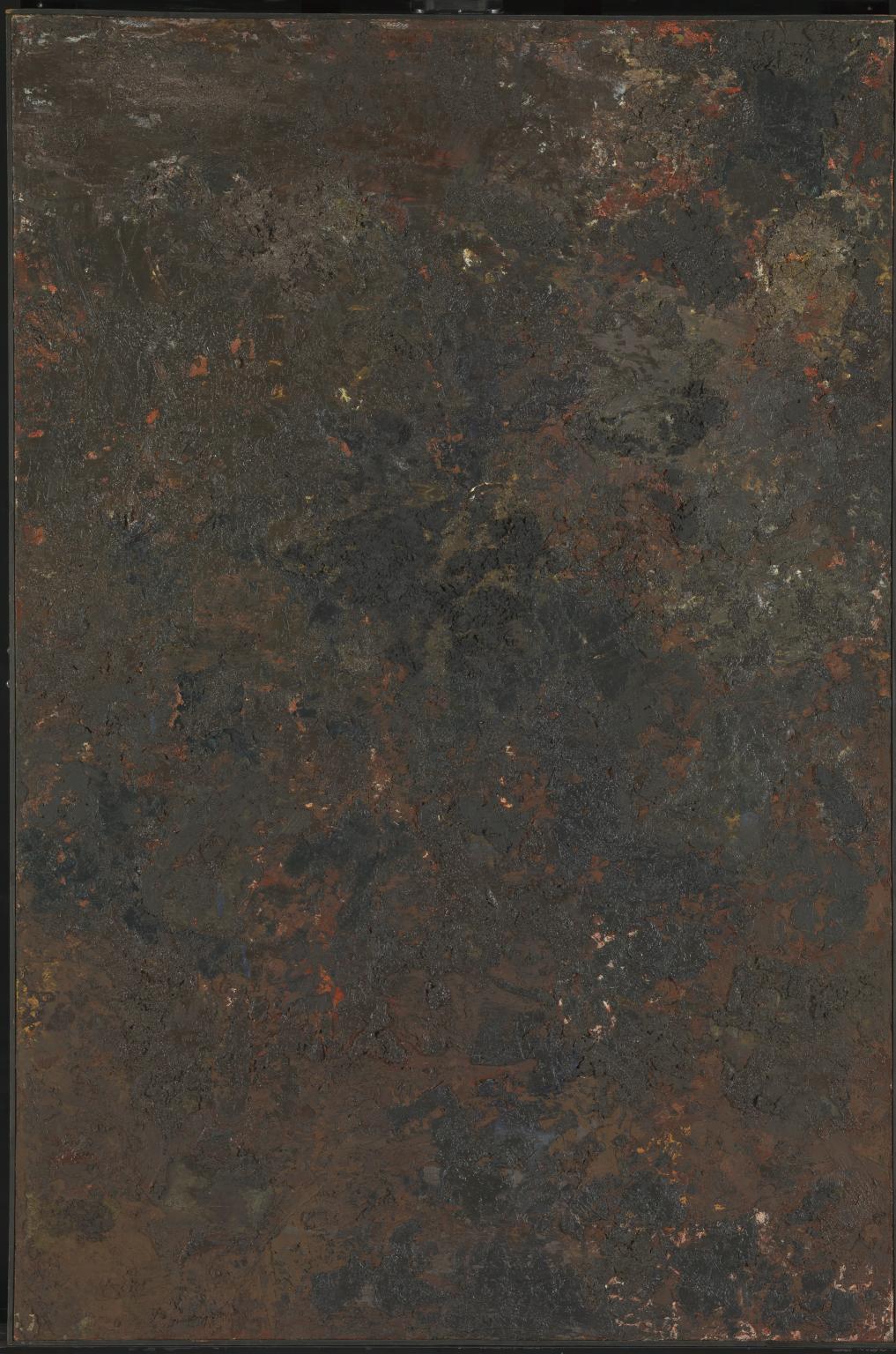

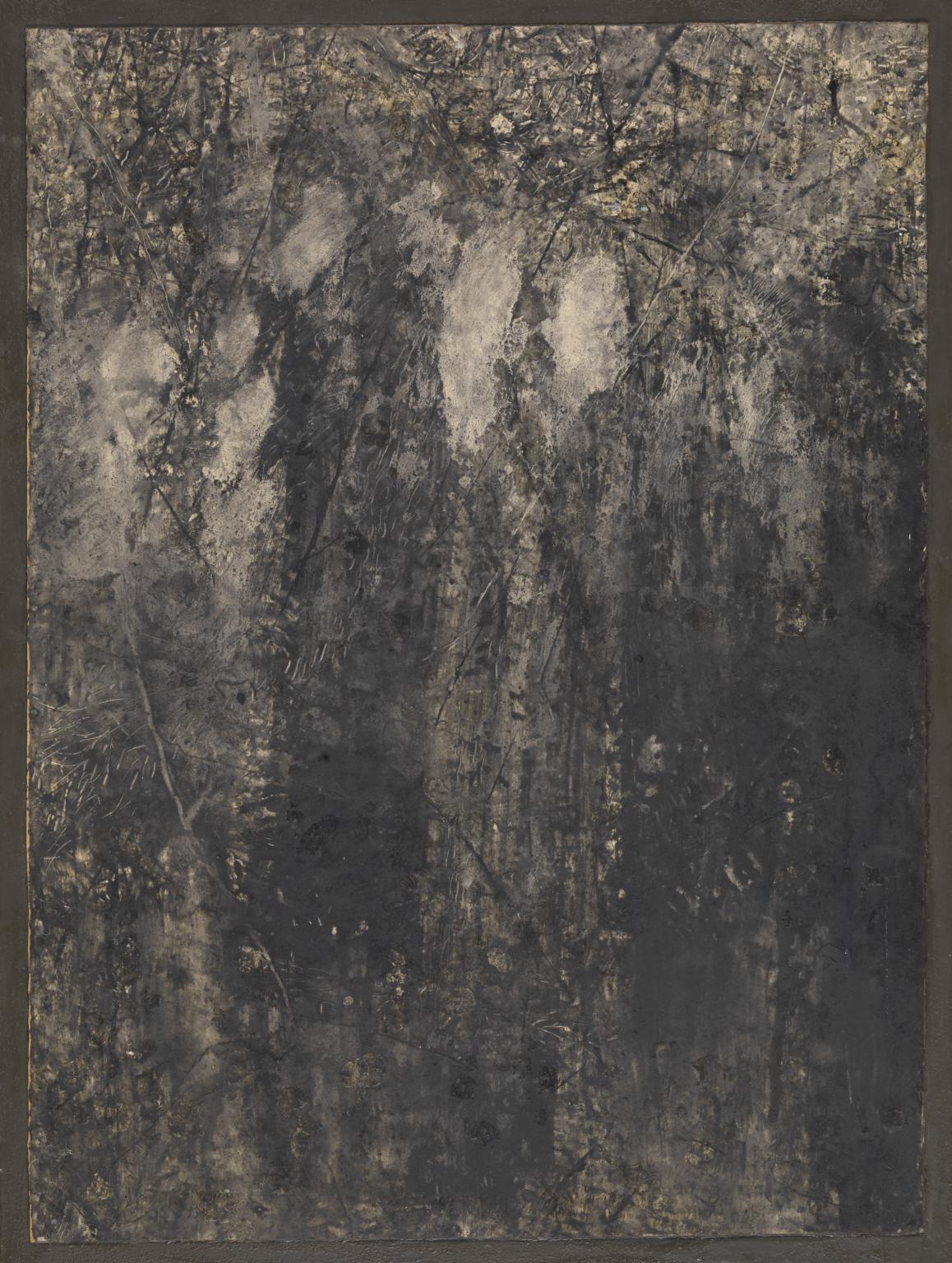

Judit Reigl, Guano 1958–62

Reigl put a canvas on the floor of her studio and let paint from works-in-progress fall onto it. This build-up of paint became compacted and developed an extraordinary crust. This created a surface made by chance. Reigl then reviewed it, scraping back the paint and reworking areas. The title, Guano, refers to the faeces of seabirds and bats. Horizontal furrows mark the surface. These might suggest archaeological layering. The textures also evoke urban sites, from modern pavements to ancient walls. This creates a sense of an embedded history in the work.

Gallery label, June 2020

16/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Shafic Abboud, Composition c.1957–8

In Composition Abboud used thick paint, applied with a palette knife. The irregular grid gives the work a sense of movement. It is characteristic of his abstract work of the 1950s. At that time he was living in Paris, but the painting carries memories of the light and colours of Lebanon, where Abboud was born. There may even be the suggestion of an aerial view of rural landscape. He wrote: ‘I like pursuing the work up to the abstract picture without letting go of the real origin’.

Gallery label, June 2020

17/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Reborn Sounds of Childhood Dreams I 1961–5

El-Salahi studied painting in Khartoum, Sudan, in the late 1940s. He then completed his studies in London. When he returned to Sudan in 1957 it was a newly independent country in the middle of a civil war. El-Salahi recognised that this new context required a different artistic approach. He started using simple forms, strong lines and sombre colours. He was inspired by his environment and included Arabic and African forms and iconography. In this work El-Salahi captures the moments when memory and dreams, past and present collide.

Gallery label, June 2020

18/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

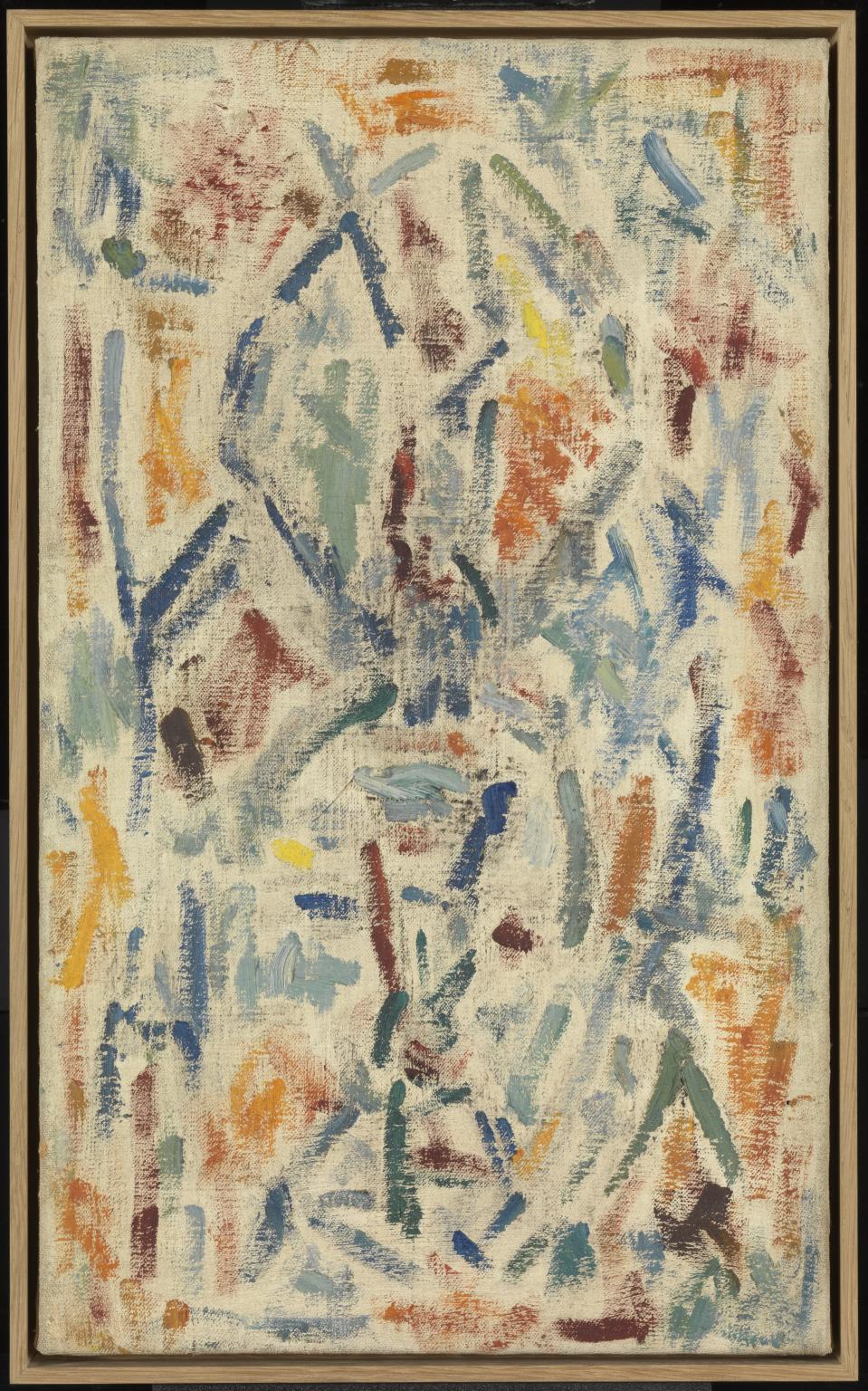

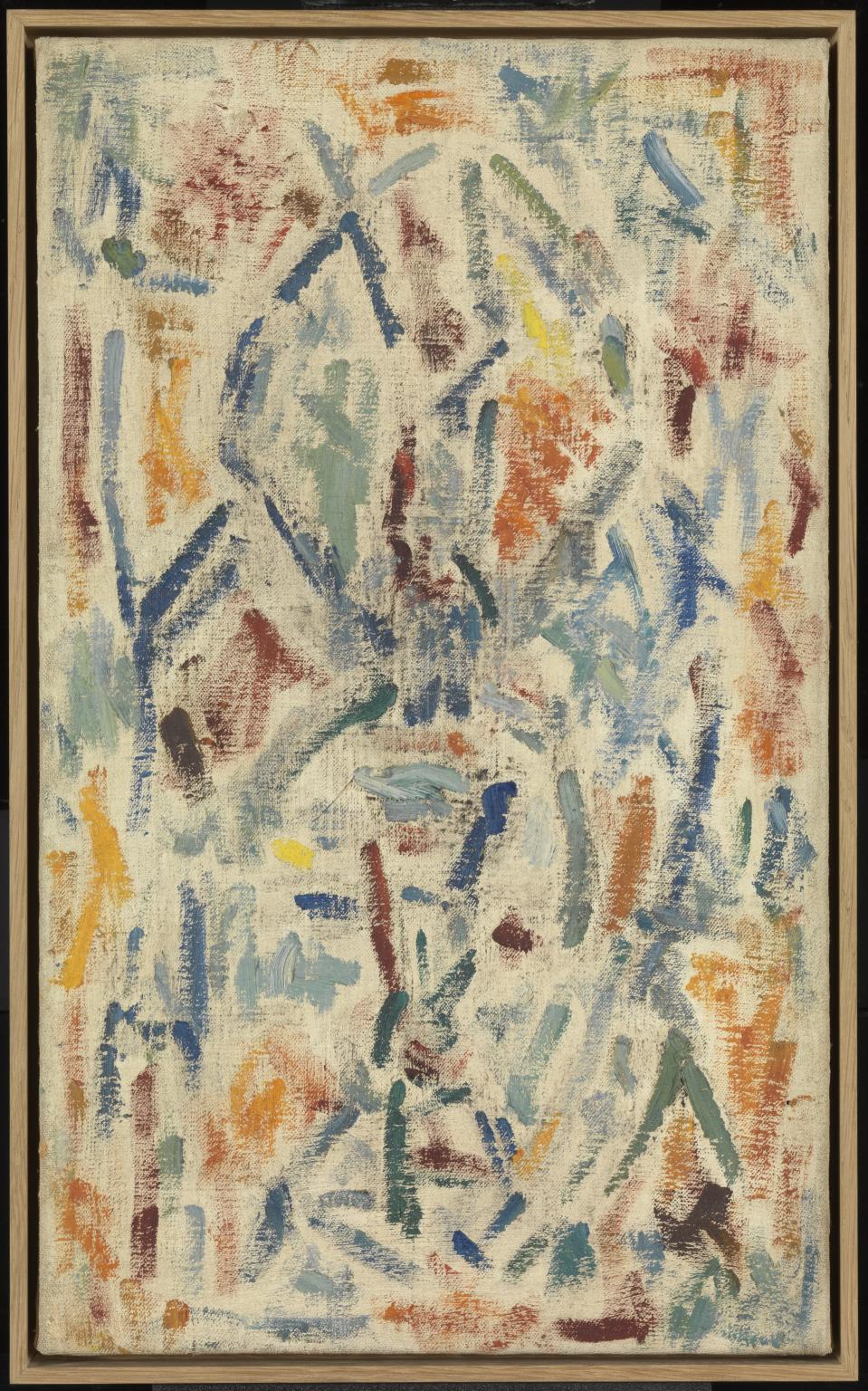

Ernest Mancoba, Untitled 1957

Mancoba believed in the importance of spontaneity and freedom of expression. His bold colours and dynamic gestures reveal his painting process. He said, ‘In my painting, it is difficult to say whether the central form is figurative or abstract. But that does not bother me.’ Born in Johannesburg, Mancoba left for Paris in 1938. He moved to Copenhagen after the Second World War. There he became one of the founding members of CoBrA, an artist group whose expressionistic painting style was inspired by the art of children. He returned to Paris in 1952, where he lived until his death.

Gallery label, August 2019

19/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Ernest Mancoba, Untitled 1957

Mancoba believed in the importance of spontaneity and freedom of expression. His bold colours and dynamic gestures reveal his painting process. He said, ‘In my painting, it is difficult to say whether the central form is figurative or abstract. But that does not bother me.’ Born in Johannesburg, Mancoba left for Paris in 1938. He moved to Copenhagen after the Second World War. There he became one of the founding members of CoBrA, an artist group whose expressionistic painting style was inspired by the art of children. He returned to Paris in 1952, where he lived until his death.

Gallery label, August 2019

20/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Hamed Abdalla, Defeat 1963

Abdalla experimented with unusual materials and techniques. He made Defeat by overlaying silver leaf with aluminium. He then used a blowtorch to burn areas on the bright surfaces. Marks resembling writing overlay the composition. He made these with a combination of black paint and tar. Abdalla moved from Egypt to Denmark in 1957 and later lived in France. But he remained engaged with political developments in his home country. Much of his work reflects on political failure and the impact of conflict.

Gallery label, June 2020

21/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

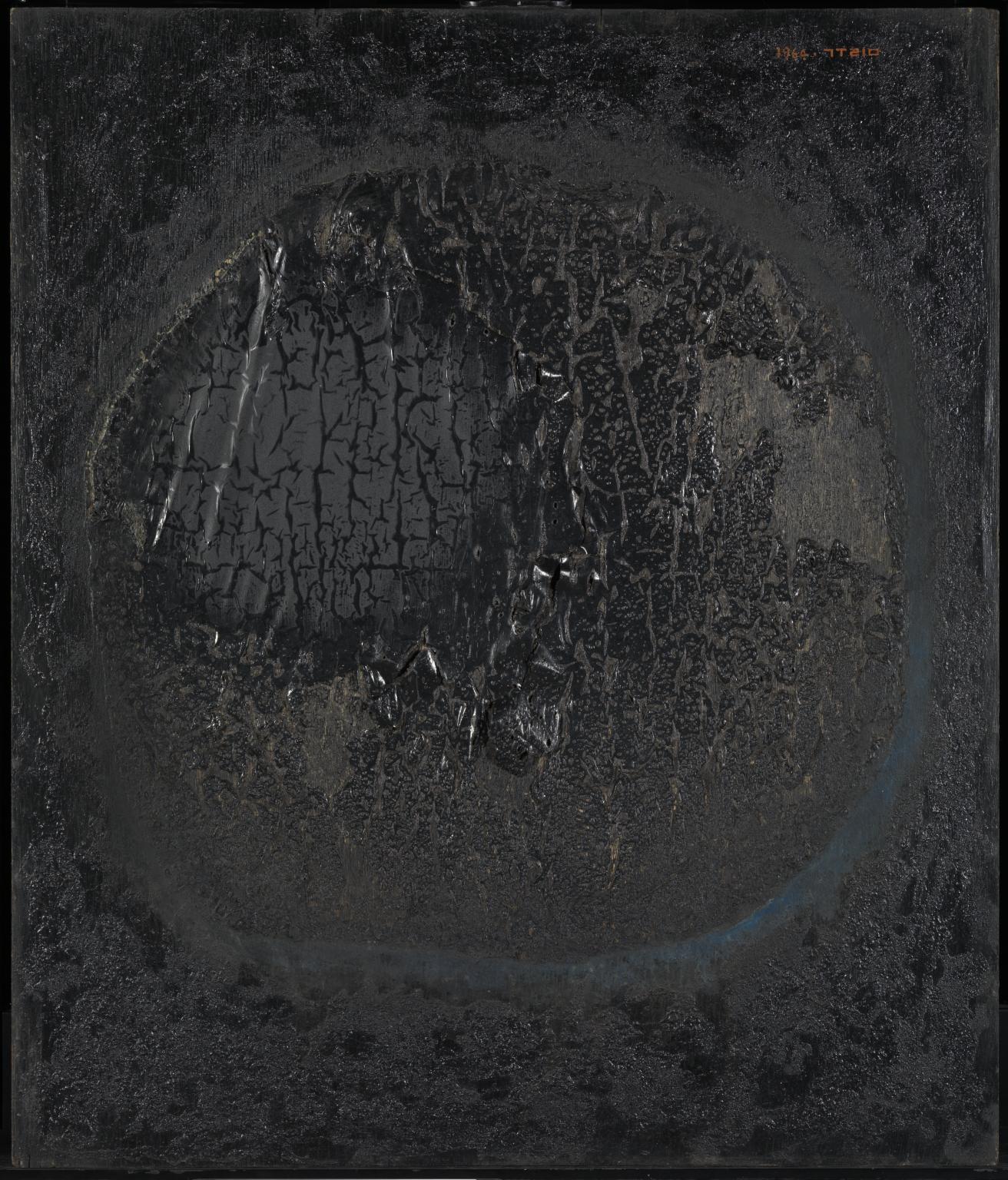

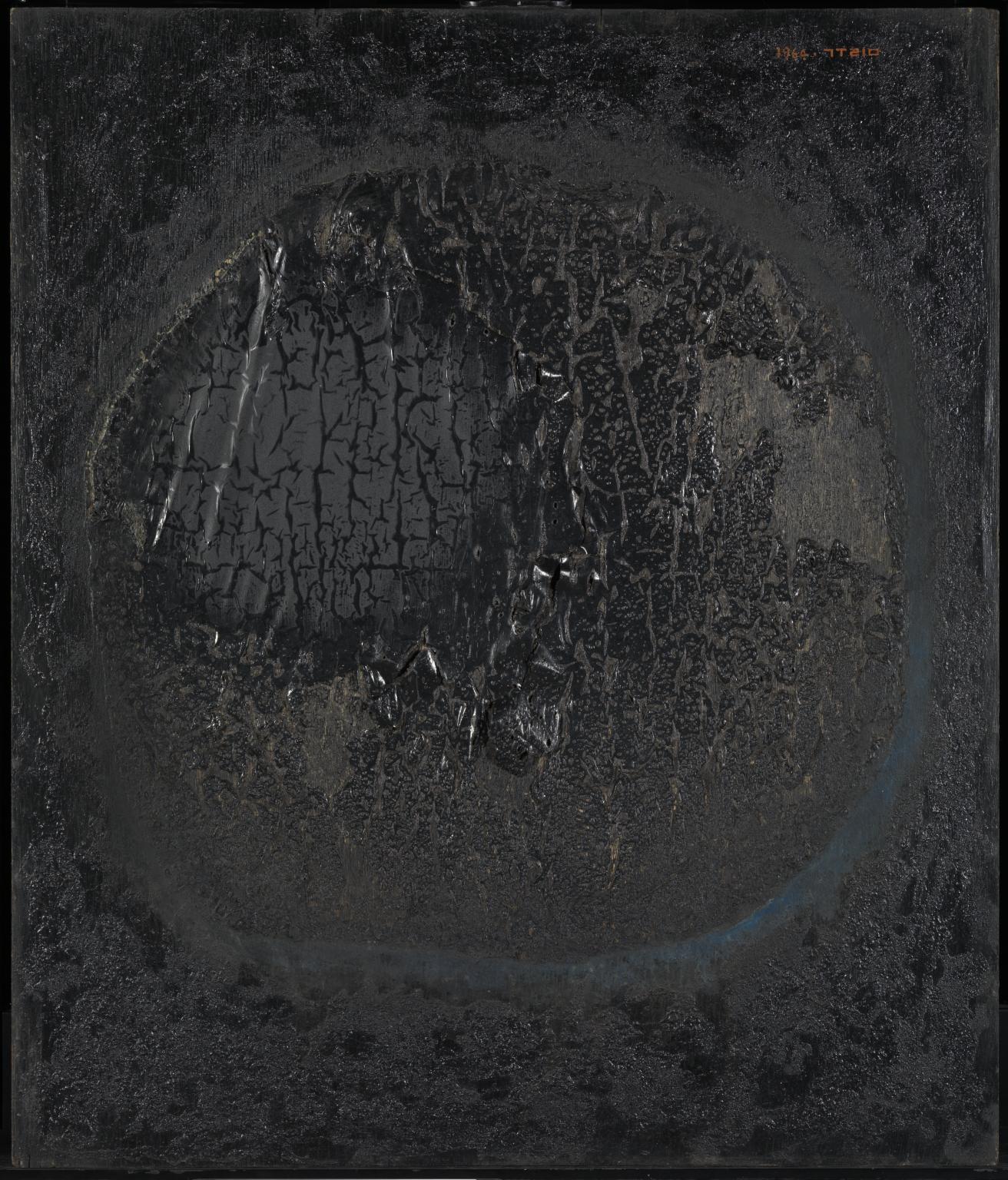

Kim Ku-lim, Death of Sun I 1964

At the centre of this work is a shape reminiscent of the sun, but its surface is filled with charred cracks that the artist made by burning the plastic. It was created in 1964, immediately after Kim completed his military service in Korea: ‘The work is based on my experience of death. I spent some time in the military hospital…where I saw many young men losing their lives. With the lack of medicine and proper medical care, so many lives were being lost, and I felt that human existence was extremely insignificant.’

Gallery label, October 2016

22/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Jeram Patel, Untitled c.1963

Patel began to experiment with burning laminated plywood with a blowtorch in the 1960s. His interest was in the physical properties of the material he used and how it changed through his interventions. He stated: ‘By burning wood, I am making an attack on it… nobody can create anything, the only thing that one can do is to destroy things.’ He rejected colour and representation in works like this, but stressed their relationship to painting. Displaying this on the wall, he felt, helped viewers to see it as an image.

Gallery label, April 2019

23/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Norman Lewis, Cathedral 1950

Cathedral was inspired by the view from Lewis’s studio in Harlem, New York. It is part of a group of works responding to the cityscape he saw from his window. In this series, he combines visual references to the real world with abstraction. The title and the black grid over a red ground might suggest stained-glass windows. After the Second World War, Lewis's work became more abstract. This was partly in response to his disillusionment with the United States. He saw the racist ideology of Nazi Germany echoed in the segregation of races in the US armed forces.

Gallery label, June 2020

24/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Sorry, no image available

Carl-Henning Pedersen, Yellow Landscape 1952

Carl-Henning Pedersen and his wife, the painter Elsa Alfelt (1910–1974), developed a spontaneous style which defied Nazi censorship in wartime Denmark. After liberation they helped to establish CoBrA, an international alliance of artists from Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam. Yellow Landscape relates to Pedersen’s admiration for overlooked artistic traditions, like medieval frescos in Danish churches. He declared: ‘The language of the heart, which is the content of all true art, possesses in itself the swift feet of fire that can reach out to the people and inspire them to create.’

Gallery label, March 2022

25/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

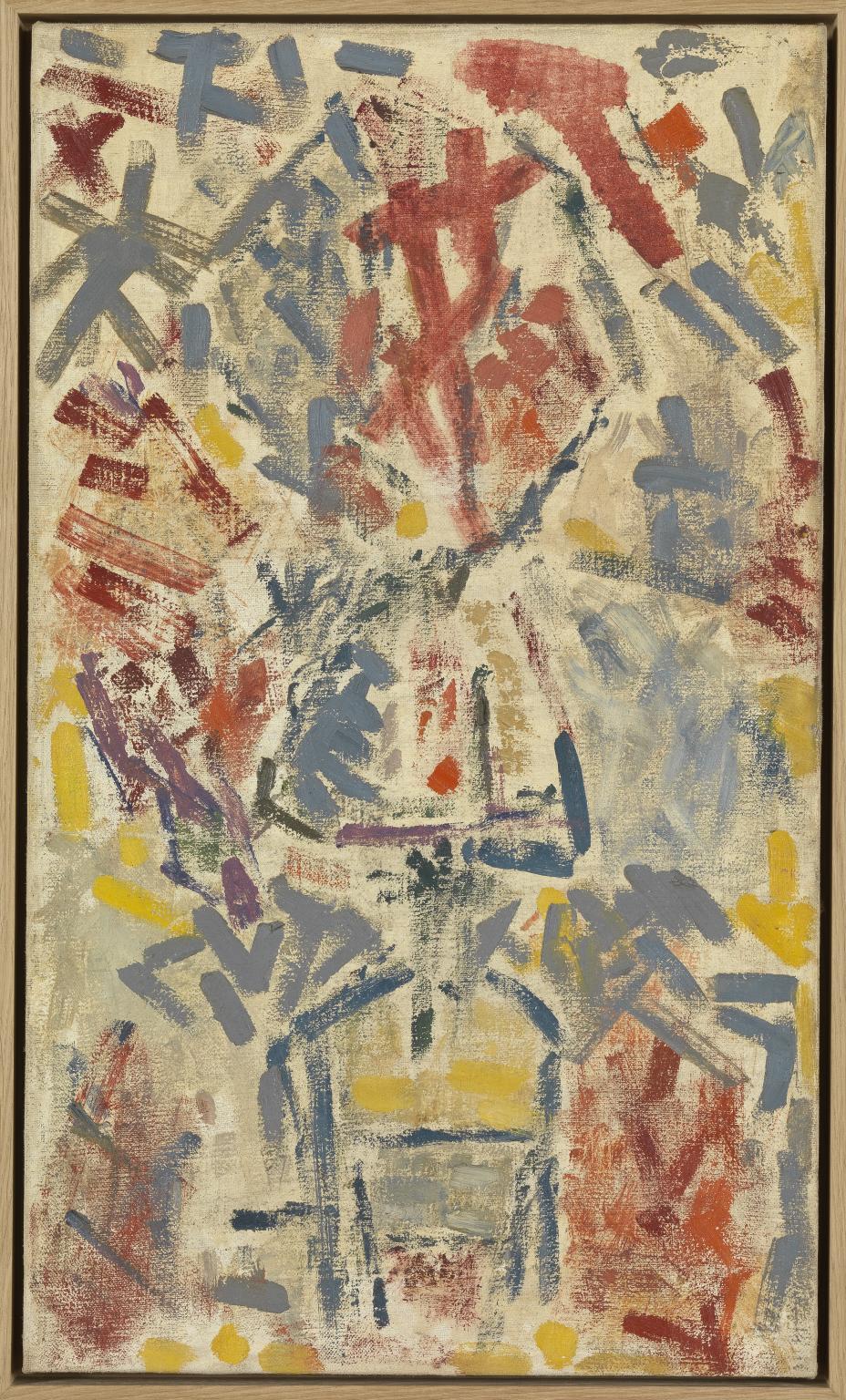

Egill Jacobsen, Composition in Red 1948

Following the end of the Second World War in 1945, artists in Denmark emerged with an energetic style of painting associated with rich colour and spontaneous gesture. Jacobsen was one of the leading figures. Composition in Red was made during a post-war stay in the South of France in 1948. Jacobsen’s work focuses on the image of the mask as an enduring symbol of human expression. He was fascinated that the practice of masking ‘has existed for millennia … in many widely different cultures.’ In Composition in Red the broad oval of a mask sits on top of a central structure that stands for the body whilst being woven into the background by rhythmic forms.

Gallery label, January 2022

26/26

artworks in The Disappearing Figure: Art after Catastrophe

Art in this room

Sorry, no image available

Sorry, no image available

You've viewed 6/26 artworks

You've viewed 26/26 artworks