Since the early 1990s Tate has been working to establish standards of care for the conservation of artworks which incorporate film, video and audio. In this paper I discuss the strategies we are developing and the approach to the conservation of time-based media with reference to a particularly complex installation, Gary Hill’s Between Cinema and a Hard Place 1991. ‘Time-based media’ is a useful term to describe installations which have a duration and therefore have to be experienced in the context of the passing of a period of time.

Fundamental to Tate’s approach to the conservation of contemporary art is the notion that the artist’s intent should guide our practice. Since most of the artists represented by this part of the collection are living, it is possible to interview them about the details of the installation, attitudes to changing technology, parameters of acceptable change and their views about what aspects of the installation are essential to preserve. This is a collaborative exercise that is predicated on the idea that a collector has the responsibility for the conservation of the work.

For much of contemporary art, meaning has shifted away from the unique and precious object and conservation practice has to reflect this and recognise different types of complexity and different types of vulnerability. As Bill Viola has said: ‘As instruments of time, the materials of video, and by extension the moving image, has as part of their nature this fragility of temporal existence. Images are born, they are created, they exist and, in the flick of a switch they die. Paintings in the halls of the museum in the middle of the night are still there, a form of sleep. But in the room of the video projections, there is nothing. The images are thoroughly non-existent gone into some other dimension.’1 Just as a Sol LeWitt wall drawing, when drawn on the wall, does not consist of the set of instructions and coloured pencils, the video installation becomes something other than its component parts when installed. Unlike many objects in Tate’s collection, installations incorporating time-based media are often vulnerable to developments in technology and other factors outside their physical nature. In addition, an installation also contains a fragility inherent in any system. For example, in Gary Hill’s work Between Cinema and a Hard Place, the meaning of the piece is dependent on a multifarious array of technologies that depend on each other and must work together.

An installation such as Between Cinema and a Hard Place is at greater risk than more traditional sculpture of not being installed correctly or not being displayable in the future. Essentially, such works do not really exist until they are installed and each time they are installed they have to depend heavily on those responsible to manage a complex array of detail and to know what it is for the work to be shown correctly. Although a painting can be hung badly, there are fewer things that can go wrong or that can be changed simply as part of the process of putting the work on display. Time-based media installations are often also dependant on technology which quickly becomes obsolete, making it inevitable that elements will have to be changed. How these changes are managed is essential to the conservation of the artwork.

Reflecting the move in contemporary art away from the material object, the conservator’s role has changed to encompass a broader notion of what constitutes the preservation and care of an artwork. Conservation is no longer focused on intervening to repair the art object but has become concerned with documentation and determining what change is acceptable and managing those changes. In order to accurately install works in the future it is necessary to broaden our focus to include elements of an installation that affect the viewer’s experience. This might mean documenting the space, the acoustics, the balance of the different channels of sound, the light levels and the way one enters and leaves the installation. These are as important as the more tangible or material elements in the conservation of the work.

Success is the ability to continue to display these works in accordance with the artist’s intent. A conservator also has a responsibility to preserve the historical quality or character of the work both in relation to the history of contemporary art and the development of an artist’s work throughout their lifetime. Although the conservation strategies employed may look very different from traditional conservation practice, their rationale has its roots in established notions of collections care and management.

Recognising complexity and identifying risk

It is useful when thinking about a complex installation to break it down into smaller parts, listing all the components from the laser disc players to the less tangible details of the space, without losing sight of how the components connect. Against this list, it is possible to assess the role of each element in the realisation of the installation as a whole. One can then consider what are the most likely factors that might prevent each component fulfilling its role. The value of some elements might be functional, the value of others might be aesthetic or sculptural, or perhaps a mixture of the two. Essentially, this is a process of identifying where the dangers or risks lie which might result in not being able to display the work correctly in the future. This should provide a realistic outline for the development of a conservation plan. Conservators do this as a matter of course: if presented with an object made of felt, we are concerned about moths; if presented with steel, we worry about rust. With these installations conservators need to expand their vocabularies of risk to include mechanical breakdown and obsolescence of parts or whole technologies, or perhaps the lack of documentation to guide light levels or the choice or construction of a space in order to install the work.2

Gary Hill’s Between Cinema and a Hard Place

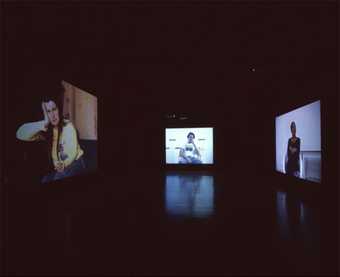

This is a complex installation comprising twenty-three monitors that have been removed from their casing, exposing the circuit boards and cathode-ray tubes and rendering them dangerous and vulnerable sculptural objects. These are arranged in groupings according to size to evoke the clusters of rocks which demarcate farmland.

Via a computer-controlled switching device Hill distributes the images to the monitors according to a defined pattern alongside a spoken text. The images are accompanied by three tracks of audio. On the first track a woman reads an extract from Martin Heidegger’s philosophical essay written in 1953–4, ‘The Nature of Language’. On the second track there is an echo of this voice. On the third track there is a series of abstract sounds, which punctuates the piece three times in an eight-minute cycle.

Hill’s work focuses on the relationship between the viewer, language and image. Among the devices he uses to explore these ideas are the choice of the text, the relationship between the images and the text and the rhythm of the spoken word. The time it takes for the text to be spoken defines the duration of the piece. Against this Hill explores ideas of time which are possible within the medium of video, for example feedback, delay and ideas of ‘real time’. In experiencing the installation, one is aware of the strong rhythm of the words as they are spoken, while the images play in different patterns like an accompaniment set against the notes of a melody. The interplay of sound and images is very precisely controlled and choreographed providing a strong sense of a mathematical structure underpinning the work.

Hill steers us away from the primacy of the image and has said, ‘If I have a position, it’s to question the privileged place that image, and for that matter sight, hold in our consciousness’3 ‘Language can be this incredibly forceful material – there’s something about it where if you can strip away its history, get to the materiality of it, it can rip into you like claws, whereas images sometimes just slide off the edge of your mind, as if you were looking out a car window.’4 It is all too easy as conservators trained to deal with visual media to overlook the importance of the audio. The meaning of the work informs our conservation practice, we need to understand the significance of the sculptural elements of the monitors, the time-based elements of the video and audio, and the nature of the space in order to develop an adequate conservation plan for the work. In many cases the discussions will centre on what changes are acceptable to make. Making and documenting these decisions is an established feature of traditional conservation practice.

Managing the conservation of video

At Tate we have established fairly standard procedures for managing the conservation of the video elements of an installation. When Hill’s work was acquired the conservation department transferred the master material onto a non-compressed component digital tape format at a professional video facility. A conservator is always present for the transfer of master material and in some cases the artist is also present. The conservator’s role is to check the authenticity of the master material as a copy of the original and to check that the colour, brightness and audio levels are correct. In addition, the conservator documents any specific features of the master material for the conservation record and confirms that there are no queries arising during the transfer which should be discussed with the artist before the new archival master is accepted. The archival master tapes all have colour bars and a reference tone for audio at the beginning of the tape and the colour is correct when viewed on a standardly calibrated monitor. At present the most widely supported non-compressed component digital tape format in London is D1. D1 is a professional video format that was introduced in 1986 and complies to the CCIR 601 Digital video standard, as a component video format the luminance and the chrominance information is recorded separately. At present, D1 is the highest quality magnetic recording format in use in the video industry and it allows extensive duplication without loss of quality.

Video tape deteriorates and tape formats change and it is essential that the master tapes are transferred before there is any loss of information. These archival master tapes are checked regularly and transferred onto new stock and new formats when necessary. We expect this to be at least every five years.5 Tate’s master tapes are only played when being checked or transferred or if they are needed to make new discs etc. for display. In addition to making the archival master tapes, we also make a copy on Betacam SP (a professional analogue tape format) and a VHS with time code recorded in picture for reference.

Gary Hill’s installation uses laser disc as its display format. The production and management of high quality archival master tapes makes it possible to make either replacement laser discs, if the originals are damaged, or material on a new display format when laser disc technology becomes obsolete.

At present all video material is stored in a fine art store at 45% RH and 18 degrees centigrade although in the future we hope to develop an area with a cooler environment for the storage of video.

The display equipment

The conservation department also manages the display equipment for works in the collection. On acquisition of Hill’s work, schematics and manuals were also acquired and manufacturers were contacted to discuss parts and spares.

The conservator together with the curator is responsible for ensuring that a work is accurately installed. To achieve this, all the equipment must be fully operational, set up correctly and in good condition. As in the case of the monitors in Between Cinema and a Hard Place, this is not necessarily a straightforward process and it is important that the conservator understands enough about the technology to make the necessary judgements.

The display equipment in Hill’s installation can be placed in two categories. The first contains those pieces of equipment which have become sculptural elements, namely, the cathode ray tube monitors. The second category comprises those elements which are not visible and whose value is functional, for instance, the computer control system and laser disc players. In the following section I will use these examples to illustrate how this distinction affects the conservation strategies employed.

Fig.1

Gary Hill, Between Cinema and a Hard Place 1991

© Gary Hill; photograph Tate

The monitors

The twenty-three cathode-ray tube monitors used in this installation have been modified by the artist and are essential to the look and feel of this work. Of the twenty-three, twelve are 13-inch colour monitors by Panasonic (model CT1383Y); five are 9-inch black and white monitors by Sanyo (Model VM4509) and six are 5-inch monitors by Panasonic (Model WV-5200). These monitors have been taken out of their casing and displayed as exposed tubes and circuit boards. The artist has said that he would not want the cathode ray tube monitors to be replaced by an alternative technology such as liquid crystal display panels or plasma screens, although he would accept the replacement of a deteriorated cathode ray tube with a new tube of the same shape and size.

Fig.2

Gary Hill

Between Cinema and a Hard Place 1991

Detail of a cathode ray tube used in the installation

Cathode ray tubes are common elements of our domestic televisions and desktop computers but are certainly one day set to become rare, given the rapid developments in alternative technologies. This is not a unique problem in the conservation of contemporary art. For example, in the 1970s Dan Flavin made sculptures from standard colours of fluorescent tube which were easily available at the time but some of these colours are now no longer made as manufacturing methods have changed due to the toxic nature of the components.

To exacerbate the problem of obsolescence, the cathode-ray tubes also deteriorate with use. As the tube deteriorates, the brightness and colour balance of the monitor is affected.

The monitors of this installation are set side by side so discrepancies in the colour balance of the tubes are acutely visible. As the tubes get older, colour matching them becomes harder. Colour is produced in television monitors by mixing the colours of red, green and blue. Three scanning electron beams hit the phosphor screen at slightly different angles to excite different phosphors to produce red, green and blue dots. Using potentiometers the strength of the beams can be adjusted, altering the balance of the colour in the picture.

The process of colour balancing takes many hours and much concentration and needs to be carried out while the monitors are powered up. The close proximity to high voltage elements makes this a dangerous procedure. As well as there being a risk of an electric shock, there is also a high risk of the boards shorting out. It may well be that it is not necessary for the conservator to carry out this procedure but rather to understand it and ensure the desired affect is being achieved.

The majority of the monitors were made by Panasonic. Panasonic will usually hold spares for specific components for eight years after production has ceased. Recognising these threats to the long-term life of the cathode ray tubes, we have obtained spares and schematics to facilitate replacement and repair when necessary. On acquisition a full set of spare monitors were acquired. However, even in the few years between the making of the work and the acquisition by Tate, aspects of the design had subtly changed. To date, individual components in three circuit boards have failed and two were successfully repaired by a commercial company recommended by Panasonic.

As the monitors deteriorate while being used, we must also be mindful of the amount of time the work can be on show in the same way as we are with a watercolour or a light-sensitive photograph.

The laser disc players, discs, audio equipment and the computer control system are the functional elements out of view and the conservation strategy here is different. If the technology fails and these elements become obsolete it would be acceptable to the artist to substitute these components with an entirely new technology but only if their function was the same. This is a good way of dealing with the problems of obsolescence and enabling the work to continue to be shown. However, the complexity of precisely mapping the function of a particular technology should not be underestimated. It is appropriate for conservators to be reluctant to change any element of the original technology, and consider it a loss. It might also be argued that precisely reproducing the function is impossible, in the same way that purists argue about the difference between the sound of a CD and a vinyl recording, However, just as it might be necessary to replace old varnish in order to be able to still see a painting, it is important to prepare for the replacement of these elements of equipment in order to continue to be able to show the work. As with any intervention, the conservator must justify such a change in accordance with the code of conservation ethics which governs the profession.

Each part of the display equipment is dependent on each other in order to create the resulting play of images and sound. If one element is changed, for example, the use of laser disc technology, there is a risk that the whole system could collapse and no longer work correctly. It is therefore necessary to understand the precise role of each piece of equipment – what they do and how they relate to each other and how the system functions as a whole.

The Computer control system

The system that controls which images are sent to which monitors at what time, is made up of the laser disc players and discs, the laptop computer, the time code reader, the synchroniser and the video switcher.

The value of the laser disc players is largely functional and the risk factors to consider, in this case, are mechanical failure in the short term and the obsolescence of the whole technology, in the medium term. The actual object, the laser disc player, is not visible and its appearance is not significant to the artist’s choice of the model or the technology. Rather, it is the ability of the laser disc players to provide a frame accurate reference in their delivery of sound and images which is the basis of their value to the installation.

The display format of the audio and video is the CAV (constant angular velocity) laser disc. These discs rotate at a constant speed and one revolution of the disc corresponds exactly to 1 frame. This makes it possible to accurately reference one frame on the disc. Each disc has three sections of video recorded, each of which is exactly, to one frame, 8 minutes and 15 seconds long. Each section has two audio channels. The audio channels for the section played by ‘Player one’ provides the analogue time code signal. This is sent via a standard phono plug to a time code reader, and the spoken text in English. The audio channels for the section played by ‘Player two’, provides the echo of the spoken text in English and the spoken text in German. The audio channels for the section played by ‘Player three’ provides the echo of the German text and the abstract sounds that punctuate the piece. When installed, it is possible for the text to be spoken in either German or English.

A synchroniser built and designed by Dave Jones Design tells each of the discs to start playing a portion of the disc at a particular frame, providing accurate synchronised playback.

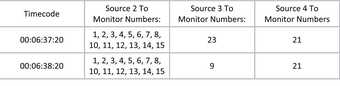

The second audio output plays an analogue time code signal and is connected to the time code reader. The time code reader converts this analogue signal to a digital data stream that goes to the computer. When the computer receives the time code information, it looks it up in the data file: if there is a match, it sends the information to the video switcher. The video switcher will treat these as instructions and send the video to the monitors as instructed. The work is created with three possible streams of video image plus black and the switcher can show those images in any combination on any of the monitors.

The computer control system is not a mass-market product but was developed by Dave Jones Design. Using this system, Gary Hill wrote the specific program that runs Between Cinema and a Hard Place. With the help of Dave Jones it has been possible to access the program and to write a description of the data file. The result is akin to a score describing the 3199 different actions written in the program. The actions or changes determine which section of the laser discs are played at what time, on which monitors and for how long. Below is a sample of one row from the documentation for the control program. The fragment shown below tells us what is happening at a particular moment 6 minutes, 37 seconds and 20 frames into playing the discs.

With the complete document it would be possible, if it became necessary, to use this as a basis for writing a program using a different system – maybe for a different display technology and map the function. Mapping the function of the elements in this way helps to lessen the dependency of the installation on any particular technology or item of equipment. The software designed by Dave Jones, the program written by Gary Hill for this work and a copy of the DOS operating system are stored on Tate’s main server and also on CD.

Hill says of this work:

Between Cinema and a Hard Place plays with the construct of frames as it relates to photography and cinema. Images from single sources are distributed by computer – controlled electronic switching to several monitors. There are certain sections where scenes divide into two scenes, three scenes and so on. With each division all the scenes slow down – half speed, third speed, quarter speed etc. It is a kind of telescopic time that makes the viewer aware of the process of seeing – of beholding the world through sight that exists in the folds of time.6

With the information from the program it is possible to precisely pinpoint a section which Hill gives as an example to the ideas referred to in this passage using a time code reference. There is a section where images that have been recorded in real time are played back on four monitors. Each monitor displays a particular sequence, a trowel digging the soil, the removal of clothes hanging on the back of a chair etc. When the scene is not being played on any one monitor, there are two frames of black. This has the effect of making the images appear to be slowed down. In the same way as we might be interested in the way a painter employs brush stroke to create the intensity and energy of the image, here we can see how the artist has manipulated the medium of video to create a study of the world, time and language.

Conclusion

In developing strategies for the care and management for works such as Gary Hill’s installation Between Cinema and a Hard Place, the conservator has a number of options and tools. It is possible to manage electronic material in order to avoid loss by transfer onto new stock and new formats as necessary - this is a matter of good housekeeping. By understanding the mechanics of these installations and the technology involved conservators are able to precisely map the function of elements before they fail so they can be accurately transferred onto different technologies as obsolescence looms. It is also necessary to work with industry and specialists outside the field of conservation to develop new skills to preserve and manage new types of objects in our care. We can also document the less tangible details of an installation such as the light levels, the character of the sound etc. This is a new area of conservation and as a profession our understanding and knowledge will deepen with time. All of these strategies work together to help to limit the risk of not being able to accurately install these works in the future. Deciding what can be changed and how to best care for any element of an installation will depend on its meaning and role. For both contemporary and traditional objects such decisions are documented by conservators and although the focus of the conservator may have moved away from the material object, the approach is still rooted in traditional notions of collection care.