In Tate Modern

In the Studio

Free- Artist

- André Derain 1880–1954

- Original title

- Le Peintre et sa famille

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 1765 × 1238 mm

frame: 1897 × 1360 × 114 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1987

- Reference

- T04923

Display caption

This symbolic painting represents the life of an artist. It is an invented scene. Despite usually working alone in his studio, here Derain paints himself surrounded by his family. Through the deployment of figures, animals, and objects Derain expresses his personal philosophy as an artist. His wife reads a book of myths, signalling their shared literary interests. His niece holds a dog, a medieval symbol of loyalty. His sister-in-law serves refreshments, her pose recalling earlier European paintings which had influenced Derain. The animals and fruit are also symbolic, alluding to various esoteric and artistic themes.

Gallery label, July 2021

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

T04923 The Painter and his Family c. 1939 Le Peintre et sa famille

Oil on canvas 1765 × 1238 (70 × 48 3/4)

Inscribed ‘a. derain’ b.r.

Purchased from Galerie Schmit, Paris (Grant-in-Aid) 1987

Prov: Inherited by Alice Derain, the artist's wife, 1954; inherited by André Derain, the artist's son, 1975; purchased by Galerie Schmit late 1986

Exh: André Derain: Paintings from 1938 and After, Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, April–May 1940 (2, as ‘La Famille’); Paintings by André Derain, Arts Club of Chicago, Jan. 1947 (19, as ‘Derain Family’); Derain, Musée nationale d'art moderne, Paris, Dec. 1954–Jan. 1955 (91); Derain, Arts Council, Royal Academy, Sept.–Nov. 1967 (86, repr. p.80); Derain connu/inconnu, Museé Toulouse Lautrec, Albi, June–Sept. 1974 (31); Exposition Derain 1880–1954, Galerie Schmit, Paris, May–June 1976 (58, repr. p.117 in col.); Hommage à André Derain, Musée d'art moderne de la ville de Paris, Dec. 1980–March 1981 (no number, repr. p.38); André Derain, Takashimaya Art Gallery, Tokyo, April–May 1981, Takashimaya Art Gallery, Osaka, May 1981, Takashimaya Art Gallery, Kyoto, May–June 1981, Nagoya City Museum, June–July 1981 (57, repr. p.89 in col.); A. Derain, Musée de Melun, France, May–July 1984 (18); Maîtres français: XIX et XX siècles, Galerie Schmit, Paris, May–July 1986 (25, repr. in col.); Bilderstreit: Widerspruch, Einheit und Fragment in der Kunst seit 1960, Museum Ludwig, Cologne, April–June 1989 (147, repr. p.459 in col.); André Derain, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, Dec. 1990–March 1991, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, March–May 1991, Musée d'art de la ville de Troyes, June–Sept. 1991 (55, repr. p.138 in col.); André Derain: Le peintre du ‘trouble moderne’, exh. cat., Musée d'art moderne de la ville de Paris, Nov. 1994–March 1995 (167, repr. p.249 in col.)

Lit: Doris Brian, ‘The New Derain’, Art News, vol.38, 20 April 1940, pp.10, 21, repr. p.10 as ‘La Famille’; Malcolm Vaughan, Derain, New York 1941, p.76, repr. p.43 (col.) as ‘Derain Family’, dated 1940; Denys Sutton, André Derain, 1959, p.45, repr.fig.75 (col.); Denys Sutton, ‘André Derain’ in André Derain 1880–1954, exh. cat., Wildenstein Gallery 1957, p.xvii; Pierre Cailler ‘André Derain 1880–1954’, Documents, Geneva, no.13, 1959, p.10, dated 1938; Denys Sutton, “'Self-Portrait with a Cap” by André Derain’, Apollo, vol.116, July 1982, pp.44–5, repr.; Tate Gallery Report 1986–8, 1988, p.70, repr. (col.); Jane Lee, ‘Derain's “The Painter and his Family”’, Burlington Magazine, vol.130, April 1988, pp.287–90, repr. p.288 (col.); Simon Wilson, Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion, 2nd ed., 1990, p.169, repr. (col.); Jane Lee, Derain, exh. cat., Museum of Modern Art, Oxford 1990, pp.133–4, repr. fig.88 (col.). Also repr. Georges Hilaire, Derain, Geneva 1959, p.176; Gaston Diehl, Derain, Paris 1991, p.83 (col.); André Derain: Le peintre du ‘trouble moderne’, exh. cat., Musée d'art moderne de la ville de Paris, 1994, p.248, repr. p.249 in col.

This painting shows the artist at work at his easel, surrounded by members of his family and pet animals. In the foreground his wife Alice is reading a book. Immediately behind him, his niece Geneviève holds a dog, while Suzanne Géry, Geneviève's mother and sister of Alice, enters the room, holding a tray. The controlled nature of the composition, as well as the surprising presence of the parrot, cat and peacock, suggest that the painting should not be seen as literal description of the artist's studio, but, rather, as an allegorical statement of Derain's view of his work as an artist. Allegory, and, more generally, the construction of meaning through emulation of the subject matter and styles of particular types of past art, had long been central to Derain's vision of art, and the complex iconographic and stylistic references found in T04923 should be seen in the context of a small number of earlier works by the artist.

Derain had painted a number of portraits of himself as an artist (in addition to simple self-portraits) from his earliest years. A boldly-painted canvas of 1903 shows him standing with his face towards the viewer and holding a brush and palette, as if caught in the act of painting (repr. Galerie Schmit exh. cat., 1976, no.3, as ‘Autoportrait dans l'Atelier’). Responding to the simplified, angular style of Italian and French ‘primitive’ art of the fifteenth-century, Derain portrayed himself in 1912 with highly stylised, elongated features, and a paintbrush - the emblem of his profession - in his hand, beneath the rubric ‘ANDRE DERAIN PEINTRE’ (repr. Paris exh. cat., 1980, p.36, as ‘André Derain, peintre’). A similar ‘Gothic’ style can be seen in the slightly later ‘Portrait of the Artist’, c. 1913–14 (Minneapolis Institute of Art, repr. Lee 1990, p.125, fig.81), in the monochrome ‘Self-Portrait’, 1913 (repr. Paris exh. cat., 1994, no.110 in col.), and in a second work of the same title and date (repr. ibid., no.109 in col.).

Nearer to T04923 in both composition and style is ‘The Artist in his Studio’, 1920–1 (repr. Lee 1990, p.127 in col.). In this highly staged self-portrait, the artist is shown at the centre of the picture, holding a palette in his left hand, next to an unworked canvas on an easel. At the lower left, a small boy holds a bowl of fruit, and looks out towards the viewer. On the table are a pipe, spoon, and some fruit, all lying on a white cloth, as well as a vase of flowers. To the right of, and immediately behind, the artist is a figure who was most probably the artist's wife, Alice. She wears a white drape, and is posed as a model.

Almost twenty years later, Derain included many of the same elements in T04923. Here he represents himself at work in the company of his wife (again with her back to him), and a servant figure (his sister-in-law carries a tray), and facing an arrangement of fruit and flowers. Both works have similar dark colours (predominantly black, enlivened with green, red and white), and a compressed pictorial space; in each a dark curtain partially blocks the view of the back of the studio. Derain is known to have executed two other self-portraits as an artist in the interwar period (‘Portrait of the Artist’, before 1928, repr. Lee 1990, p.125, fig.82, and ‘The Artist’, 1930, repr. André Derain 1880–1954, exh. cat., Grace Borgenicht Gallery, New York 1987, [p.3]), but these are minor works, and ‘The Artist in his Studio’, 1920–1, should be seen as the direct forerunner of T04923.

Like T04923, the self-portrait of 1920–1 shows a marked debt to past art. The simplified features of the servant boy, as well as the compressed pictorial space, recall Derain's pre-war ‘Gothic’ phase, inspired by Byzantine and medieval art. However, the painting's pyramidal composition and rich tonality suggest a debt to High Renaissance art. With its ‘correct’ perspective, illusionistic handling, and standardised subject themes, Renaissance art had been anathema to an earlier generation of radical artists (including Derain in his Fauve period). However, in the late 1910s and 1920s, Derain, together with such artists as Picasso and de Chirico, pioneeded a re-evaluation of the art of the museums in the movement that became known in France as ‘le rappel à l'ordre’ (‘call to order’). In 1920 Derain was particularly interested in the paintings of Raphael (De Chirico shared this interest, and executed a faithful copy of a Raphael portrait in 1920, ‘La Muta, after Raphael’, private collection, repr. On Classic Ground, exh. cat., Tate Gallery 1990, p.75 in col.). In his contribution to the critical debate surrounding the quatercentenary exhibitions of works by the Renaissance master, Derain described Raphael as a great, but still generally misunderstood, artist (Le Matin, 6 April 1920, p.l, quoted in Lee 1990, p.61). An echo of the famous Raphael portrait, ‘Baldassare Castiglione’, before 1516, (Musée du Louvre, Paris), can be found, perhaps, in ‘The Artist in his Studio’, particularly in the artist's pose, and the contrast of the white cravat with the subtle greys and blacks of his jacket. The painting certainly employed a symbolism that was characteristic of Renaissance art. The artist's right hand points to himself, underscoring the painting's allegorical purpose; the model fulfils the traditional role of artist's muse; while the boy offering the artist a bowl of fruit can be seen as implying it was the role of the artist to describe nature and its beauty.

Derain's views on art and on the function of the artist can be pieced together from the aphoristic notes he wrote in the early 1920s in preparation for a treatise on painting, ‘De Picturae Rerum’, that he never finished (see previous entry). Near the beginning of the text he referred to Greek, African, Scythian, and archaic art, and suggested that in all types of art there were certain recurring features that belied temporal and cultural distinctions (‘Constants in lost civilisations. Continuity made of exterior forms perpetually discovered’, in ‘Notes d'André Derain’, Cahiers du musée national d'art moderne, vol.5, Paris 1980, p.348). Derain studied esoteric subjects such as alchemy and the cabbala, as well as mysticism and Eastern philosophy; and his writings show a gnostic or religious approach to the question of the relationship of spirit and matter. He believed that there was a divine ‘signature’ in all things, and that it was the artist's role to sense this presence and embody it in his work. However, this divine force was never to be revealed: ‘Blessed are those who veil nature (that is to say, objectivity)’, he wrote, ‘to make others believe in the divine. The divine ought to be veiled and matter ought to be the apparent goal’ (ibid., p.351). In other words, the artist's work was almost as mysterious as the alchemist's dream of transmuting base metal into gold, or the transubstantiation of wine and bread in the Eucharist. Art, Derain argued, should be based on an intuitive rather than rational understanding of the world (‘Ideas are not enough. A miracle is necessary. Popular art gives proof of paroxysm’, ibid., p.357).

Derain's vision of the artist as a kind of sage or priest may help explain why he chose to represent himself at the centre of ‘The Artist in his Studio’, and again, nearly twenty years later, in T04923. His few published statements of the 1930s and 1940s show that Derain increasingly stressed this notion of the artist as a repository of tradition, both artistic and spiritual. In an important text published in 1943 (see previous entry) Derain declared, ‘The mission of art is to equalise time’, by which he meant that art should be concerned with the universal truths that lay at the base of all human experience. Art, he said, was always the same beneath its apparent forms. ‘Why should there be change, since in fact the spirit remains the same, and we retain the same moral attitudes. Isn't the place of man before the universe and before himself, always the same? ... Art is, and will always be, the memory of generations’ (Collection Comoedia-Charpentier, Peintres d'Aujourd'hui: Les Maîtres, Paris 1943, pp.9–10).

Derain clearly hoped that by emulating the particular types of past art he admired, he was in some way making contact with, and in turn expressing, fundamental or universal facts about human experience. Although Derain's taste in art was catholic, as his collection of art works from many parts of the world and of different epochs showed, his paintings were mainly inspired by art from the period of the Renaissance to the eighteenth century. The typology and symbolism of the art of this pre-revolutionary epoch clearly suited Derain's vision of art, as well as his conservative temperament; and his unmistakeable allusions in many of his works to a specifically French tradition of painting won him the approval of such conservative critics as André Salmon and Waldemar Georges, as well as considerable commercial success.

The theme of an artist's self-portrait was associated particularly with art of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Perhaps the most famous work was Velasquez's ‘Las Meninas’, 1656 (Prado Museum, Madrid), showing the artist at work amidst members of the Spanish royal family and its servants. It is possible to argue that there are compositional similarities between the Velasquez and T04925: in both the artist is shown behind the ostensible subject of his painting, while one or more figures can be seen at a doorway behind him. Among examples of portraits of the artist at work in the collection of the Louvre, Derain would almost certainly have known ‘Charles Le Brun, Painter to the King’, 1686, by Nicolas de Largillière, ‘Jean-Baptiste Oudry, Painter’, 1753, by Perronneau, ‘Hubert Robert, Painter’, 1788, by Elizabeth Vigée-Le Brun, as well as the more modern ‘Portrait of the Artist’, 1825, by Corot, whose work Derain particularly admired.

There was, however, an even more modern work on this theme which Derain would also have known: the great allegorical painting, ‘The Artist's Studio’ by Gustave Courbet (1819–77), acquired by the Louvre in 1920. In this Courbet represented himself at work, surrounded by a crowd of writers, artists, as well as ordinary people, symbolising the combination of artistic interests and real life that he saw as central to the work of an artist. Derain admired the earthy quality of the works of Courbet, who was increasingly recognised in the 1910s and 1920s as one of the great masters of French painting (see Lee 1990, pp.57–60); and it seems likely that, in his conception of T04925, as well as of the earlier ‘The Artist in his Studio’, Derain was partly inspired by the latter's masterpiece.

Unlike Courbet, however, Derain insisted on the private or domestic nature of art, staging both self-portraits as an artist in an familial setting. In this Derain is closer to the relatively informal, albeit tightly composed, scenes of painters at work found in seventeenth-century art. Jane Lee (1990, p.133) cites the series of artist portraits by Nicolas de Largillière, several of which were exhibited at the Petit Palais, Paris in 1928, as a possible source for the composition of T04923, as well as for what she sees as its special emphasis on the artist's face. She writes:

In Derain's painting, the sweeping extended curves and the build-up of shallow space from a close overlapping of planes reveal the influence of the seventeenth-century master. Although Largillière's portraits were often elaborately composed and rich in allusive detail, they included an intense characterisation of the artist's face. The face of Derain might be compared with that of the painter ‘Jean-Baptiste Forest’ in Largillière's much copied masterpiece in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lille ... The major compositional structure of Derain's painting - opposing diagonals, one along the easel, the other through the artist and his niece - is a mannerism of the years around 1700.

Lee also gives as a possible source for this use of diagonals a painting in the Louvre by another artist of the same period, ‘Portrait of the Artist in Hunting Dress’, 1699, by François Desportes. In this the artist is shown off-centre, leaning to the right, while holding a rifle which points outwards to the left (repr. ibid.). This seventeenth-century painting was an important inspiration for Derain's ‘The Deer Hunt’, c.1935, (Musée d'art moderne de la ville de Troyes, repr. Lee 1990, p.83 in col.), and it is possible that it also influenced the composition of T04923. Lee (1988, p.28) notes that Derain's ‘The Deer Hunt’ and T04923 are both painted rather flatly, and she relates this to Derain's contemporary designs for tapestries. ‘Characteristic also of the “tapestry period”’, she writes, ‘is the isolation of each element, giving each part of the painting an emblematic power. The strong silhouettes which achieve this isolation create arabesques which flow across the organising compositional grid. Clarity of design and daring simplicity of drawing hold together a disparate composition with baroque grandeur’.

For Jacqueline Munck (Paris exh. cat., 1994, p.248), however, the obviousness, and theatricality, of these allusions to past art suggest an ironical meaning. In her view Derain expressed his ‘disillusionment ... with the academic forms of the allegorical portrait’ and ‘a certain derision’ in representing his household in the manner of an eighteenth-century interior. Derain based his self-portrait in T04923 not, as might be expected, on a mirror reflection, but on a photograph of the artist's head and shoulders taken in 1935 by Rogi André, a young woman amateur photographer (a copy of this photograph, the original of which belongs to Robert Stoppenbach, London, is in the collection of Tate Gallery Archive). André held an exhibition of about forty portraits of writers and artists including Derain in 1935, but little else is known about her. A distinguished and charismatic figure, Derain was much photographed in the interwar years, and was himself an amateur photographer. He regularly used photographs of figures as sources or guides for works, whenever models were not available. As early as 1905, for example, he used a photograph of a studio mock-up of a scene as a basis for an early painting of 1903, ‘Soldiers' Dance at Suresnes’ (repr. Lee 1990, fig.6 in col.).

Derain's use of a photograph as a basis for his self-portrait in T04923 underscores the artificiality of the scene, which certainly did not represent his normal working conditions. From 1935 Derain lived at La Roseraie, a large country house with several outbuildings, at Chambourcy, near St Germain-en-Laye. Although he continued occasionally to work in a studio at rue d'Assas in Paris, his main studio was in a large, well-lit room at the top of the house at Chambourcy. However, according to Geneviève Taillade in conversation with the compiler on 5 August 1992, Derain tended to work in a downstairs sitting room in the mid and late 1930s. Importantly, neither this room nor his top floor studio resembled that shown in T04923. Although the table and the bench on which Alice Derain sits were probably based on real furniture in La Roseraie, the draped green curtain and the window, high in the right hand corner of the painting, were invented. They were, however, standard elements in Renaissance compositions, and were no doubt intended to be interpreted as such.

The white tablecloth, and the smaller, crumpled cloth (presumably a napkin) lying casually on top of it, were commonly recurring elements in Derain's paintings. Such cloths provided a usefully neutral background for colourful elements such as fruit and flowers, but it is also possible that, as areas of whiteness, they also bore certain spiritual connotations in some of Derain's works. In ‘Saturday’, 1912, (repr. Lee 1990, p.44, as ‘Le Samedi’, Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow), for example, three women are shown engaged in apparently domestic activities. However, as Jane Lee has convincingly argued, they are also performing part of the catholic ritual of Easter Saturday: one holds a bowl; another seems to bless the bowl, whilst also holding a book, representing the Bible; and the third is sewing a white cloth, which, against the background of an open tomb, glimpsed through the window, seems to allude to the sepulchral cloth of Christ. Although T04923 is not a religious work, it seems likely Derain intended the table cloth to suggest an area of a certain spiritual, as well as visual, purity, separating the viewer from the artist: in this way, the artist is represented almost as a priest behind an altar.

When Derain came to paint T04923, marked contrasts of light and dark were very much an established feature of his general painting style (see also previous entry on T04863). In his concern to emphasise the play of light Derain added small, scarcely perceptible markings in what appears to be white chalk to the bench and peacock, at least six months to a year after the oil paint had dried. It is not clear whether or not these highlights were added before the painting was sent to America in February 1940 or after it returned c. 1950. He had also used this most unusual technique in T03368, ‘Madame Derain in a Shawl’, c. 1919–20. The marked contrast in the illumination of the artist's face, and that of his ‘muse’ behind him, with the prevailing darkness of the surrounding space, suggests that Derain may have been using light as a metaphor for spiritual illumination in the act of creation. If so, the tray with its decanter and two cups, which is located in the space between the artist and his easel, may have an almost eucharistic symbolism; its presence at the centre of the composition, surrounded by darkness, may be intended to suggest a mystical aspect to the transformation of paint and canvas into an imagined reality in the creative act.

In the lower left corner of the scene sits the artist's wife, seemingly absorbed in the book she is reading, with her face largely in shadow. Derain first met Alice in 1907 when she painted a little and knew many of the artists and writers of Montmartre. Their whirlwind romance ended her marriage to Maurice Princet, a mathematician who was particularly interested in the theories regarding memory and time of the philosopher Henri Bergson: Alice was a striking woman, both serene and elegant. Gertrude Stein described her as ‘rather a madonna like creature, with large lovely eyes and charming hair’. She added that she also ‘had a certain wild quality that ... was curiously in accord with her madonna face’ (The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, 1966, p.29). She was a close friend of the great fashion designer of the period, Paul Poiret, and mixed easily with artists and writers. (Clive Bell remembered the Derains holding a kind of court amongst the painters and poets in the café ‘Les deux Magots’: ‘Derain was the presiding genius and Alice Derain the lovely and gracious queen’ (Old Friends, 1956, p.175, with photograph showing the Derains in the 1920s following p.176). A practical and capable woman, Alice Derain also acted from time to time as an intermediary between her husband and dealers and collectors.

Derain painted her on a number of occasions. An early Fauve portrait dates from the beginning of their relationship (‘Mme Derain in Green’, 1907, Museum of Modern Art, New York, repr. Regina 1982, no.12), while her fashionable elegance is brought out in two portraits of 1922 (both ex coll. André Derain fils, repr. Lee 1990, nos.48 and 49). However, the portrait that is closest in mood to the representation of Alice in T04923 is a work also in the Tate Gallery's collection, ‘Madame Derain in a White Shawl’, c.1919–20 (T03368). Here Alice is shown seated on a chair, her face impassive and rendered in a manner that recalls both Pompeian wallpainting and archaic terracotta figurines (Derain explored a wide range of sources in seeking to create ‘classical’ or, as he thought of it, ‘timeless’ art). As in T04923, she is shown with a cat (drawn in chalk and preserved with fixative) and flowers, while there is even the suggestion of the corner of a book on the table. Behind her, too, are a curving green curtain and a window, through which can be seen clouds in a blue sky. In its depiction of Alice, as in other aspects, T04923 is remarkably similar to a work of twenty years earlier.

Alice's pose of sitting quietly reading evokes an atmosphere of domestic harmony and intellectual endeavour. However, Derain had used the image of a woman holding a book in ‘Saturday’, 1912–13, to refer to the Virgin Mary, and it seems likely that here, too, he was making a direct appeal to the two allied themes found in Renaissance painting, the Virgin reading and the Virgin seated before St Luke who paints her portrait. Lee (1990, p.134) points out that these themes had been combined in Dutch seventeenth-century painting, and suggests that Derain had been inspired by Michiel van Musscher's ‘Portrait of the Painter Michiel Comans II and his Wife’, 1669 (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). Lee adds that, ‘the complex play of light in Derain's picture is also a indication of the importance of seventeenth-century Dutch painting in Derain's work in this period’ (ibid.).

The other women in this portrait of the artist's family were Alice's sister, Suzanne Géry and her daughter Geneviève. Suzanne and her daughter, who was born in 1919, lived for a while at her family home, but when her father died in 1924 they moved into a country house owned by Derain. From 1928 they lived with the Derains in their house at rue de Douanier, Paris, until 1935, when they all moved to La Roseraie at Chambourcy. There Suzanne and Geneviève lived across the courtyard from Alice and André, and remained an intimate part of Derain's family circle.

Derain took a close interest in Geneviève's development, and treated her as his own daughter. He painted her many times, and, especially following the family's move to Chambourcy, she became a favourite model. In ‘The Boa’, c.1935 (repr. Vaughan 1941, p.39 in col.), for example, Derain painted her in a nineteenth-century style dress, with a feather boa. A few years later, in ‘Geneviève with Mantilla’, c.1937 (private collection, France, repr. Lee 1990, p.132), he depicted her in the manner of a Renaissance Madonna. Interestingly, the position of her hands in this painting, one above the other, anticipated Geneviève's pose in T04923.

Renaissance portraiture seems to have provided the inspiration for ‘Geneviève Holding an Apple’, 1937–8 (private collection, France, repr. Lee 1990, p.139 in col.), in which she is shown leaning on a table, her face emotionless and her eyes averted from the viewer. A strong light illuminates half her face, and plays on the contours of her arms, distinguishing them from the black background. As in T04923, she wears a red-brown knitted jumper, only short-sleeved and buttoned at the neck (in conversation with the compiler Geneviève Taillade confirmed that this jumper, which she knitted herself c.1937–8, had short sleeves, not long ones as depicted in T04923). Her hairstyle is the same, and in both works only a certain pensive or anxious look about the eyes gives life to her face. In this earlier portrait there is also a white tablecloth, crumpled napkin, and what appears to be the same black fruit dish, together with individual pieces of fruit, including a solitary pear to the left of the compotier. The composition shows a clear debt to Renaissance painting, and, in particular to Raphael, whose works had first influenced Derain in the early 1920s. As Lee (1990, p.133) writes, ‘The direct influence of Raphael on Derain's portraits of his niece at this time is striking, and [‘Geneviève Holding an Apple’] owes a great deal to Raphael's self-portrait now in the Uffizi’. She also notes that Derain possessed a book of reproductions of Piero della Francesca's ‘Dream of Constantine’ (S. Francesco, Arezzo), which might have been a source for the particularly dramatic lighting in this portrait of Geneviève.

In T04923 a warm light suffuses Geneviève's face, creating hardly any shadows. Although the artist is undoubtedly the focus of the composition, the luminosity of Geneviève's face, above and behind his, draw the viewer's eye upwards. Lee (1990, p.134) argues that Genieviève's position behind Derain suggests that she is being represented as his guiding spirit or muse, and cites in comparison ‘The Composer Cherubini with the Muse of Lyric Poetry’, 1842, by Ingres (Musée du Louvre). This association is strengthened by the fact that Geneviève is shown holding a dog. Geneviève Taillade recalled that the dog was called Finette and was a stray found by the Derains at the time of the Munich crisis in September 1938. In the context of the allegorical role of the different elements of T04923, the dog, which in medieval and Renaissance art was a symbol of fidelity, should perhaps be seen as a sign of Geneviève's loyalty to the artist: as she represents, or stands in the place traditionally allotted to, the artist's muse, the dog might also be seen as a symbol of the artist's devotion to his art.

Alice, Suzanne and Geneviève made up what Derain once described as the ‘feminine side’ of his life (letter to Pierre Levy, 11 Jan. 1950, quoted by Lee 1990, p.133); and it was surely significant that in a work which expressed his vision of art, Derain chose to represent himself in the midst of this domestic circle, cut-off from the outside world. Although it is not known why Derain chose this theme, it is possible to speculate that the worsening political situation and approach of war led him focus on his family and its importance to him.

Jane Lee has argued that Derain may have been drawn to stress his belief in the private and individual nature of art in the face of the growing interest amongst younger artists in politically committed realist art. A few years earlier, Derain was seen by many as champion of the cause of the new realism. In particular, his statement in the Communist journal Commune in 1935 that art ‘should be understood by all’, and that the artist should be ‘educated by the people’, had been seen by some left-wing artists and writers as encouragement for their attempts to define a new realism in art, to be based on the tradition of Goya and Manet. However, Jane Lee (1990, p.80) writes, Derain was soon to disappoint the active Communists, ‘with his bourgeois sense of the place of art and artists in the political world, refusing in 1936 to attend the conference “La querelle du réalisme” on the basis that lectures were not only boring but damaging to an artist’. Derain did not believe that art was nourished by, or should be subject to, theories or doctrines, and insisted that it was rather a matter of individual expression. ‘I am not attached to any principle - except that of liberty’, he was reported as saying in 1945, ‘but my idea of liberty is that it must be related to tradition. I do not wish to expound any theories as to what ought to be done in the arts. I simply paint the best that I can. The point is that there are too many theories running around and not sufficient passion to make them work’ (interview with Gotthard Jedlicka, quoted in Sutton 1959, p.48). The enclosed, meditative atmosphere of the studio in T04923, and the presence of figures who, in different ways, expressed qualities of calmness, fidelity and application, were Derain's chosen metaphors for what he saw as the necessary seclusion and single-minded concentration of the artist.

However, Derain did not believe the artist should be cut off from the natural world: the studio in T04923 teems with life, and it is possible that Derain was implying in this that the artist should always retain contact with nature. Interestingly, animals are found in two recently published drawings of subjects related to T04923. In one, Derain has sketched a curiously young and feminine artist holding a palette, with a cat on his/her shoulder, a dog at the foot of an easel, and a bird in the background (repr. André Derain: Dessins inconnus 1901–1954, Paris 1992, p.40, as ‘Le Peintre dans son atelier’). In the other, there are two dogs in the artist's studio, which, significantly, shows a window behind the artist, a curtain to one side, and a small female figure about to enter from the left (repr.ibid., p.41, as ‘Intérieur du peintre’). Unfortunately, these works are undated, and it is not clear to what period in Derain's work they belong.

Each of the animals in T04923 can be seen as having a symbolic meaning. Geneviève Taillade has confirmed that there was no parrot at Chambourcy, although its presence in the painting may have been inspired by the pet owl that used to fly around Derain's Parisian studio in the early 1920s. While the brilliantly coloured parrot in Derain's large Fauve painting, ‘Dance’, 1907 (Fridart Foundation, repr. Lee 1990, pp.6–7 in col.), had expressed a sense of joy and freedom, the more domestic, quieter creature in T04923 can be seen as expressing intelligence, and the gift of imitation. Its presence was a reminder of the painter's work of imitating appearances (underscoring the importance of this symbol, Derain appears to look at the parrot rather than at his canvas or the objects before him).

There were a number of animals in Derain's home at Chambourcy, including ducks and geese, and a peacock. According to Lee (1990, p.134), the peacock in T04923 plays ‘its traditional role as a symbol of both worldly glory and the mystical glory in paradise’. The Derains also kept cats, though the cat next to Alice (which was a dark tabby rather than a purely black cat), should perhaps be seen as a symbol of arcane knowledge, and contact with mysterious forces. Derain had represented a cat in his c.1919–20 portrait of Alice (T03368) and had also included one in an engraved self-portrait of c.1929 (‘Le Fumeur’, in a suite of prints entitled ‘Le Bestiaire’).

In size and scale of ambition T04923 appears related to a number of large-scale works executed in the late 1930s. These include such pastoral scenes as ‘The Surprise’, 1938 (Art Salon, Takahata, Osaka City, repr. Lee 1990, p.67 in col.), and ‘The Clearing, or Picnic Lunch’, 1938 (Museé du Petit Palais, Geneva, repr. ibid., in col.) as well as the huge ‘The Golden Age’, c.1939 (Museé national d'art moderne, Paris, p.82 in col.), which may have been intended as a wall decoration or as a study for a tapestry (its design and tonality are particularly reminiscent of sixteenth-century tapestries). It was after working on such grand-scale mythical subjects that Derain felt moved to make in T04923 a rather more personal statement about his vision of art.

T04923 is thought to have been painted c.1939. It certainly could not have been completed later than February 1940, for the dealer Pierre Matisse arranged for it and other recent works to be shipped from France in March of that year for an exhibition at his New York gallery in April. In a letter dated 4 February 1941 Matisse explained to the director of the Cincinatti Art Museum that he had first seen the paintings in Derain's studio in December 1939 after his demobilisation from the French army. ‘The pictures were magnificent’, he continued, ‘and I would have had them shipped right away to the United States if they had been completely finished’. It is not clear under what terms the works were exported. An advantage for Derain of this arrangement was that it provided a ‘safe haven’ for his works during the war. However, it is not clear whether he intended all the works to be offered for sale. The exhibition André Derain: Paintings from 1938 was arranged for the benefit of the American Friends of France, and an admission fee was charged. While some of the works in this show were subsequently exhibited by Pierre Matisse in 1944 in a straightforward selling exhibition, T04923, as well as a few other works, were not. It is therefore conceivable that Derain wished to retain ownership of it. (An installation photograph of the exhibition, showing T04923 in a different frame from the one it currently possesses, is reproduced in André Derain in North American Collections, exh. cat., Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery, University of Regina 1982, p.24. This would have been added by Pierre Matisse, as Geneviève Taillade confirmed in conversation with the compiler on 6 August 1992 that Derain would not have had such a large painting framed himself.)

In a favourable review of the New York exhibition, Doris Brian (1940, p.10) wrote about T04923:

A sort of light-hearted keystone of the ensemble is a happy group self-portrait in terracotta tones highlighted with bright greens and blues, ‘La Famille’ on which the paint is barely dry. Crammed full of his trademarks - the head of the niece who so often serves as his model, the compotier with translucent grapes and firm pears, the impudent little vase of flowers - it shows the French bonhomme working with his family and chattels around him. The frown of concentration on his face is not without good humor, for he looks, as does the parrot who perches atop his easel, as if he might utter a gruff wittisism at any moment. Not the most finished work that the artist has given us (note the casual execution of the napkin in comparison with the treatment of similar bits of still life in some of the other paintings), it is, nevertheless, a sound and clever exhibition piece.

T04923 was not sold at this exhibition, and remained in the possession of Pierre Matisse. When reproduced in Malcolm Vaughan's monograph in 1941, it was credited as belonging to the Pierre Matisse Gallery. It seems likely that it remained in America until after it was exhibited in Chicago in 1947, and returned to Derain's home sometime before 1950. It probably remained in a packing case or in the studio: according to Geneviève Taillade, it was not hung in the house. The work, which had been known simply as ‘The Family’, was given its current title at the time of the retrospective exhibition held in Derain's memory in December 1954.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- muse(13)

- domestic(1,795)

-

- living room(292)

- eating and drinking(409)

-

- eating(230)

- reading(400)

- fine arts and music(3,982)

-

- easel(81)

- fruit - non-specific(173)

- individuals: female(1,698)

- self-portraits(888)

- French(436)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist - non-specific(2,109)

- artist, painter(2,545)

- artist, sculptor(1,668)

You might like

-

Pierre Bonnard The Table

1925 -

André Derain Landscape near Barbizon

c.1922 -

Duncan Grant Girl at the Piano

1940 -

Victor Pasmore Lamplight

1941 -

Walter Richard Sickert The Little Tea Party: Nina Hamnett and Roald Kristian

1915–16 -

Giorgio de Chirico The Painter’s Family

1926 -

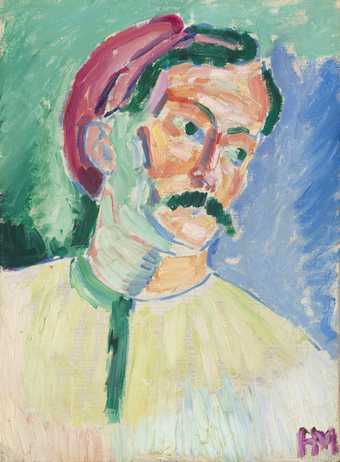

Henri Matisse André Derain

1905 -

Henry Tonks Sodales - Mr Steer and Mr Sickert

1930 -

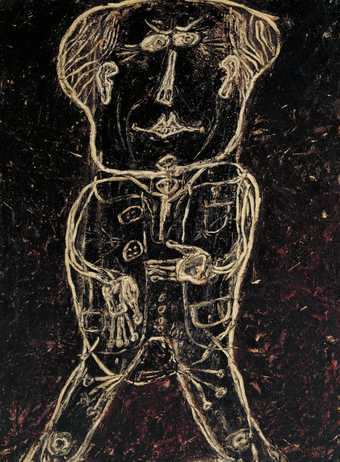

Jean Dubuffet Monsieur Plume with Creases in his Trousers (Portrait of Henri Michaux)

1947 -

Fernand Léger The Acrobat and his Partner

1948 -

James Cowie An Outdoor School of Painting

1938–41 -

André Derain Still Life

c.1938–43 -

Raoul Dufy The Kessler Family on Horseback

1932 -

George Warner Allen Picnic at Wittenham

1947–8 -

Cecil Collins The Artist and his Wife

1939