Not on display

- Artist

- Salvador Dalí 1904–1989

- Original title

- Métamorphose de Narcisse

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 511 × 781 mm

frame: 820 × 1092 × 85 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1979

- Reference

- T02343

Summary

This painting is Dalí's interpretation of the Greek myth of Narcissus. Narcissus was a youth of great beauty who loved only himself and broke the hearts of many lovers. The gods punished him by letting him see his own reflection in a pool. He fell in love with it, but discovered he could not embrace it and died of frustration. Relenting, the gods immortalised him as the narcissus (daffodil) flower. For this picture Dalí used a meticulous technique which he described as 'hand-painted colour photography' to depict with hallucinatory effect the transformation of Narcissus, kneeling in the pool, into the hand holding the egg and flower. Narcissus as he was before his transformation is seen posing in the background. The play with 'double images' sprang from Dalí's fascination with hallucination and delusion.

This was Dalí's first painting to be made entirely in accordance with the paranoiac critical method, which the artist described as a 'Spontaneous method of irrational knowledge, based on the critical-interpretative association of the phenomena of delirium' (The Conquest of the Irrational, published in The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí, New York 1942). Robert Descharnes noted that this painting meant a great deal to Dalí, as it was the first Surrealist work to offer a consistent interpretation of an irrational subject.

The artist said to Descharnes of this picture:

A painting shown and explained to Dr. Freud.

Pedagogical presentation of the myth of narcissism, illustrated by a poem written at the same time.In this poem and this painting, there is death and fossilization of Narcissus.

The poem to which Dalí referred was published in 1937, in a small book by the artist entitled Metamorphosis of Narcissus. The book also contains two explanatory notes printed facing a colour reproduction of the painting, the first of which reads:

WAY OF VISUALLY OBSERVING THE COURSE OF THE METAMORPHOSIS OF NARCISSUS REPRESENTED IN THE PRINT ON THE OPPOSITE PAGE:

If one looks for some time, from a slight distance and with a certain 'distant fixedness', at the hypnotically immobile figure of Narcissus, it gradually disappears until at last it is completely invisible.

The metamorphosis of the myth takes place at that precise moment, for the image of Narcissus is suddenly transformed into the image of a hand which rises out of his own reflection. At the tips of its fingers the hand is holding an egg, a seed, a bulb from which will be born the new narcissus - the flower. Beside it can be seen the limestone sculpture of the hand - the fossil hand of the water holding the blown flower.

When he met Sigmund Freud in London in 1938, Dalí took this picture with him as an example of his work, as well as a magazine containing an article he had written on paranoia. Freud wrote the following day to Stefan Zweig, who had introduced them, that 'it would be very interesting to explore analytically the growth of a picture like this'.

Further reading:

Tate Gallery 1978-80 Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, London 1981, pp.85-9, reproduced p.85

Robert Descharnes, Gilles Néret, Salvador Dalí: The Paintings, 2 volumes, Köln 1994, pp.288-9, 299, 757, reproduced pl.645 in colour

Dawn Ades, Dalí, revised edition, London 1995, pp.132-3, reproduced p.131 in colour

Terry Riggs

March 1998

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

According to Greek mythology, Narcissus fell in love with his own reflection in a pool. Unable to embrace the watery image, he pined away, and the gods immortalised him as a flower. Dalí shows this metamorphosis by doubling a crouching figure by the lake with a hand clutching an egg, from which the narcissus flower sprouts. When this painting was first exhibited it was accompanied by a long poem by Dalí. Together, the words and image suggest a range of emotions triggered by the theme of metamorphosis, including anxiety, disgust and desire.

Gallery label, October 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Salvador Dalí 1904–1989

Metamorphosis of Narcissus

Métamorphose de Narcisse

1937

Oil paint on canvas

510 x 780 mm

Inscribed ‘Gala Salvador Dalí 1937’ lower right

Purchased from the Edward James Foundation (Grant-in-Aid) 1979

T02343

Ownership history:

Purchased from the artist by Edward James, Chichester 1937; Edward James Foundation on loan to Tate from 1958 until acquired in 1979.

Exhibition history:

When Dalí visited the aging psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) in London in July 1938, he brought one painting with him: Metamorphosis of Narcissus. Freud wrote to the Austrian-born writer Stefan Zweig (1881–1942) the following day:

until now I was inclined to regard the Surrealists – who seem to have chosen me as their patron saint – as 100% mad (let’s say 95%, as with alcohol). This young Spaniard, with his ingenuous fanatical eyes and his undeniable technical mastery, has suggested to me a different appreciation. In fact, it would be very interesting to explore analytically the creation of such a painting.1

Dalí began painting Metamorphosis of Narcissus in Zürs, in the Austrian Alps, in the spring of 1937. Its subject is based directly on the Greek myth of Narcissus, a beautiful boy who was highly sought after by would-be suitors, but too proud to offer his love in return. According to the version of the story retold in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (c.8 AD), one of Narcissus’s rejected lovers invoked the goddess Nemesis to punish Narcissus for his arrogance. Nemesis complied, and one day, when Narcissus bent down to drink from a clear pool of water, he caught a glimpse of his own reflection and was completely overcome with love. He tried in vain to embrace his reflection, and when his love could not be reciprocated, he fell into such despair that he beat his breast until he died. In his place bloomed a lovely white flower with a yellow centre: the narcissus.

Given Dalí’s fascination with transformation – evidenced extensively in his double-image paintings, such as Mountain Lake 1938 (Tate T01979) – it is possible to understand why the Narcissus myth was so stirring for him. However, Metamorphosis of Narcissus differs from many of his other double-image paintings in that, rather than seeing multiple images hidden within one ambiguous figure – a reclining woman who is also a horse and a lion as well, for example – the subject itself is doubled. A crouching Narcissus sits on the left side of the painting, resting his head on his knee as he peers into the lake at his reflection, while on the right hand side of the painting the form of his body becomes an ossified hand, the fingertips of which grasp an egg – the bulb from which the narcissus flower blooms.2 Thus, Dalí presents both Narcissus’s self-obsession and its disastrous outcome in the same space, but as two distinct figures. His rationale for this has not been widely discussed, though it evinces his sophisticated awareness of optical phenomena. In 1937 he wrote:

If one looks for some time, from a slight distance and with a certain ‘distant fixedness’, at the hypnotically immobile figure of Narcissus, it gradually disappears until at last it is completely invisible. The metamorphosis of the myth takes place at that precise moment, for the image of Narcissus is suddenly transformed into the image of a hand which rises out of his own reflection … Beside it can be seen the limestone sculpture of the hand – the fossil hand of the water holding the blown flower.3

Dalí’s fascination with ‘optical illusions’ has received considerable critical attention, yet little of this has been focused on his comments on how he intended Metamorphosis of Narcissus to be viewed.4 In his description, Dalí capitalises on a familiar phenomenon, namely if one stares at a fixed point for a long duration, objects appear to vanish. The effect is due to the perceptual need for constant movement – tiny saccades, or subtle jerky movements – that perpetually refocus the eye and change what the viewer sees. The optic nerve is designed to ignore images that are static on the retina. The central focus of the eye is least affected, which is why peripheral objects disappear first, but in theory, if the subject of concentration becomes a sufficiently stable retinal image, it, too, will begin to disappear from sight.5 Dalí recommended concentrating on the figure of Narcissus until it transforms into a hand emerging from the water and finally disappears, for it is at that precise moment that ‘metamorphosis’ occurs: Narcissus vanishes, leaving behind the stony hand and blooming flower.

In conjunction with Metamorphosis of Narcissus Dalí wrote an eponymous poem composed, allegedly, in order to amplify the effect of the painting.6 The poem was published in 1937 in a limited edition by Éditions surréalistes, and shortly thereafter the English poet and collector Edward James (1907–1984) undertook an English translation, which was published through the Julien Levy Gallery in New York.7 The full text of the poem is given here:

Under the split in the retreating black cloud

the invisible scale of spring

is oscillating

in the fresh April sky.

On the highest mountain,

the god of the snow,

his dazzling head bent over the dizzy space of reflections,

starts melting with desire

in the vertical cataracts of the thaw

annihilating himself loudly among the excremental cries of minerals,

or

between [sic] the silences of mosses

towards the distant mirror of the lake

in which,

the veils of winter having disappeared,

he has newly discovered

the lightning flash

of his faithful image.

It seems that with the loss of his divinity the whole high plateau

pours itself out,

crashes and crumbles

among the solitude and the incurable silence of iron oxides

while its dead weight

raises the entire swarming and apotheosic

plateau from the plain

from which already thrust towards the sky

the artesian fountains of grass

and from which rise,

erect,

tender,

and hard,

the innumerable floral spears

of the deafening armies of the germination of the narcissi.

Already the heterosexual group, in the renowned poses of preliminary expectation, conscientiously ponders over the threatening libidinous cataclysm, the carnivorous blooming of its latent morphological atavisms.

In the heterosexual group,

in that kind date of the year

(but not excessively beloved or mild),

there are

the Hindou

tart, oily, sugared

like an August date,

the Catalan with his grave back

well planted

in a sun-tide,

a Whitsuntide of flesh inside his brain,

the blond flesh-eating German,

the brown mists

of mathematics

in the dimples

of his cloudy knees, there is the English woman,

the Russian,

the Swedish women,

the American

and the tall darkling Andalusian,

hardy with glands and olive with anguish.

Far from the heterosexual group, the shadows of the avanced [sic] afternoon draw out across the countryside, and cold lays hold of the adolescent’s nakedness as he lingers at the water’s edge.

When the clear and divine body of Narcissus

leans

down to the obscure mirror of the lake,

when his white torso folded forward

fixes itself, frozen,

in the silvered and hypnotic curve of his desire,

when the time passes

on the clock of the flowers of the sand of his own flesh,

Narcissus loses his being in the cosmic vertigo

in the deepest depths of which

is singing

the cold and Dyonisiac siren of his own image.

The body of Narcissus flows out and loses itself

in the abyss of his reflection,

like the sand glass that will not be turned again.

Narcissus, you are losing your body,

carried away and confounded by the millenary reflection of your

disappearance

your body stricken dead

falls to the topaz precipice with yellow wreckage of love,

your white body, swallowed up,

follows the slope of the savagely mineral torrent

of the black precious stones with pungent perfumes,

your body ...

down to the unglazed mouths of the night

on the edge of which

there sparkles already

all the red silverware

of dawns with veins broken in ‘the wharves of blood’.

Narcissus,

do you understand?

Symmetry, divine hypnosis of the mind’s geometry, already fills up your

head,

with that incurable sleep, vegetable, atavistic, slow

Which withers up the brain

in the parchment substance

of the kernel of your nearing metamorphosis.

The seed of your head has just fallen into the water.

Man returns to the vegetable state

by fatigue-laden sleep

and the gods

by the transparent hypnosis of their passions.

Narcissus, you are so immobile

one would think you were asleep.

If it were a question of Hercules rough and brown,

one would say: he sleeps like a bole [sic]

in the posture

of an Herculean oak.

But you, Narcissus,

made of perfumed bloomings of transparent adolescence,

you sleep like a water flower.

Now the great mystery draws near,

the great metamorphosis is about to occur.

Narcissus, in his immobility, absorbed by his reflection with the digestive slowness of carnivorous plants, becomes invisible.

There remains of him only

the hallucinatingly white oval of his head,

his head again more tender,

his head, chrysalis of hidden biological designs,

his head held up by the tips of the water’s fingers,

at the tips of the fingers

of the insensate hand,

of the terrible hand,

of the excrement-eating hand,

of the mortal hand

of his own reflection.

When that head slits

when that head splits

when that head bursts,

it will be the flower,

the new narcissus,

Gala –

my narcissus.8

As discussed in depth by the art historian David Lomas, many of the elements in Dalí’s poem figure in the painting: the ‘god of snow’, for example, is a third Narcissus figure nestled among the background’s mountains, while the ‘heterosexual group’ – perhaps Narcissus’s would-be suitors – is identifiable in the mid-ground of the painting, foiling Narcissus’s self-imposed isolation.9

Lomas has also convincingly explored the homoerotic content of Dalí’s painting from the basis of the Narcissus myth itself, citing Ovid’s Metamorphoses: ‘many men, many girls desired [Narcissus]; but (there was in his delicate beauty so stiff a pride) no men, no girls affected him’.10 Lomas makes a convincing link with Caravaggio’s (1571–1610) Narcissus c.1600 (Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome) and the treatment of the ‘phallic knee’, which Dalí ‘goes one better’ by twinning with its reflection, creating what might be read as buttocks.11

The last line of the poem, in which Dalí identifies Gala as ‘his narcissus’, is compelling. Lomas notes that there is a less popular variant of the Narcissus myth, cited by Pausanias in his second-century Guide to Greece, in which the tragic hero falls in love with his own reflection not because he recognises it as himself but because he sees in his own face the visage of his beloved, deceased twin sister.12 In identifying his wife Gala as ‘his narcissus’, Dalí may be fashioning her as his double – a possibility advanced further by his tendency to merge his name with hers. With this in mind, it might be significant that Metamorphosis of Narcissus, like many other works of the period, is signed, ‘Gala Salvador Dalí’.

Dalí began Metamorphosis of Narcissus by priming a fine linen canvas with lead white pigment in linseed oil. Infrared radiography (IRR) reveals that Dalí drew elements of the composition, probably in more than one drawing medium at different stages of the painting’s progression. According to Patricia Smithen, Head of Painting Conservation at Tate:

One medium is quite granular, with particles caught up in the surrounding paint. This feature is seen in the small figure group in the centre of the painting and in the checkerboard figure. There are dotted lines on the edges of the checkerboard squares and more dotted lines in the red ground below the checkerboard. The dots may be caused by the pencil or ink skipping lightly over the canvas. At the bottom of the checkerboard are also small measurement lines – perhaps squaring the area for perspective. There are some areas of shading or hatching visible, notably in the area next to the head of the large kneeling figure. This large figure appears to have been outlined with additional shading and hatching in graphic pencil, with the paint following the contours of bits of drawing that are visible with IRR ... There are a few extant sketches for this work ... But no full drawings of the composition exist. It appears to have been worked up in stages, using different media: graphite pencil and possibly charcoal or pen and ink.13

Edward James, who spent time with Dalí and Gala at Zürs (where Dalí started the painting) and who had already arranged to purchase the picture upon its completion, noted the existence of preparatory drawings in a letter to the gallerist Julien Levy in response to Levy’s request to purchase the painting from him:

For the moment, seeing that he has done nothing else quite like this – and in view of the fact that I watched it steadily grow: for I was there when the canvas had its first pencil mark put on it, and even saw the preliminary sketches for the picture before the big canvas was begun at all: I feel such an attachment for it that I could not bear to re-sell it to anybody without having at any rate contemplated it for a bit in its finished state.14

In 1945 the short-lived surrealist journal Vrille published a fine, very finished drawing of the central figure, which may have been one of these preliminary sketches referred to by James.15 The drawing is remarkable for its subtle use of the double image: in the finished painting the brooding Narcissus and the bony hand bearing the egg and flower are separate forms, but in this drawing they are combined – the left leg of Narcissus reads also as a thumb and his arm as a finger, the two delicately holding the head/egg.

Smithen also notes that Dalí employed two distinct artistic styles in his painting. For the figures and areas where there is underdrawing, he used carefully applied brushstrokes, but the stones, cliffs, trees and foliage were painted in a considerably looser style. According to Smithen:

It seems clear that Dalí [had] more trouble with the right quarter of the composition than the rest. In this area are the most changes, alterations and underdrawing which does not match the painted surface. The checkerboard, red and green ground beneath it and the dog have all been worked in one of these ways. In comparison, the rest of the composition shows no such changes or alterations.16

Smithen further added that Dalí used a much wider range of pigments in Metamorphosis of Narcissus than is generally found on a single painting: ‘vermilion, Mars red, madder on an aluminium-based substrate, cadmium orange, cadmium yellow, chrome yellow, Mars yellow, cobalt blue, cerulean blue, viridian, bone black, Mars brown, sienna, lead white and zinc white.’17

A final technical detail concerns the greyhound on the right, which does not figure in Dalí’s poem. Conservators’ studies reveal that the underdrawing for the greyhound was made on top of the surrounding green ground, indicating that it was a later addition to the composition. This is confirmed in a letter from Dalí to Edward James, dated 15 June 1937:

Your little picture will surprise you … The finished Narcissus has become much more important now with the apparition of the dog which is eating the cutlets … this dog which serves as a union with the next myth of Dionysus is very good in front of this savage landscape … nothing could grow in this sterile land.18

The final touch to the painting would not be the dog, however, but the ants: according to the results of ultraviolet examination by Tate conservators, these ants, as well as many other small black flourishes throughout the composition, lie on top of even the resin varnish.19

Elliott H. King

December 2007

Supported by The AHRC Research Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacies.

Notes:

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- desire(149)

- frustration(111)

- love(516)

- narcissism(9)

- repetition(391)

- transformation(186)

- fine arts and music(3,982)

-

- plinth(156)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- crouching(276)

- hand(602)

- crowd(646)

- birth to death(1,472)

You might like

-

André Masson Ibdes in Aragon

1935 -

Joan Miró Women and Bird in the Moonlight

1949 -

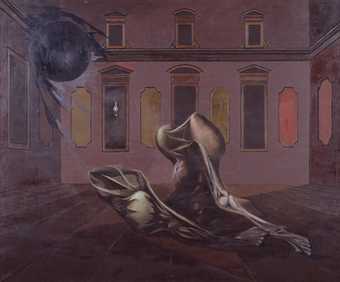

Peter Rose Pulham L’Hôtel Sully, Courtyard with Figures

?1944–5 -

Hans Bellmer Peg-Top

c.1937–52 -

Salvador Dalí Forgotten Horizon

1936 -

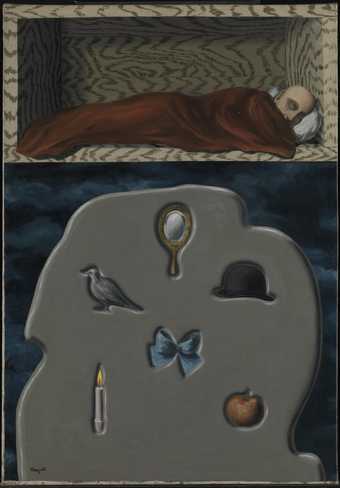

René Magritte The Reckless Sleeper

1928 -

Joan Miró Painting

1927 -

Salvador Dalí Autumnal Cannibalism

1936 -

Salvador Dalí Mountain Lake

1938 -

Gordon Onslow-Ford A Present for the Past

1942 -

Salvador Dalí Lobster Telephone

1938 -

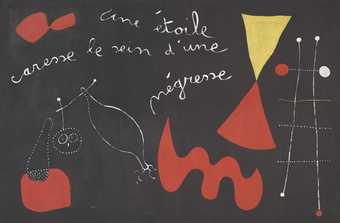

Joan Miró A Star Caresses the Breast of a Negress (Painting Poem)

1938 -

Joan Miró Message from a Friend

1964 -

Yves Tanguy Azure Day

1937 -

Joan Miró Head of a Catalan Peasant

1925