In Tate Britain

- Artist

- Ithell Colquhoun 1906–1988

- Medium

- Oil paint on board

- Dimensions

- Support: 914 × 610 mm

frame: 1004 × 706 × 69 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1977

- Reference

- T02140

Display caption

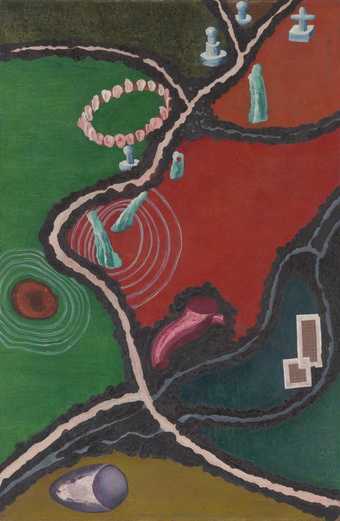

The title of this work refers to the female monster who, according to ancient Greek mythology, inhabited a narrow channel of water and fed on passing sailors. Colquhoun explained that the image could be understood in two ways, both as a seascape and as an image of her own body. ‘It was suggested by what I could see of myself in a bath…it is thus a pictorial pun, or double-image’. The rock formations can also be seen as knees, with seaweed in place of pubic hair. This work was painted at a time when Colquhoun was exploring surrealist ideas such as the double image.

Gallery label, January 2019

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Ithell Colquhoun 1906-1988

T02140 Scylla

1938

Oil on board

914 x 610 (36 x 24)

Inscribed on back in black ink: 'No:4 SCYLLA | ITHELL COLQUHOUN | 49 BRITISH GROVE W14' top centre; in fibremarker 'ITHELL COLQUHOUN | SCYLLA (MEDITERRANEE) | 1938' centre; in pencil upside down 'ITHELL COLQUHOUN', bottom centre and 'AL3438' b.r.; removed printed label with artist's address, inscribed in ball-point pen '12a' (circled); board stamped 'Roberson & Co | Long Acre London' top centre, 'C Roberson & Co Ltd | 101-104 Park Street, London N1', centre, and 'TACHET | BREVETE | A PARIS' bottom centre

Purchased from the artist through the Newlyn-Orion Gallery, Penznace (Knapping Fund) 1977

Exhibited:

Ithell Colquhoun and Roland Penrose, Mayor Gallery, London, June 1939 (4, as 'Scylla (Méditerranée)')

Ithell Colquhoun: Retrospective Exhibition of Oil Paintings, Newlyn Art Gallery, Penzance, Oct. 1961 (14)

Britain's Contribution to Surrealism in the 30s and 40s, Hamet Gallery, London, Nov. 1971 (28)

Ithell Colquhoun: An Exhibition of Surrealist Paintings and Drawings from 1930-50, Leva Gallery, London, Oct. - Nov. 1974 (9, repr. [p. 6])

Hampstead in the Thirties: A Committed Decade, Camden Arts Centre, London, Nov. 1974 - Jan. 1975 (18, as 'Scylla (Méditerranée)')

Ithell Colquhoun: Surrealism, Paintings, Drawings, Collages 1936-76, Newlyn-Orion Galleries, Penzance, 1976 (3)

Ithell Colquhoun: Paintings and Drawings 1930-40, Parkin Gallery, London, Nov.-Dec. 1977 (17)

Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, Hayward Gallery, London, Jan.-March 1978 (14.10)

Contrariwise: Surrealism and Britain 1930-1986, Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea, Sept.-Nov. 1986, Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, Nov.-Jan. 1987, Polytechnic Gallery, Newcastle, Jan.-Feb., Mostyn Art Gallery, Llandudno, Feb.-April (45, repr. p.36)

Literature:

Jan Gordon, 'Art and Artists', The Observer, 18 June 1939

Ithell Colquhoun: Paintings and Drawings 1930-40, exh. cat, Parkin Gallery, London 1977, [p.3]

Dawn Ades, Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, exh. cat., Hayward Gallery, London 1978, p.359

Tate Gallery Acquisitions 1976-8, London 1978, pp.41-2, repr.

Dawn Ades, 'Notes on Two Women Surrealist Painters: Eileen Agar and Ithell Colquhoun', Oxford Art Journal, vol.3, no.1, April 1980, p.40, repr. p.38, fig.2

Ithell Colquhoun, 'Letters: Women in Art', Oxford Art Journal, vol.4, no.1, July 1981, p.65

Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, London 1985, pp.126-8, repr., p.104, pl.88

David Brown, 'Obituary', Independent, 26 April 1988, p.19

Dawn Ades, Surrealism in the Collection, Tate Gallery Liverpool, 1988, p.18, repr. in col.

Fiona Bradley, Surrealism, London 1997, p.51, repr. in col. p.50

Matthew Gale, Dada and Surrealism, London 1997, p.347, repr. p.346, pl.188 (col.)

Also reproduced:

Ithell Colquhoun, 'The Volcano', London Bulletin, no.17, June 1939, p.15

Newlyn Orion Art Gallery Newsletter, 1977, p.4

Ithell Colquhoun combined illusionism and transmogrification in Scylla

which accommodated layers of suggestive interpretations. The painting is one of a group of seven works all subtitled Méditerranée, the completion of which straddled a crucial moment in her career as she made the transition from what she termed her 'magic realism' to Surrealism.1

By its dating, Scylla

appears to be the earliest of this group (the others being dated to 1939), and in many ways it is the most introspective.

The title refers most immediately to the monster with six heads on elongated necks of Homer's Odyssey. In narrows - usually identified with the Straits of Messina - Odysseus and his crew had to pass between Scylla (who ate six of the men) and the whirlpool Charybdis. Colquhoun's image of a boat approaching inward-leaning rocks painted in sandy ochres and pinks evokes this narrow passage. To this well known source may be added the myth of Scylla the daughter of King Nisus of Megara, who, for the love of the invading King Minos, pulled the hair from her father's head which protected his life. This story is given in James George Fraser's The Golden Bough,2

under the sub-heading 'Idea of the external soul', and it is likely that the painter was aware of it, as a copy of the book remains amongst her collection of esoteric literature.3

In Scylla, Colquhoun may be seen to adapt the orthodoxy of the mythological and religious themes typical of figure compositions at the Slade.

The title and its allusions partially disguise more personal associations. In response to a Tate Gallery enquiry as to whether the image was 'the result of a dream', Colquhoun cited the Homeric myth, stating: 'It was suggested by what I could see of myself in a bath - this, with a change of scale due to "alienation of sensation" became rocks and seaweed. It is thus a pictorial pun, or double-image in the Dal¡esque sense - not the result of a dream but of a dreamlike state'.4 There is little difficulty in identifying the derivation of the rocks from her knees and the seaweed from pubic hair, and the turbulence of the latter may evoke the snake-like necks of Scylla. Toni del Renzio, the artist's husband in the 1940s, has tentatively suggested that this source may have been revealed at the time of the painting's first showing in 1939.5

Whatever the case, a sketchbook drawing6

survives which appears to have been made in the bath; looking down on the body, it shows a more seated pose with the knees splayed and legs crossed at the shins. The rather uncertain linear style suggests that this considerably predates Scylla, an impression supported by the sketchbook which was from a supplier in Cheltenham (Norman, Sawyer & Co Ltd.), where Colquhoun studied before going to the Slade; an identical green-covered sketchbook contains comparable figure drawings dated October 1927.7

Even if Colquhoun's use of this unusual self-portraiture went back a decade, it is notable that two commentators have drawn comparisons between Scylla

and Frida Kahlo's exactly contemporary What the Water Gave Me, 1938 (Tomas Fernandez Marquez, Mexico City).8

The latter also shows the painter's legs in the bath, although augmented by floating images relating to her personal life. Colquhoun herself sent the Tate a poem by Simon Green in which the comparison with Kahlo is made (letter, 9 June 1977, Tate Gallery Cataloguing Files),9

while Toni del Renzio commented on this coincidence.10

It is just possible that the Mexican's painting was known to Colquhoun through Surrealist circles, but the mythologised eroticism of Scylla

is quite distinct from Kahlo's sense of autobiography.

These sources disguise a further still more sexually charged allusion in Scylla. Through transformation into rocks, the knees have become ribbed and layered, but they maintained a fleshy character in form and in colour. Dawn Ades has seen them as 'transformed into a phallic landscape',11 but they also combine to establish an oval opening which is expressly vaginal. Significantly, the painter commented upon Ades's article by noting 'Scylla in my view is primarily a feminine symbol but I suppose one could see it as phallic as well'.12 Such a recognition of the femininity of the image may inform the selection of the title, which allows for a wilful - even aggressive - feminine sexuality. As Fiona Bradley has remarked, by allusion to the clashing rocks of another ancient myth (the Voyage of the Argo), the knees 'are ready to clash together at the approach of the threatening phallic boat'.13 Thus the passive image is highly charged and, in the suggestive penetration of forms, may be compared to Barbara Hepworth's slightly earlier and initially equally innocuous sculpture Two Forms, 1933 (Tate Gallery T07123).

Although Ades remarked that Scylla

was relatively isolated in Colquhoun's work as an 'example of explicit sexual imagery',14 it is now clear that this tendency was more widespread. The vagina form was treated again in the more immediately sexual Tree Anatomy, 1942 (Mr and Mrs Michael Pruskin).15

Furthermore, such sexuality was present to varying degrees in other works, from the suggestively flaccid Cucumber

1939 (present whereabouts unknown)16

to the labelled and pollarded limbs of The Pine Family, 1941 (private collection).17

William Johnstone recalled Colquhoun having to remove a 'pornographic' work from the Leicester Galleries in the 1940s, which she replaced by another 'worse than the first'.18

This element of deliberate provocation is also evident in the painter's related writings: Scylla

was first published as an illustration for 'The Volcano',19 a dreamlike narrative which evokes deliberately Freudian references for an island volcano and lighthouse. Such associations, explicitly linked to the Mediterranean through the subtitle of the series of paintings, seem to be rooted in personal experience. According to Toni del Renzio,20

Colquhoun had an affair with a fisherman on a visit to Corsica in 1937-8 which left a profound effect on her and may have been the impetus behind the Méditerranée

series. As well as the partial self-portrait in Scylla, the group included two male nudes. One was the portrait of a kneeling youth Beau Gosse, 1939 (private collection);21

in one hand he holds a thorn with which he seems to have wounded his other wrist. In the second painting, Gouffres Amers, 1939 (Glasgow University)22

a reclining body is composed from enlarged corals and seaweeds; the means are reminiscent of the seventeenth century artist Giuseppe Archimboldo but the effect is of mortal decay. As Chadwick has shown of this work: 'the title and inspiration come from Baudelaire's poem depicting "le navire glisant sur les gouffres amers" ("the ship slipping into the bitter whirlpool")'.23 Thus the imagery and the details complement those used in Scylla. Although the extent of an autobiographical interpretation for the series is difficult to assess, the symbolism of another painting, Le Phare

('The lighthouse'), 1939 (private collection)24

- which shows a flower pierced by an arrow but rooted in a panoramic view of a port - serves to reinforce the suggestion of a cycle of overwhelming love. This may be related to what the French Surrealists termed 'l'amour fou', the title of André Breton's book of 1937.

As Colquhoun stated in 1977, her paintings used the 'double-image' developed by Salvador Dal¡. The Spanish painter had termed this approach his 'paranoiac-critical method', by which two or more independent images were simultaneously discernible within the same forms. As a woman artist, Colquhoun's images of the body necessarily modified the use of this method. Whitney Chadwick has remarked on the painter's 'almost-mocking parodies of the Surrealist obsession with eroticism as the basis of the metamorphic process',25 and Dawn Ades has also seen them as parodying 'a specific form of sexual imagery exploited by the Surrealists, that which treats landscape metaphorically as a woman'.26 Both art historians thus view Colquhoun's contribution as a specifically female revision of the predominantly male erotic paradigm within Surrealism. In Scylla

in particular, she may be seen as having presented a reversal of the orthodox female nude as object by laying claim to her own sexuality or, as Fiona Bradley has remarked, by making a painting which reasserts 'a woman's right to her own body'.27 In the early 1940s, as Chadwick has noted,28

the painter sought to reconcile this conflict between the sexes in the image of 'the hermaphrodite whole' in texts such as 'The Water Stone of the Wise' (New Road, 1943) which were informed by her occult and esoteric studies.

Colquhoun's academic artistic training, which facilitated the achievement of the desired multiple illusions, was also reflected in the way in which Scylla

was made. It was painted on a prepared plywood board with the front edges chamfered and the back edges rounded and it remains in good condition. The face had a coat of gesso and the back a sealing coat of grey paint. The different addresses of the two Roberson stamps on the back indicate that it was purchased around the time of the company's move in 1937-8,29

a suggestion confirmed by the artist's own recollection that the panel was sold as 'old stock'.30 The handling of the paint is generally smooth and the artist's account of adding poppy seed oil to Winsor and Newton paints is confirmed by analysis; no varnish was used. At the time Colquhoun preferred hard supporting surfaces 'as near to that of polished ivory as possible' and added of her technique: 'I need a line to work to (Blake's "bounding outline"); that means a full-sized detailed drawing afterwards traced. Then I put on the opaque colours very smoothly and finally the glazes, if any, with the transparent colours'.31 In fact the very deliberate brushstrokes are clearly discernible, following the contours of the forms and abutting the 'bounding lines'; the green of the water was applied as a glaze, which appears to have been lifted off again in areas (such as at the lower left). Nearly forty years later she told the Tate that she had 'a full-size cartoon in charcoal of Scylla

... [and] I feel sure that I made colour notes also'.32

Since then a coloured drawing with an accompanying inscription, 'Colour note for SCYLLA

(1938)',33 has been given to the Tate Gallery. Slightly more obviously figurative in inspiration, it shows the main details drawn in pencil, with the pair of knee/rocks washed in pink/raw sienna watercolour against a blue sky and green sea. The details extend slightly to the left of an imposed rectangle noted at the left as '2.7 x 4.4' (i.e. 2 7/10 x 4 2/5 in.; 68 x 112 mm). The area within this rectangle was halved and quartered, and diagonals drawn which secured the eighths; the lines are numbered along the edge 1-7 (left to right and top to bottom).

While this geometry has been imposed on the original image, its purpose seems to be twofold. First, it tightened the compositional structure; so that the meeting of the knee/rocks falls on the half-way point and converges lower down on the three-eighths line. Second, although it did not directly give rise to the Golden Section, it served as the basis for the further imposition of Golden Section geometry (the ratio 1:1.618), worked out on the drawing in red ball-point pen. Thus the sea's horizon is located at that proportion of the height of the composition (just below five eighths of the way up). The Golden Rectangles thus created at the top and bottom of the composition are each divided again in red ball-point into smaller units which all bear the algebraic symbol for the golden section [Theta]. Colquhoun has arranged these subdivisions in order to retain the emphasis of the composition to the left, and used the three-eighths line as an approximation of the Golden Section of the width in order to locate the apex of the left knee/rock and the sex/sea-weed.

Almost all of this compositional geometry was transferred to the final image, where the correct proportions were achieved by reducing the width by the enclosing grey strips. The artist specified that this was their purpose.34

The intervening width (c.565 mm / 22 1/4 in.), like the level of the horizon, is the Golden Section of the height. This interest apparently resulted from the painter's reading of Jay Hambidge's The Elements of Dynamic Symmetry

(1926) in c.1938-9.35

Only the boat and the waterline were significantly changed. A small version of the boat, visible in its entirety in the drawing and attached to the centre line, was reduced to the glimpse of the prow in the painting shifted to the left of centre. The waterline has been angled more steeply between the main forms, making the spatial sense more convincing.

The painting's good condition belies its rather chequered history. A draft letter to 'Mr Nash' - probably John - shows that Colquhoun proposed sending Scylla

to the London Group, but sought advice as she did not 'care to submit it unless it has a good chance of being well hung'.36 She had shown Corte: Corsica

(whereabouts unknown) at the London Group in 1937, but the draft letter seems to date from 1939 as an accompanying list includes all the Méditerranée

works. In the event Scylla

was not shown. Another draft letter among the painter's papers, shows that it was very soon sent to New York with an exhibition of Surrealist paintings organised by the painter Gordon Onslow-Ford. Colquhoun had encountered him in Paris in the summer of 1939, when she met André Breton and Matta, and she seems to have visited his country house in the French Alps.37

The paintings that he gathered in London were dispatched in February 1940, perhaps partly as a precaution against wartime damage. Onslow-Ford himself followed to give lectures on Surrealism at the New York School for Social Research. Four months later, Colquhoun drafted a letter which indicates that her three paintings - Scylla, L'Helice (another Méditerranée

painting) and Cucumber

- were the only works not exhibited, provoking her to remark with some justification: 'It seems sheer waste, from everyone's point of view, since you don't consider me a Surrealist'.38 This inconsistency seems to reflect the internal crisis in British Surrealism in 1940, in the process of which Colquhoun was expelled by E.L.T. Mesens for not relinquishing her membership of other groups, chiefly secret occult societies. Herbert Read - another condemned for compromised allegiances - could soon agree that 'the Surrealist group, as you say, has disintegrated'.39 Colquhoun's three paintings remained in New York in storage arranged by Onslow-Ford into the following spring.40

She viewed the situation with enough seriousness to take legal advice from the Imperial Arts League about how to re-secure possession without jeopardising them in a wartime Atlantic crossing.41

On the American entry into the war in December 1941, Onslow-Ford moved to Mexico to avoid returning to his duties at the Admiralty and this may have further clouded the situation. It is not known when the paintings returned to Colquhoun, but Scylla

remained in her possession until purchased by the Tate Gallery.

Matthew Gale

October 1997

1

Colquhoun, letter to Tate Gallery, 9 June 1977, Tate Gallery catalogue files

2

James George Fraser, The Golden Bough, abridged ed., London 1929, p.670

3

Colquhoun Library, Tate Gallery Archive

4

Letter, 9 June 1977

5

Interview with the author, 16 June 1997

6

Tate Gallery Archive 929

7

Tate Gallery Archive 929

8

Repr. Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement, London 1985, p.91, pl.77

9

Letter, 9 June 1977

10

Interview, 16 June 1997

11

Dawn Ades, 'Notes on Two Women Surrealist Painters: Eileen Agar and Ithell Colquhoun', Oxford Art Journal, vol.3, no.1, April 1980, p.40

12

Ithell Colquhoun, 'Letters: Women in Art', Oxford Art Journal, vol.4, no.1, July 1981, p.65

13

Fiona Bradley, Surrealism, London 1997, p.51

14

Ades 1985, p.40

15

Repr. in col. Surrealism in England, 1936 and After, exh. cat., Herbert Read Gallery, Canterbury College of Art 1986, p.50, no.79

16

Photograph in the artist's records, Tate Gallery Archive 929

17

Repr. in col. The Surrealist Spirit in Britain, exh. cat., Whitford and Hughes, London 1988, no.14

18

William Johnstone, Points in Time: An Autobiography, London 1980, p.236

19

'The Volcano', London Bulletin, no.17, June 1939, p.15

20

Interview, 16 June 1997

21

Photograph in artist's records, Tate Gallery Archive 929

22

Repr. Chadwick 1985, p.125, fig.109

23

Ibid., p.128

24

Repr. Britain's Contribution to Surrealism in the 30s and 40s, exh. cat., Hamet Gallery, London 1971 [p.15]

25

Chadwick 1985, p.126

26

Ades 1980, p.40

27

Bradley 1997, p.51

28

Chadwick 1985, p.105

29

Tate Gallery conservation files

30

In conversation with Roy Perry, 6 July 1977, ibid.

31

'What do I need to Paint a Picture?', London Bulletin, no.17, 15 June 1939, p.13

32

Letter, 9 June 1977

33

Tate Gallery Archive 911.4.1

34

Letter, 9 June 1977

35

Notes from conversation with the artist, 10 Nov. 1977, Tate Gallery catalogue files

36

Tate Gallery Archive 929

37

Toni del Renzio interview, 16 June 1997

38

Draft letter, 10 June 1940, Tate Gallery Archive 929

39

Read, letter to Colquhoun, 26 June 1941, Tate Gallery Archive 929

40

Draft letter to Elizabeth Onslow-Ford, 27 Feb. 1941, Tate Gallery Archive 929

41

Letters to Imperial Arts League, 4 and 10 March 1941, Tate Gallery Archive 929

Film and audio

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- pun(53)

- countries and continents(17,390)

-

- Italy(4,473)

- classical myths: creatures(143)

-

- Scylla(5)

- sex and relationships(833)

-

- eroticism(409)

- sensuality(48)

- boat - non-specific(2,203)

You might like

-

Ithell Colquhoun Landscape with Antiquities (Lamorna)

1955 -

Ithell Colquhoun E.L.A.S.

1945 -

Ithell Colquhoun Attributes of the Moon

1947 -

Ithell Colquhoun Ages of Man

1944