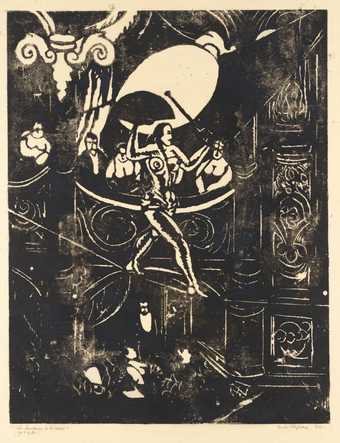

Fernand Léger

The Acrobat and his Partner

(1948)

Tate

Circus People

Artists have often been seen as outsiders to society. Many of them have also been drawn to other people and professions that haven’t fitted in with social rules. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the circus, carnival and travelling shows signalled a place of wildness, abandon, and escape. Many artists and others enjoyed the idea of freedom from the confines of laced up society. Of course the reality was often quite different.

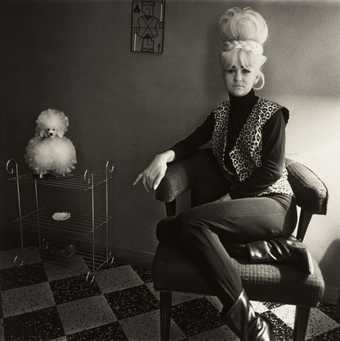

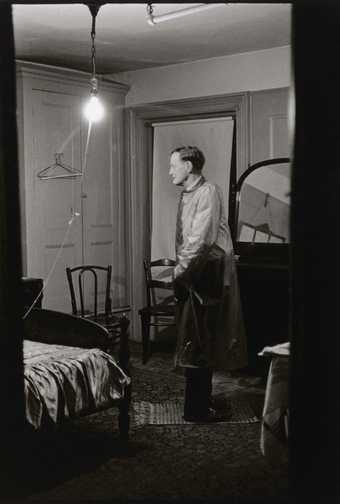

Diane Arbus

The backwards man in his hotel room, N.Y.C. 1961 1961, printed after 1971

ARTIST ROOMS Tate and National Galleries of Scotland

Diane Arbus photographed people she met on the streets of New York. She also made many portraits of people she came to know through the New York ‘freak shows’ (as they were called then). Her daughter said after her death, 'She was determined to reveal what others had been taught to turn their backs on.'

In this image from 1961 she photographed the contortionist Joe Allen, known as ‘The Backwards Man’ in a hotel room. From the waist up Allen faces to the left, while his feet and legs point in the opposite direction. He is wearing a shirt and tie and suit trousers, shined shoes and a see-through plastic rain mac, which both covers and draws attention to his body. Instead of photographing Allen at his show, Arbus takes his image in a domestic space. Lit by a bare lightbulb we see chairs, a dressing table and the corner of a bed. This familiar setting shows Allen as a person in their private space. At this time, performers like Allen could often experience cruelty and discrimination, and be stared at both on and off stage. Here, Arbus presents Allen, not as someone to be gawped at, but as a person and a performer living his life.

Travelling with the Circus

August Sander also photographed the people who worked and travelled with the circus. Before this time most photographs were posed portraits taken in a studio. Sander was an early pioneer of documentary photography. He abandoned his photographic studio and set out on his bicycle to document all the kinds of people who lived and worked in his native area of Germany. His work was banned by the Nazis in the 1930s, because his real life portraits did not fit with their ‘Aryan ideal’. Sander also shows these circus workers as real people, rather than exotic performers.

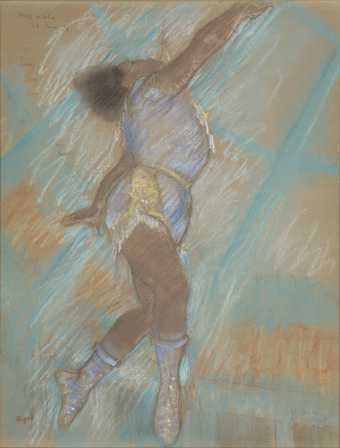

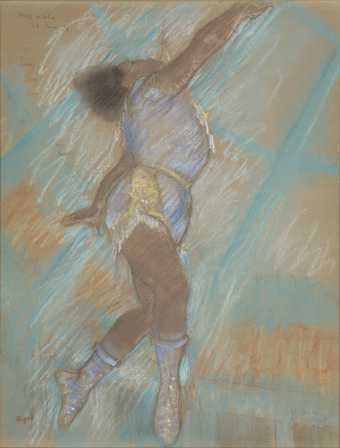

In the late 1800s artists began to paint the contemporary world around them. They turned away from painting classical subjects and myths and legends, and looked to the bustling cities instead. Edgar Degas was at the forefront of this movement in Paris. He was closely associated with the Impressionists.

Degas was fascinated by dancers and acrobats and the shows of the time. This work is a preparatory sketch for a painting. There are a number of similar sketches and he probably made them on the spot while watching Miss Lala being pulled up to the roof by her teeth.

Edgar Degas

Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando

(1879)

Tate

Circus scenes

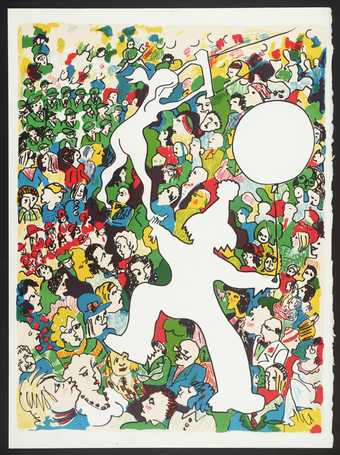

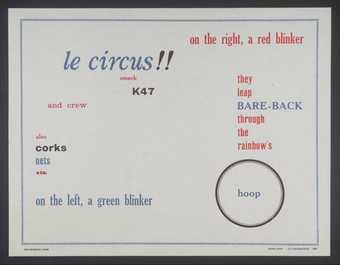

Many artists have been inspired by the lights, colours and excitement of the circus. Ian Hamilton Finlay’s poster poem artwork captures the sounds and movements of the circus ring as well as a painting or photograph.

Ian Hamilton Finlay

Poster Poem (Le Circus)

(1964)

Tate

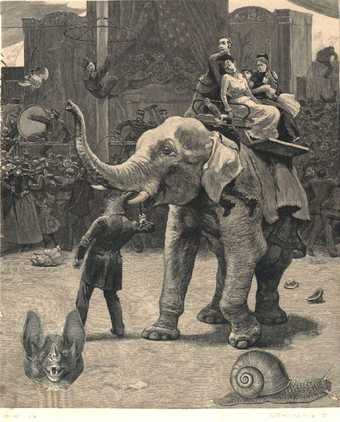

Circus animals

Until quite recently most circuses included wild animals that had been trained to do tricks. They were often kept in inhumane conditions and badly treated. Franz Roh’s Total Panic II shows a family’s ride on a circus elephant’s back going wrong. The scene of chaos comments on the panic of late-1930s Germany. In 2003 Douglas Gordon filmed the circus elephant Minnie performing tricks – particularly playing dead. Minnie was brought to New York from the Connecticut Circus. Gordon forces us to confront the cruelty of asking a wild animal to perform these actions. He implicates us in the cruelty as we watch it, as much as he is implicated by filming it.

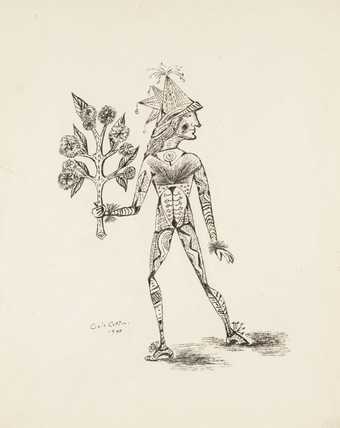

Clowns, harlequins and fools

The idea we have of the typical clown with the red nose and painted smile has its roots in many different traditions.

Harlequins and Pierrots were characters that came from the Italian commedia dell’arte, as did Punch from Punch and Judy. Popular from the 1600s, these travelling shows were current right up to the 1800s. They had acrobats or tumblers and also acted out comic and tragic tales. The traditional costumes of these characters – either the diamond patterned suit, or white robes with large black buttons or pompoms – still influence what we think of today as clowns.

The clown or the fool has played an important part in European stories and culture. Often, while we might be laughing at a clown, they are also pointing out the absurdity of life. Clowns in literature have often spoken the truth, but covered up or masked with jokes. The clown today has moved away from being a figure of innocent fun. Clown make-up and masks now have many darker undertones – maybe they are reclaiming some of the sinister properties a clown, jester or fool might have had in past years.

William Foster

A ?Clown in Mock Military Costume

(1811)

Tate

Walter Richard Sickert

Brighton Pierrots

(1915)

Tate

Mabel Nicholson

The Harlequin

(c.1910)

Tate

Max Beckmann

Carnival

(1920)

Tate

Kurt Schwitters

Untitled (The Clown)

(c.1945–7)

Tate

Cecil Collins

The Voice of the Fool

(1944)

Tate

Maggi Hambling

Max Wall and his Image

(1981)

Tate

© Maggi Hambling. All Rights Reserved 2020 / Bridgeman Images

Luc Tuymans

Illegitimate III

(1997)

Tate

Piccadilly Circus

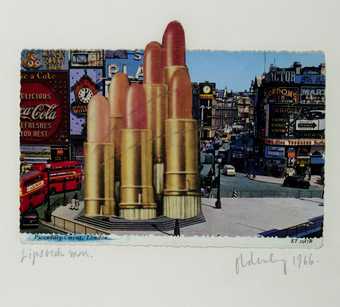

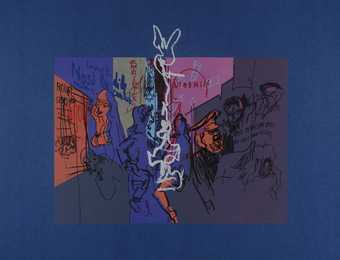

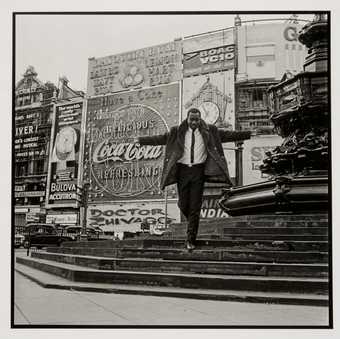

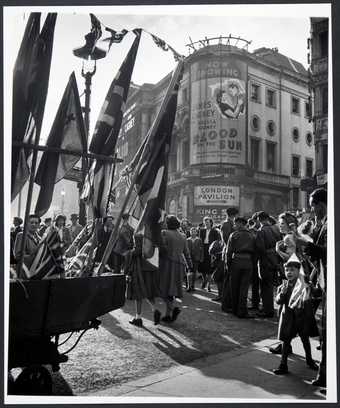

Circuses aren’t always clowns and acrobats. Some of the most famous British circuses are actually crossroads. Piccadilly Circus isn’t the only circus in London, but it is one that artists have returned to again and again. In the heart of Soho and London’s nightlife, it represents not only a literal crossroads, but a crossroads of culture. All walks of life have come through here, from flower sellers to bus drivers, actors to aristocrats. Sometimes real life is a circus.

Claes Oldenburg

Lipsticks in Piccadilly Circus, London

(1966)

Tate

Feliks Topolski

Piccadilly Circus

(1973)

Tate

James Barnor

Mike Eghan at Picadilly Circus, London

(1967, printed 2010)

Tate

Wolfgang Suschitzky

V.E. Day, Piccadilly, May 1945

(1945, printed 1998)

Tate

Dieter Roth

[title not known]

(1970)

Tate

Hannes Kilian

Piccadilly, London

(1955)

Tate

Jean Moral

Flowers in Piccadilly

(1934)

Tate

Have a go!

Sketch moving figures from life

Edgar Degas

Miss Lala at the Cirque Fernando

(1879)

Tate

Edgar Degas was inspired by the movement, colour and excitement of the circus. He made hundreds of sketches of dancers and acrobats, capturing their movements as well as the scene around them. But he didn’t convey movement only through the poses of the dancers. The quality of the marks he made on the page also expressed movement.

- Find a model. You want to draw from a real person – not photographs or videos. You could ask classmates or family members to sit (or stand) for you. Don’t worry about costumes etc at this stage, you’re just getting used to representing a figure.

- Set some time limits. Drawing classes often have a ‘warm up’ where you make lots of speed sketches. Try drawing a whole figure (even hands and feet) in 30 seconds, 2 minutes and 5 minutes. Fill a page with quick sketches so you can see them all together.

- Try different materials. How are your drawings different if you use a soft or hard pencil? What happens if you use a thick paint marker or an ink brush? Can you make more marks that describe the figure with oil pastels or chalks and charcoal? Don’t be afraid to make mistakes, there is no right and wrong with sketching – just things to try.

- Once you’ve had a go at still figures, try drawing figures in movement. Maybe you can find a dance or drama class that will let you sit in and sketch during rehearsals. Remember to focus on finding marks that describe the movement of the figures, and work fast!