In Tate Modern

Start Display

Free- Artist

- Virginia Chihota born 1983

- Original title

- Kuzvirwisa

- Medium

- Silkscreen print on paper

- Dimensions

- Frame: 1885 × 1385 × 50 mm

support: 1800 × 1300 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by Tate Americas Foundation, courtesy of Caro Macdonald in honour of the women of Zimbabwe 2017

- Reference

- P81969

Summary

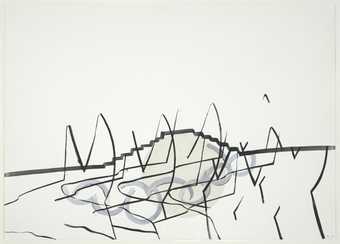

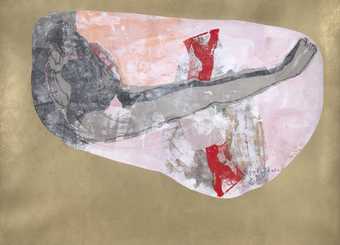

This is one of two screenprints in Tate’s collection by Virginia Chihota that share the same title and date; where this one is portrait format, the other (Tate T14806) is landscape format. Both prints are unique and therefore not editioned, and form part of an ongoing series of monoprints – five at the time of writing – with the collective title Fighting One’s Self (‘Kuzvirwisa’ in the artist’s native Shona language). The title and images communicate varying aesthetic approaches to the theme of mental and physical isolation. Though created in series, the works are considered individual and can be displayed as such. This particular print is notable for the aqueous application of typically viscous screenprinter’s ink, producing a watercolour-like effect. The cool palette is predominantly blue and purple, overlaid by thin washes of red. Only toward the left-hand margin can one discern filaments of the boldest red hue for which Chihota’s earlier works are known. Large concentric ovals of blue, purple and pale red form egg-like layers, within which a figure shields its face from view. The landscape-format work is dominated by luminous gold ink, suspended in the centre of which is a large sac-like form positioned along its horizontal axis. The ovoid shape contains a human figure whose small black face and torso recede in relation to the flexed arm and disproportionately elongated leg, both articulated in taupe. The warm pink tones surrounding the figure are accented by two small striated Y-shapes rendered in blood red, evoking a uterine environment. The composition of both prints bears strong allusions to fertility, the placement of the human figure within such a sac being intentionally womb-like.

Chihota’s work across drawing, painting and printmaking is deeply introspective, characterised by her use of symbols referring to female anatomy and foetal positions, rich colour and graphic forms to convey her perspective on personal experiences. In Fighting One’s Self she chose the Shona term for inner turmoil to address the fraught struggle to maintain a sense of self in the midst of change, a concern that she has described as the defining element of her practice: ‘My work is a reflection on the search for one’s self (and the perenniality of the self) in changing circumstances. Displacement creates uncertainty but the imperative to survive and the continuity one manages to maintain despite changing conditions inspires me.’ (Quoted in Kinsmann 2015, accessed September 2016.)

Chihota has drawn on recent changes in her circumstances, in particular becoming a wife and mother, and a temporary relocation to Tripoli in Libya with her family in 2012, followed by a turbulent period of displacement and relocation in the face of the escalating Libyan Crisis. While her choice of title foregrounds this personal tumult, her works have become increasingly abstract. They are rich in symbolic reference to fertility, loneliness and female subjectivities associated with traditional gender roles linked to pregnancy and the sequestration that can come with tending to very young children. Where figures do appear, they are places so as to convey nuances of dislocation, isolation and loneliness. The motif of the inverted body or head – as in Receiving Life (Kugamuchira Hupenyu) 2013 and Raising Your Own (Kurera Wako) 2014 – is one example. Another is the singular female figure placed within a block of colour or pattern that is surrounded by an expanse of blank space, as in the series The Root of the Flower We Do Not Know (Mudzi Weruva Ratisingazive) 2014. When multiple figures do appear in the same image, Chihota tends to signify disconnect by depicting them turned away from one another, or segregated into different quadrants, such as in The Prince of Life (Kuna Muvambi Wehupenyu) 2013 and the series Trust and Obey (Kuvimba Nekuterera) 2013.

Such concerns are also at the heart of works such as The Constant Search for Self (Kudzokorodza Kuzvitsvaga) 2013, also in Tate’s collection (Tate T14350). Separate, bulbous forms convey a sense of female loneliness or entrapment, while the gesture of obscuring them with washes of colour or densely applied marks further suggests loss of visibility, voice and agency. Ideas of nurture and safety associated with the womb seem antithetical to these concepts of being alone, yet it is precisely because of this that it holds especial significance to Chihota’s reading and representation of the universal quest for selfhood. Reflecting on the meaning behind her symbolic use of the womb in relation to the human condition, she has said that it is ‘an all-encompassing symbol for fertility, for a woman’s gift for gestation and the creation of life, a woman’s intuition and psychic abilities, and the subconscious … No one is excluded from being fruit of the womb and all that that encompasses. It yields to the human condition.’ (Ibid.)

Further reading

Portia Zvavahera et al., Dudziro: Interrogating the Visions of Religious Beliefs, exhibition catalogue, Zimbabwe Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 1 June–24 November 2013.

Houghton Kinsmann, ‘Depicting Thorns in Virginia Chihota’s Flesh’, AnotherAfrica.net, 28 January 2015, http://www.anotherafrica.net/art-culture/depicting-thorns-in-virginia-chihotas-flesh, accessed September 2016.

Emma Lewis and Zoe Whitley

June 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- isolation(290)

- texture(466)

- fertility(48)

- lifestyle and culture(10,247)

-

- cultural identity(7,943)

You might like

-

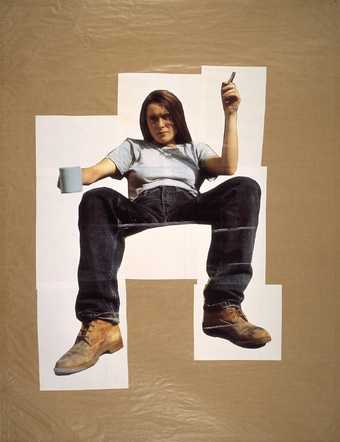

Sarah Lucas Self Portrait with Mug of Tea

1993 -

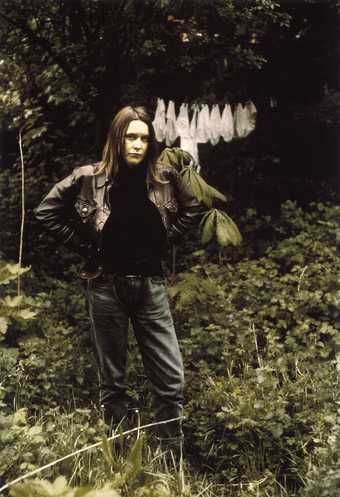

Sarah Lucas Self Portrait with Knickers

1994 -

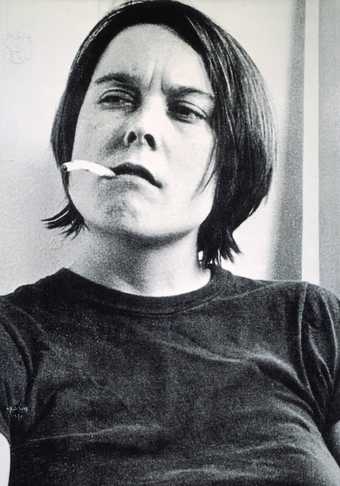

Sarah Lucas Fighting Fire with Fire

1996 -

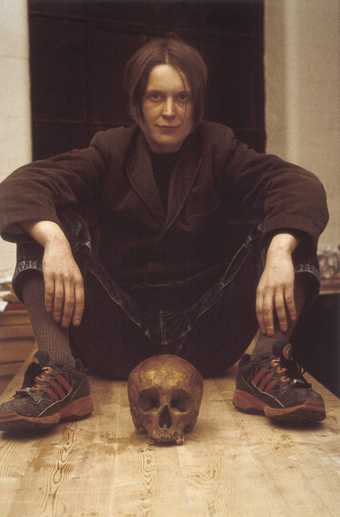

Sarah Lucas Self Portrait with Skull

1997 -

John Latham Ben N

2004 -

John Latham Presumed Level of Abstraction

2004 -

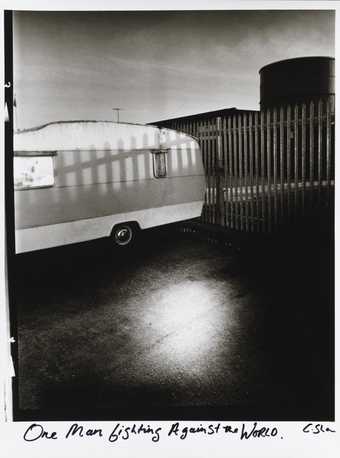

Chris Shaw One Man Fighting against the World

2007–12 -

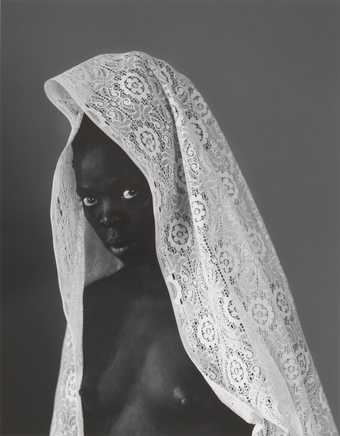

Zanele Muholi Thembeka I, New York, Upstate

2015 -

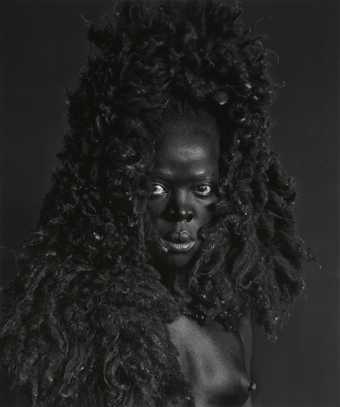

Zanele Muholi Somnyama IV, Oslo

2015 -

Alison Wilding OBE Migration Series 5

2005 -

Abraham Cruzvillegas AC: Blind Self Portrait: Glasgow-Cove Park

2008 -

Tracey Emin On her Side

2014 -

Virginia Chihota The Constant Search for Self

2013 -

Virginia Chihota Fighting One’s Self

2016