Not on display

- Artist

- Gillian Carnegie born 1971

- Medium

- Oil paint on fibreboard

- Dimensions

- Support: 749 × 584 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the Charities Advisory Trust 2007

- Reference

- T12486

Summary

Thirteen is a still life painting that represents a bunch of flowers informally arranged in a cut-down plastic bottle and set against a light neutral background. The plastic bottle and flower arrangement are tilted slightly forward at a skewed angle that projects them towards the viewer. The palette is dominated by earthy colours, with the still life motif and background sharing the same tonal range, which fuses them together. This is most evident in the white branches and leaves at the back of the bunch that seem almost to dissolve into the wall behind. Coming from the left, the light hits the back wall which gradates from bright white to a mixture of shades. The light is pale and flat, casting shadows only on the undersides of the leaves, and modelling the subject with slight gradations in tone. This treatment of light appears naturalistic, but at the same time is extremely stylised, diverting attention away from the painting’s subject to the way the image has been created. The combination of different stylistic approaches – a characteristic of Carnegie’s work – ranges from delicate touches and detailed drawing in the bunch of flowers, to thicker brush strokes and messy surfaces in the background, which is sketchier and more spontaneous in its execution.

Thirteen is one in an ongoing series of floral still lifes in which Carnegie explores pure painterly technique, its textures and aesthetic pleasures, through the representation of the same motif, a bunch of flowers in a cut-down plastic bottle. A genre traditionally deemed inferior when compared to history and religious paintings, portraiture and landscape, it was the French painter Edouard Manet (1832–83) who once referred to still life as the ‘touchstone of the painter’, asserting that an artist can say everything he has to say with ‘flowers, fruit and clouds’ (George Mauner, ‘The Last Flowers’, Edouard Manet: The Still-life Painting, exhibition catalogue, Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore 2001, p.144). Starting with Fleurs d’Huile 2001 (reproduced in Tufnell, p.50), followed by Black Flower 2002, Popol-vuh 2003 and Waltz I and II, both 2004, the works in this series are characterised by the simplicity of composition and precision of focus on the formal properties of the objects depicted. Despite the similarities that might be expected from the repeated representation of the same subject, the paintings in this series derive their individuality from variations in composition, size, format, lighting conditions, colour range, texture and style.

Working on different series as a painterly exercise, Carnegie explores the conventions of academic figurative painting and some of its genres such as still life, landscape, the nude and portraiture. It is significant that the source for her paintings are photographs that she has taken herself, and that the genres of painting she uses as motif do not include narrative or history painting. The rejection of all narrative, and the use of recognisable sources with familiar meanings attached to them, emphasise the artist’s interest in the nature of painting in and of itself. By highlighting the artificiality of representation, the artist reminds the viewers ‘of what has most obviously been forgotten during the process of looking ... [that they are looking at a painting] ... leaving themselves behind in one respect returning them where they actually are’ (quoted in ‘Paint it Black. A conversation between Gillian Carnegie and Simon Thompson’, press release, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York 2003, http://www.andrearosengallery.com/exhibitions/2003_2_gillian-carnegie, accessed 27 April 2009).

Behind Carnegie’s choice of subject matter, from the still lifes to the sober ‘black square’ series (see Black Square 2008, T12935), lies the artist’s obsession with the construction of images from paint. Her variations of texture and density, from heavy impasto to thin washes, emphasise the tactile nature of the medium, and draw attention to the tension between surface and illusion, between its physical facts and its figurative content. In this way, the image represented withdraws and the objectness of the canvas takes over.

Further reading:

Monika Szewczyk, ‘Her Pornographic Imagination’, Afterall, no. 16, Autumn–Winter 2007, pp.73–9.

Lizzie Carey-Thomas, ‘Gillian Carnegie’, Turner Prize 2005, exhibition brochure, Tate Britain, London 2005, [pp.6–7].

Polly Staple, ‘The Finishing Touch’, frieze, no. 64, January–February 2002, pp.72–5.

Carmen Juliá

April/May 2009

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

Thirteen is one of a series of floral still life paintings. In each, Carnegie paints a bunch of flowers in a cut-down plastic bottle. Still life is a traditional genre of art alongside history and religious painting, portraiture and landscape. Carnegie explores the conventions of these genres. Although not concerned with narrative, she uses recognisable sources, with familiar meanings attached to them. This emphasises her interest in the nature of painting itself. She wants to draw viewers’ attention to the fact they are looking at a physical painting.

Gallery label, December 2020

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- objects(23,571)

-

- vessels and containers(2,157)

You might like

-

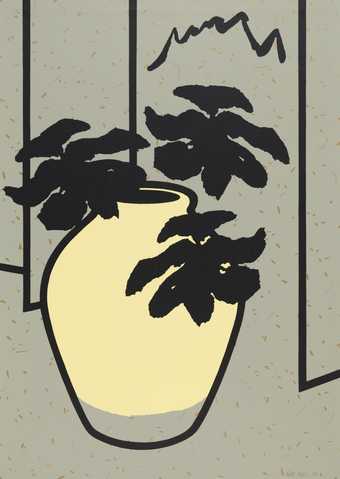

Alex Katz Ocean View

1992 -

Patrick Caulfield Cream Glazed Pot

1979 -

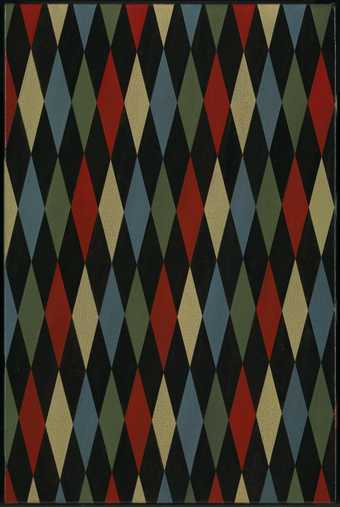

Gillian Carnegie Untitled 4

2004 -

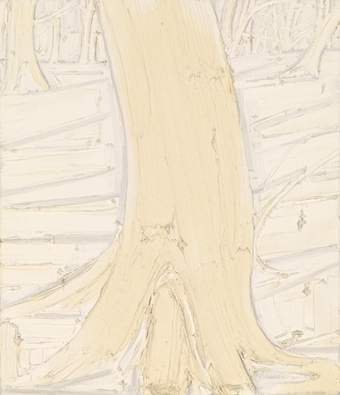

Gillian Carnegie White on White

2007 -

Gillian Carnegie Voi

2004 -

David Hockney White Porcelain

1985–6 -

John Murphy An Indefinable Odour of Flowers Forever Cut

1982–4 -

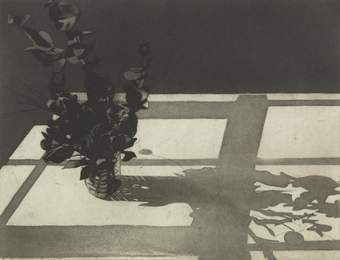

Thelma Hulbert Black Screen: Dried Leaves

1983 -

John Wonnacott Studio Conversation I

1993–4 -

Maggi Hambling Father, Late December 1997

1997 -

Gillian Carnegie rsXXII-/8-7

2007 -

Gillian Carnegie Black Square

2008 -

Gillian Carnegie Hanser

2010 -

Gillian Carnegie Untitled

2008 -

Maggi Hambling 2016

2016