In Tate Liverpool

Democracies

Free- Artist

- Chila Kumari Singh Burman MBE born 1957

- Medium

- Etching, lithograph and paint on paper

- Dimensions

- Unconfirmed: 612 × 812 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Tate Members 2014

- Reference

- T14091

Summary

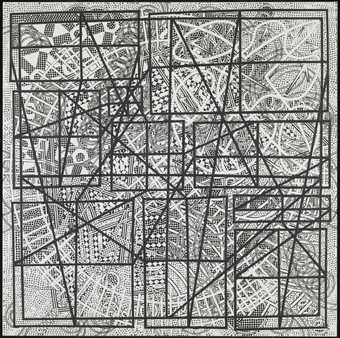

This is one of a group of six unique prints in Tate’s collection from Chila Kumari Burman’s Riot Series (Tate T14090–T14095), each of which is individually titled. They were made in 1981 and 1982 with the master printmaker Stanley Jones (born 1933) in the Printmaking Department at the Slade School of Fine Art in London, where Burman was a student at the time. The Printmaking Department had established a reputation for experimenting with a range of techniques and this can be seen in this series. After a variety of trials, Burman and Jones decided to work with a combination of processes in each print – etching and silkscreen, etching and aquatint or etching and lithograph. The tensions generated by the combination and overlaying of two material techniques embodied the violence embedded within the subject matter of the work, echoing the theme of conflict as well as affecting the final appearance of the prints. The historian Lynda Nead has written about Burman’s process of layering images:

Particular themes begin to emerge from Burman’s work from the 1970s and 1980s. Firstly, there is the idea of layering: of surfaces being built up, one upon another, creating dense walls of ink, paint, line and meaning. And secondly, there is the theme of fragmentation: of the image being broken up and subsequently reconstituted in order to shift stereotypes and to create radical forms of meaning.

(Nead 1995, p.28.)

These characteristics are evidenced in the prints of the Riot Series, as described below.

Triptych No Nukes 1982 (Tate T14090) is a triptych comprising three black and white monoprints, displayed side by side, depicting a group of riot police wearing gasmasks. A red pattern made up of the hazard symbol for nuclear weapons or radioactive material has been printed over the images, making reference to the title of the work. The three parts of the work embody three stages in the production of the image: the etching plate was placed in the acid for progressively longer periods so that the image was correspondingly eaten away and gradually disintegrated, becoming darker and harder to decipher. This deterioration across the three states of the image reflects the anti-nuclear sentiment behind the work.

If There is No Struggle, There is No Progress – Uprisings 1981 (Tate T14091) is a black, white and red monoprint that has various levels of imagery superimposed one on the other. The work was made in direct response to the uprisings which took place in various cities across England in the summer of 1981, partly as a result of social unrest in response to the politics of the Thatcher government. The words ‘Liverpool’ and ‘Chapeltown’ refer to some of the locations of the uprisings. The red background depicts a newspaper-like image which is printed over with black blotches of paint and a variety of slogans such as ‘?Justice no more Equal Right’ and ‘the unpleasant features of Imperialism’.

Cut – Foot – Pupil – Uprisings 1981 (Tate T14092) comprises two black and white images of a policeman. The image is overlaid with a red grid-based sewing pattern for cutting out a garment. The process followed was similar to that used for Triptych No Nukes, where the plate was placed in acid repeatedly as a means to manipulate and degrade the image, but also to embody physically the violence and destruction evoked by the subject matter. The image of riot police in gasmasks recurs throughout the series. In Three Mug Shots in a Row 1982 (Tate T14093) the recurring image of a policeman wearing a gasmask and riot gear is presented as a series of mug shots, taken from three different positions: facing the front, turning to the right and turning to the left with his hands up). In Red Riots on Indian Paper 1981 (Tate T14094) a ragged black line is formed diagonally by an image of a dense group of riot police in gas masks, set against a background of red and white which becomes pure red in the top and bottom thirds of the sheet.

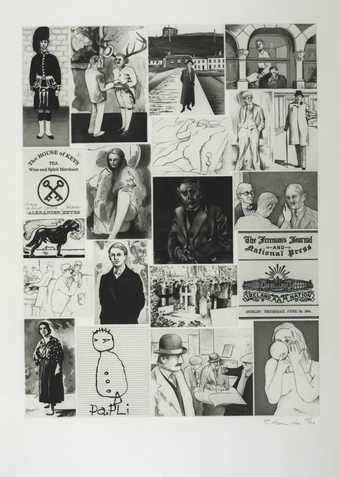

In contrast, Burman made Militant Women 1982 (Tate T14095) when she started to be involved in the production of the South Asian Feminist magazine, Mukti (1982–6). The print depicts a variety of black and white images of women referring to female road builders in India, executed female prisoners in England and females facing the Pass Law in Apartheid South Africa, whereby non-whites were forced to carry documents as a means of restricting their movement. This shift to a broader subject matter looks forward to Burman’s later work which has focused mostly on female identity within a global context. This includes a number of self-portraits which are aimed at breaking perceived stereotypes of Asian women. She has said:

My work is about reclaiming the image of Asian women, moving away from the object of the defining gaze, towards a position where I/Asian woman become the subject of display. My self-portraits construct a femininity that resists the racist stereotype of the passive, exotic Asian woman, imprisoned by male patriarchal culture. Rather I become the maker and definer of my own image.

(Quoted in ibid., p.61.)

Burman belongs to a generation of Black British artists whose families had settled in post-war Britain and who emerged onto the art world in the early 1980s. Alongside artists such as Lubaina Himid (born 1954), Eddie Chambers (born 1960) and Sonia Boyce (born 1962), her work raised issues around inclusion and visibility within the mainstream art establishment. Burman produced her most political works in the early 1980s, primarily as a reaction to riots and social unrest taking place around Britain at the time. She has often worked with innovative techniques, frequently combining processes and media such as photography and painting, photocopying and drawing within her works. She regards printmaking as fundamental to her practice for its non-hierarchical qualities, describing it as ‘democratic, versatile, colourful, creative, experimental, [a] drawing and photographic medium’ (quoted in ibid., p.28).

The Riot Series prints were exhibited for the first time in 1982 at Burman’s post-graduate show at the Slade. They were later shown in the Indian Artists UK Festival of India at the Barbican, London in 1983, The Thin Black Line, at the ICA, London in 1985, curated by Lubaina Himid, and at Liverpool’s Bluecoat Gallery in 1995.

Further reading

Lynda Nead, Chila Kumari Burman, Beyond Two Cultures, London 1995.

Leyla Fakhr

October 2013

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

Sir Terry Frost It is True

1989 -

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi 5. See Mom? A Baby’s Life is not all Sunshine

1972 -

Sir Eduardo Paolozzi 19. Electric Arms and Hands also Showing Love is Better than Ever

1972 -

Victor Pasmore What is the Object over There? Points of Contact No. 17

1973 -

Howard Hodgkin Artist and Model

1980 -

Richard Hamilton HOW A GREAT DAILY ORGAN IS TURNED OUT

1990 -

Terry Setch Once upon a Time there was Oil III, Panel I

1981–2 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There Was Oil (Raft)

1981 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There Was Oil (Beach)

1981 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There was Oil (Car on Beach II)

1981 -

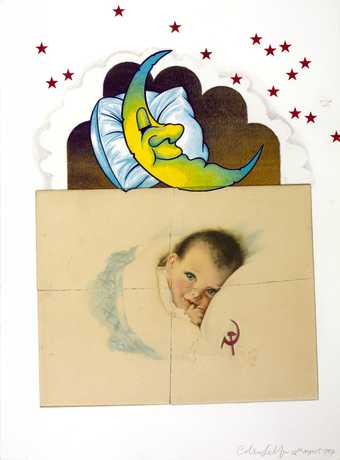

Colin Self Little Cuddly Baby Communist

1987 -

Bernard Cohen Out There

1994–5 -

Gillian Ayres RA CBE The Colour That Was There

1993 -

Chila Kumari Singh Burman MBE Triptych No Nukes

1982 -

Chila Kumari Singh Burman MBE Militant Women

1981