Claire Bishop

When we talk about participatory art today we often think of it as consensual and collaborative, but when you look back to the Futurist artists their notion of participation was designed to provoke, scandalise and agitate the public. You get a good sense of this in the printed material of the time, such as the Variety Theatre Manifesto of 1913. It included suggestions for disrupting the audience such as ‘spreading a powerful glue on some of the seats so that male of female spectators will stay glued down and make everyone laugh’; ‘selling the same ticket to ten people, traffic jam, bickering and wrangling’; ‘offering free tickets to gentlemen or ladies who are notoriously unbalanced, irritable or eccentric and likely to provoke uproars with obscene gestures, pinching women or other freakishness’; and ‘sprinkling the seats with dust to make people itch and sneeze’. Are these infantile provocations, or were they aligned with Futurism’s political agenda?

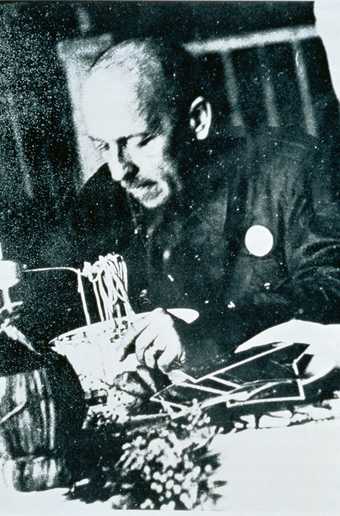

Filippo Tomaso Marinetti in Paris in the 1920s

Courtesy Conway Lloyd Morgan

Boris Groys

If you read the descriptions of the events that the Futurists organised, you notice that they always tried to antagonise with gestures, actions and speeches. One of their most famous declarations was ‘War, the World’s only Hygiene’. Such behaviour provoked anger and even disgust in the public, and aimed to destroy the long-held benign contemplative attitude of the spectator which had been the standard position of art audiences in the nineteenth century. The goal was to involve the audience in an event that was organised and ultimately controlled by the artist – even if this involvement took an adversarial form. Better to antagonise the audience than let it remain neutral.

Claire Bishop

I think it’s important that they’re using performance as a way to do that, and specifically using variety theatre as a model for the serate (the evening performances). First, the serate were characterised by non-sequential episodes of different types of performance, such as variety theatre or cabaret (theatrical events, poetry readings, manifesto readings, etc); secondly, variety theatre is a lower-class mode of entertainment, and has a greater degree of interaction than conventional bourgeois theatre. To quote Marinetti in the Variety Theatre Manifesto again: ‘The variety theatre is alone in seeking the audience’s collaboration. It doesn’t remain static like a stupid voyeur but joins noisily in the action, in the singing accompanying the orchestra, communicating with the actors in surprising actions and bizarre dialogues.’ Elsewhere, he talks about people smoking in the auditorium, as it creates a unifying ambience between the stage and the audience.

Boris Groys

At the beginning of the twentieth century people still maintained the tradition of a romantic understanding of art that was characteristic of the nineteenth century. The goal of art was to provoke deep emotions in the soul of the spectator – such as love and admiration. The viewer was supposed to be overwhelmed, especially if it was true, authentic art. However, at the end of the nineteenth century it became quite clear that people remained mostly completely neutral and unaffected by art. This was especially true of the new democratic audiences that were not trained to love it. So the Futurists tried to provoke again deep feelings in the audience – but feelings of hatred, resentment and disgust, rather than admiration and love. However, the goal remained the same romantic goal: to disturb the peace of the audience’s mind, to let it be overwhelmed by powerful emotions, albeit negative ones.

Claire Bishop

Marinetti is quite clear that mass audiences are not to be found through books, and he writes that 90 per cent of the Italian public go to the theatre. So there’s a deliberate choice of live performance as a mode of reaching people, which is then backed up by a media campaign, with press releases and reviews being sent out almost immediately after the event.

Boris Groys

And it is important to remember that the Futurists often presented themselves as clowns. They painted themselves in different colours, shouted unintelligible words, created ‘noise music’. In their own way, they were reviving the medieval tradition of Commedia dell’Arte. The Russian Futurists did the same, using the Russian medieval folkloristic tradition of lubok – a kind of comic strip. They also painted their faces, put big wooden spoons in their pockets instead of handkerchiefs and walked through the streets, frightening passers-by.

Claire Bishop

But did the Russian Futurists back this up with media attention as well?

Boris Groys

Absolutely. David Burliuk was especially good at that. He briefed the press before the events took place and organised the scandals. If the scandals didn’t take place, he created the illusion of them for the journalists.

Claire Bishop

But they were not allied to a political position in the way that the Italian Futurists were allied to an agenda of nationalism.

Boris Groys

Not at all. I wouldn’t say that Russian Futurism was completely free of nationalism, because it was informed and influenced by icon painting, primitive painting, folkloristic poetry and a celebration of Russian provincialism. The Futurists wanted to reveal very deep archaic, even archaeological, layers in the national culture. But they were neither militaristic nor state-orientated. Rather, there was a certain political affiliation between Russian Futurism and Russian anarchism. And the tradition of political anarchism was very strong in Russia.

Claire Bishop

One could talk about two phases of Italian Futurism: an early one up to about 1917, and after that when it is more aligned to fascism and the work becomes more mediocre.

Boris Groys

That’s true to an extent, but already by 1909 you see the first manifestation of all the fascist themes in Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto. You have this promise of a new, strong, modernised, industrialised Italy coming on to the European scene. It’s absolutely impossible to imagine any Russian Futurist poet or painter at that time praising the state, or wanting it to be mobilised and militarised.

Claire Bishop

But this is also partly a result of Italian art being dominated by such a strong historical tradition since the Renaissance – and wanting to escape from that tradition.

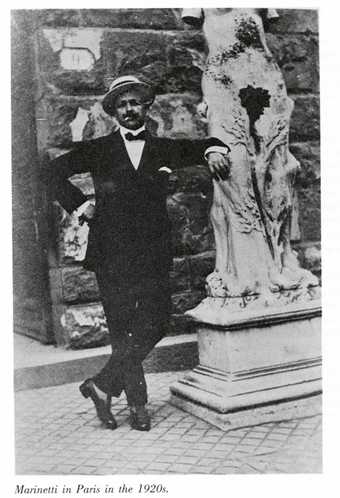

Poster for the tour around St Julien le Pauvre church in Paris led by André Breton and Tristan Tzara as part of the Dada season of 1921

Courtesy Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet

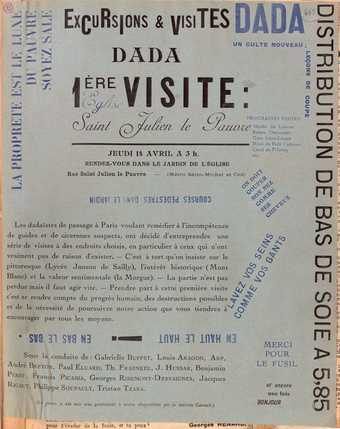

Tristan Tzara reading to the crowd at St Julien le Pauvre church, Paris (1921)

Courtesy Bibliothèque Littéraire Jacques Doucet

Boris Groys

Yes, there is no question about that. On the other hand, Russian art was as dominated by academicism and naturalism as any art of that time.

Claire Bishop

The three things that characterise Futurism for me are the politics, the provocation and the use of the media. It is rare to find these in equal measure in subsequent art.

Boris Groys

Futurism tried to create a total, even totalitarian, space – a space that one cannot escape. It is like the carnivalistic space that was later described by Mikhail Bakhtin. If you are a part of this, you cannot escape being beaten, being insulted, being pissed on, etc. You are pushed into the active position because there is no way out of it. As a spectator you find yourself having to defend yourself against the artist, and in doing so you become a part of the artwork. I think that was a real innovation – making the neutral, spectatorial position impossible, including the spectator by excluding the possibility of being outside.

Claire Bishop

That’s a very good way of putting it. I’m interested in how Italian Futurist performance then develops into Dada, because you can see the same patterns emerging in what took place at the Dada nightclub Cabaret Voltaire (founded by Hugo Ball), but without a defined political position; indeed, they refuse existing positions by embracing nihilism and meaninglessness. One (late) Dada event is worth mentioning in particular, since it breaks with the tradition of cabaret performance. In April 1921 André Breton, Tristan Tzara and others organised a tour around the church of St. Julien le Pauvre in Paris – or rather, around its churchyard, which at the time was used as a rubbish dump. In the flyer for the event they billed this as one of several planned tours that wished ‘to set right the incompetence of suspicious guides’ by leading ‘excursions and visits’ to places that have ‘no reason to exist’. Instead of drawing attention to picturesque sites, or places of historical interest or sentimental value, the aim was to make a nonsense of the social form of the guided tour. Like the Futurists, the Dada group also made good use of advertising and press releases to garner media attention (for example, one event in early 1920 had promised an appearance by Charlie Chaplin). A major difference from Futurism occurs when Breton comes to analyse this event (which he saw as a failure and as inducing collective depression): he no longer felt the need to scandalise the public. This becomes an important moment in the transition from Dada to Surrealism. Breton is now not interested in provocation, but in the construction of a moral position.

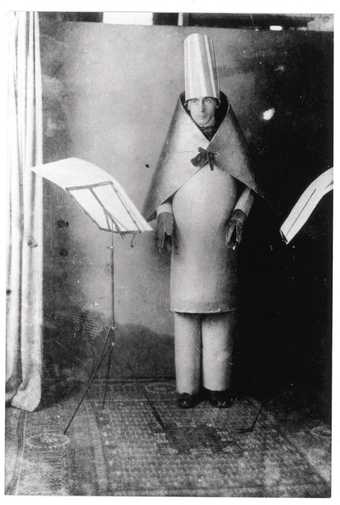

Hugo Ball reciting Karawane in a cubist costume at the Cabaret Voltaire, Zürich 1916

Gelatin silver on paper

Courtesy Fondation Arp

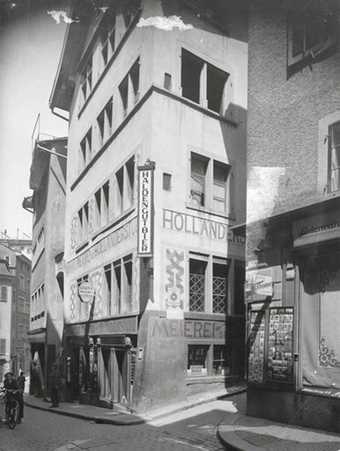

The site of Hugo Ball’s nightclub Cabaret Voltaire as photographed in 1935

Courtesy Baugeschichtliches Archiv Zürich

Boris Groys

Well, Dadaism was also akin to a certain kind of political anarchism. This is especially clear if one reads Hugo Ball’s Flight out of Time. After becoming increasingly disillusioned with political anarchism, he also leaves the Dada movement. But in any case there was a difference between Futurism and the Dadaist Cabaret Voltaire or Surrealism. Futurist activities mostly took place in open public spaces. With Cabaret Voltaire you bought tickets and would go willingly to participate, as was the case with those who experienced the tumultuous reaction to Dalí and Buñuel’s screening of Un Chien Andalou.

Claire Bishop

I can’t imagine there being a similar reaction today to a work of art. Maybe these reports of outrage in the face of avant-garde production in the 1920s are idealised. But maybe it is also the case that viewers would attend such events precisely for the pleasure of responding with outrage to provocation.

Boris Groys

There have been different sensibilities. If you read, for example, the diary entries of people from across the centuries about their experiences in front of art, what is interesting is that some were so impressed by a Raphael or a Leonardo da Vinci painting that they fainted, or would lose their appetite, or couldn’t sleep. In descriptions of the events at Cabaret Voltaire, there are many examples of people who fainted or needed medical help. Also in the Russian audience of the same time, some people almost lost consciousness when Mayakovsky allegedly said: ‘Pushkin should be thrown out from the ship of contemporaneity.’

Claire Bishop

Do you think there’s a connecting emotion? One is out of shock and the other out of pleasure?

Boris Groys

For a very long time people believed that there were certain religious, spiritual, moral and aesthetic values that lay at the basis of human civilisation, society, even everyday life. They thought that if these were put in question, attacked and lost, then the very basis of their existence would dissolve, everything would collapse and they just would not survive this general catastrophe. Today, nobody believes that ideal values build the fundament of our civilisation, so one can faint only at the news about a financial crisis. Earlier one believed that one could be killed by art – in a certain magical way. Then art overcomes a distance between the spectator and itself and reaches and penetrates the spectator somehow. At the beginning of the nineteenth century you were supposed to create something so beautiful that the spectator could not escape the spell of this beauty. Or something so terrible, so ugly and repulsive that he or she could not escape the shock. But I won’t say that the goal here is different. The goal is to create something that is so powerful that it undermines the capability of neutral, peaceful contemplation.

Claire Bishop

When looking at participatory art of later decades, such as the happenings, we can see that they are also coercive. For example, in some of Allan Kaprow’s happenings the script defined the action and everyone participated together, with no space for critical reflection. This is slightly different from the Situationists’ approach to collaborative events; some accounts exist that analyse and examine the dérive. The Situationist group, particularly as theorised by Guy Debord in the 1960s, wished to suppress art – but in order to realise it as life. We could see this as another way of eliminating a spectatorial position. It’s not about one group who do, and another group who watch or observe, contemplating the products of others. Throughout the 1960s we find different modes of participation taking place in art, all done in the name of various types of emancipation. With happenings in France, produced and theorised by Jean-Jacques Lebel, it is a sexual emancipation of the body; with Kaprow participation is figured more as a kind of existential awakening that would enable participants to have a more perceptive, responsive approach to the world.

Boris Groys

Well, everything is always about emancipation. The whole modern European culture is about emancipation. But I think the question is: emancipation from what? If you look at the late 1940s and 1950s, then it is emancipation from totalitarian space. Everything was about existentialism, about finding your true self and so on. Then suddenly in the 1960s one has a wave of a reprocessing of the totalitarian past and domestication of the totalitarian experience inside a stable framework of liberal democracies. Then it is understood as emancipation from individualism, from the isolation of the individual under the conditions of the Western bourgeois society.

Sol Goldberg's photograph of participants in Allan Kaprow's 'Women licking jam off a car,' from his happening 'household' (1964)

Courtesy Getty Research Institute

© Estate of Sol Goldberg

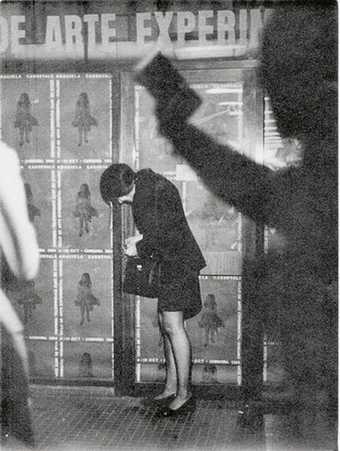

Graciela Carnevale

Cycle of Experimental Art 1968

Outside views of action, Rosario, Argentina

Photo: Carlos Militello

Courtesy the artist and Claire Bishop

© Graciela Carnevale

Inside and outside views of Graciela Carnevale's action as part of the Cycle of Experimental Art, Rosario, Argentina (1968)

Courtesy the artist and Claire Bishop © Graciela Carnevale. Photo: Carlos Militello

Claire Bishop

So what happens to provocational participation or even ‘domesticated’ participation (as you call it) under regimes other than liberal democracy? In the West, participation is invariably placed in opposition to a society of the spectacle. It is worth comparing it with participatory art in Latin America (under right-wing military dictatorships) and in eastern Europe and Russia (under communism). The examples from Argentina in particular, such as the performances produced by Oscar Masotta and Oscar Bony in Buenos Aires in 1966 and 1968, are quite violent and harbinger more recent work by, say, Santiago Sierra. We could also cite an action by Graciela Carnevale that seems to replicate modes of oppressive social experience that the dictatorship has put in place. Carnevale’s action, which took place at the end of the Cycle of Experimental Art in Rosario in 1968, involved locking the viewers in the gallery; she had covered the windows of the space with posters so that they couldn’t see out, and walked off with the key. It was then a question of waiting to see what would happen; how would the viewers release themselves from this situation? Carnevale was producing a moment of incarceration which had no clear outcome. Eventually, it was somebody on the outside who broke the window and allowed people to escape, rather than someone on the inside. When I’ve talked about this piece in public, some audiences have been horrified that an artist would do something this coercive in the context of a series of works of experimental art. In eastern Europe there’s a different mode again because of the specific relationship between public and private space and the fact that the work is produced in the context of communism.

Boris Groys

… which is a completely different context in which to make art.

Claire Bishop

The Moscow-based Collective Actions Group (active from 1976 onwards) is a good example of participatory art under communism. Performances usually involved taking a group of spectator-participants out of Moscow on a train for a few hours, to the remote countryside – often to snowy fields that were reminiscent of Malevich’s White Square paintings. There, some of the participants would be subjected to an enigmatic experience that subsequently became a focus of discussion and analysis by the group. These analyses are gathered together in an eight-volume publication called Trips to the Countryside, edited by the main theorist of the group, Andrei Monastyrsky. I know that you took part in a number of these events, such as The Appearance 1976, in which the participant spectators were asked to wait and watch for something to appear in a distant field. Monastyrsky then took a photo of you all watching, and later explained that you had all appeared for him. You argue that these kinds of events create a space of critical distance and spectatorship – in short, a space of liberal democracy – which did not exist under the conditions of communism. Under communism, everyone was a participant, and there was no ‘outside’ space for spectatorship and critical analysis.

Boris Groys

I think what should be very clearly said from the beginning is that communism is not a dictatorship. The concept of dictatorship presupposes the existence of a civil society which is independent of the state, which is something other than the state – and is suppressed by the state. In the Soviet Union nobody was suppressed, because everybody was always already a part of the state apparatus. Everybody worked for the state. The relationship between Soviet state and Soviet population was not a political relationship – not even a relationship of political suppression. It was a relationship between employer and employee. That is all. In the Soviet Union to be oppressed one has to create at first the possibility to be oppressed. One has to emancipate oneself to create a different space – outside of the totalitarian space – and then get oppressed. And that is what the participants of the Collective Actions Group did. In this sense the practice of this group is opposite to Western participation art. From Cabaret Voltaire to the happenings of the 1960s, artists tried to escape liberal democracy, individuation, aesthetic distance. It was a desire for totalitarian experience like the Romantic desire of the sublime. But in the case of participation art it is the experience of losing your individuality, dissolving your subjectivity in the ecstatic, Dionysian, totalitarian space – the experience of the political sublime. As Hugo Ball says: ‘To experience the demise of an individual voice in the general sonoric chaos.’ Going to these happenings was like going to the Swiss mountains in the nineteenth century. To experience totalitarian frisson, but under the secure conditions of the Western state. In Moscow at the time we were living this frisson all the time. So in this situation one rather tries to construct artificially the position of spectator that does not exist in the society as a whole.

Claire Bishop

So the Collective Actions Group was trying to construct distance and externality?

Boris Groys

To construct distance, construct spectatorship, construct the space of liberal democratic indecision – because the Soviet state was already a huge participatory installation. Inside this space we were trying to create an artificial space of liberal democracy based on the separation between artist and spectator by going to this kind of desert, white desert. So it’s space of nothingness. Not part of the state-occupied space. A private space, ultimately. However, it is clear that there is an intimate relationship between destruction and participative art. When a Futurist action destroys art in this traditional form, it also invites all the spectators to participate in this act of destruction, because it does not require any specific artistic skills. In this sense fascism is much more democratic than communism, of course. It is the only thing we can all participate in. So the Western participation art is a manifestation of nostalgia for an impossible dream of total destruction. And at the same time it is an act of total consumption, because the revolution of the 1960s was a revolution of consumption. Consumption is also an act of destruction. And what was a Soviet society? The Soviet society was a society of production without consumption. There was no spectator and no consumer. Everybody was involved in a productive process. So the role of Collective Actions and some other artists of the time was to create the possibility of consumption, the possibility of an external position from which one could enjoy communism. It was not a dissident position, not a position against the Soviet power. Only a very small group of dissidents were really against the Soviet power, but they actually didn’t know what to do.

Claire Bishop

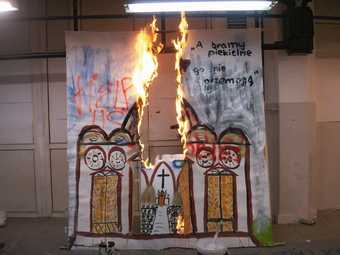

If we are talking about destruction and participation, then a recent work comes to mind, a video by the Polish artist Artur Zmijewski called Them 2007. It revolves around a series of painting workshops between four different ideological groups: the young Jews, the young socialists, Polish nationalists and the Catholic church. Each group produces a symbolic image of their beliefs; each image is then amended by the other groups. The only rule of the game is that everyone can interfere with, amend, adjust, or destroy anyone else’s image. Needless to say, it ends in complete conflagration, and the final shots show the studio full of smoke and the participants leaving the building. I think Zmijewski does actually want to achieve a progressive space of encounter, but he does this in a perverse way, by making the four groups confront each other. However, it is of course all stage managed – in the style of reality television – so he remains sovereign even though the events are not scripted and it is left open to people to play the game that he sets up.

Boris Groys

I think sovereignty is a really relevant word here because the artist-sovereign controls the territory on which this destruction takes place. We have the same thing in the French Revolution, we have the same thing with the Russian Revolution – Robespierre and Lenin controlling the space where the spontaneous collective destruction takes place.

Collective Actions Group's performance The Appearance in the countryside outside Moscow (1976)

Courtesy Boris Groys

Still from Artur Zmijewski's Them 2007

Courtesy Foksal Foundation © Artur Zmijewski

Oleg Kulik's performance Mad Dog or Last Taboo Guarded by Alone Cerber 1994

Courtesy Ikon Gallery © Oleg Kulik

Maurizio Cattelan

Southern Supplies FC 1991

Colour photograph, collage

77 x 100 cm

Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery

© Maurizio Cattelan

Claire Bishop

Yes. I find it hard to be able to identify what kind of authorship takes place in a work such as Zmijewski’s, where an artist sets up the rules of the game and watches it unfold, but without directing the action precisely, where the participants are given some agency. But then, of course, the artist’s editing is highly selective. All the footage of the action is recovered into a 30-minute film that has a clear narrative and point of view.

Boris Groys

Well, the artist as sovereign, as king, is not meant to do anything. He just symbolises and controls the place where everybody else does something. S/he authorises what these other people are doing. And is the ultimate author.

Claire Bishop

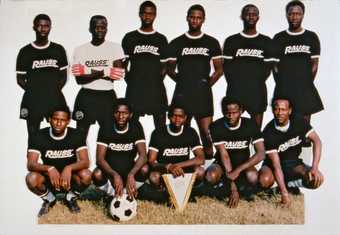

I think the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan is another person who is operating within the terms of Futurism today. He provokes and uses the media in a comparable way, although I believe he is lacking the political position that is so important to Futurism. One example is his work called Southern Supplies FC 1991. He put together a football team composed entirely of black immigrants and inserted them into a football league. They played matches, but ended up losing every game as they weren’t very good. More important than the collaborative aspect of the work, and the use of the real-time system of a football league, is the image that circulates of this all-black Italian football team. This is very ambiguous politically; on the one hand, it’s progressive (why not have an all-black football team?), on the other hand, the players are all wearing T-shirts emblazoned with the word Rauss (a play on raus, the German for ‘get out’). The word denotes a fictional sponsor, but also tells the uncomfortable truth of what many anti-immigration nationalists might think when seeing the picture. So it’s a troubling image that cannot be read clearly one way or another.

Boris Groys

We started by saying that the Futurists were extreme, but also very clownlike – and Cattelan fits into this scenario very well. The Futurists didn’t have any fear of looking laughable. And it was maybe a real emancipation, because contemporary art became very serious and so concerned with its public image. As well as Cattelan I would also include Oleg Kulik, whose early actions involve behaving like an aggressive dog, biting people and embarrassing them in the street – but being a clown-esque entertainer at the same time. That also reminds me very much of the Futurists.

Claire Bishop

Yes. But, again, I think the thing that’s lacking in all of these examples, which deal with provocation and media attention, is that none is aligned to an identifiable political position.

Boris Groys

That’s right. I think the connection here is only nostalgic. As I said, it’s kind of playing with totalitarian sublime, but with totalitarian sublime that is already not dangerous.

Claire Bishop

Was Futurism the first of the right-wing avant-gardes?

Boris Groys

Well, German Expressionism was partially affiliated to National Socialism in its early days.

Claire Bishop

It raises the question of which of the array of artistic positions we see around us today, globally, could be considered right-wing – and is the art market?

Boris Groys

Liberal democracy and market economy are not right-wing. I think we have to wait for that. Communism was from the beginning not unlike liberal democracy, because both of them are caring about the material wellbeing of people in the first place. That is why the war between them remained the Cold War. To create a true space of political participation one has to sacrifice his privacy – ultimately his life. But who is ready to sacrifice anything at all today? Well, we have that now in Islamic fundamentalism. But in Western culture the tradition of pure sacrifice is predominantly a right-wing fascist tradition – the only alternative to the liberal bio-politics that proclaim life to be of the highest value. In fact, we can see Futurism is a kind of artistic re-enactment of terrorism. There is a long tradition of Italian terrorism actually – from the nineteenth century – as there is a long tradition of Russian terrorism. So that’s two cultures where classic terrorism actually emerged, and also was conceptualised. So we can see Russian and Italian Futurism as a kind of nostalgic re-enactment of nineteenth-century terrorism… But against contemporary terrorism the artists have no chance in competition. The Futurists wanted to be like hurricane Katrina – not like a shelter against it. Their every work can be understood as non-constructive, non-objective, senseless. Today, artists complain that they have no practical impact on society, that their projects fail, that they cannot change the world. But, fundamentally, every work is senseless and every project fails. The only difference between artist and non-artist is that the non-artist can not make the failure of his/her project a part of the next project – and the artist can. Art is a wonderful place where you can reflect on the failure of utopia – repeating this failure time and again. It is something that is almost impossible outside of art.

Claire Bishop

Is it? I’m not sure.

Boris Groys

It is. It is impossible because, outside of art, failure has no value. If you fail, you just fail. But in art your failure becomes almost automatically an artistic achievement. At least you can always sell it as such.

Claire Bishop

Yes, I think that’s true. I’m just a little resistant to it, because it sounds too easy.

Boris Groys

Yeah, but it also applies to Futurism, because all their actions failed. Neither did they create a new Italy, nor did they create a modern lifestyle…

Claire Bishop

But they gave momentum to a political project which did achieve changes and which did modernise…

Boris Groys

And what happened? Mussolini came to power. And what happened after that? Mussolini failed. And now we don’t like Mussolini, but we love Futurism because Futurism was not only a part of the fascist movement, it was also an aesthetic anticipation of the failure of the fascist movement. Futurism already reflected on the clown-esque, the absurdity and senselessness of the fascist action. It already prefigured and reflected on its kitsch aspects and complete ineffectiveness in real life. In this sense, I would say that Futurism created the aesthetics of fascism. At the same time it has shown the impossibility of this aesthetic and anticipated its failure – and that’s why we now can love Futurism even if we cannot love fascism.