In Tate Britain

Prints and Drawings Room

View by appointment- Artist

- Brassaï 1899–1984

- Original title

- Femme au Monocle

- Medium

- Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper

- Dimensions

- Unconfirmed: 290 × 210 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Accepted by HM Government in lieu of inheritance tax from the Estate of Barbara Lloyd and allocated to Tate 2009

- Reference

- P13108

Summary

Young Lesbian at Monocle 1932 is a medium-size black and white photograph by the Hungarian photographer Brassaï that depicts a woman sitting at a table in a bar or restaurant. Her surroundings suggest opulence: the table is covered with a white tablecloth and on this are placed two silver-rimmed plates and an ornate silver ice bucket bearing the branding of the high-class French champagne company George Goulet, inside which is a bottle produced by another prestigious champagne maker, Lanson Brut. The woman holds a near-empty glass to her lips with her left hand, while in the other is a cigarette. She wears smart, masculine-looking clothes – a suit, a cravat and a large gold ring – that reflect her elegant surroundings, and her hair is waxed down with pomade, accentuating her masculine appearance. The woman sits on a bench that runs behind the table, and the chair opposite her, visible in the lower right foreground of the scene, is unoccupied. The presence of the empty chair, as well as the melancholy expression on the woman’s face as she gazes towards the right side of the frame, seem to emphasise the subject’s solitude. The photographed scene has a large white margin around it that has been signed in the bottom right corner by the artist, while the bottom left bears an inscription indicating that this print is number nine in an edition of forty.

This photograph was taken in Paris in 1932. During 1931 and 1932 Brassaï frequently walked around the city at night carrying his camera, tripod, magnesium flash powder and a box containing twenty-four glass plate negatives (the most he could carry) in order to photograph Parisian nightlife. As the work’s title suggests, Young Lesbian at Monocle was taken during Brassaï’s visit to Le Monocle, a lesbian nightclub in Montmartre. Brassaï befriended a regular attendee of the club named Claude and accompanied her there one night in 1932. After talking to his chosen subjects and asking for permission to photograph them, he set up his camera and tripod, and when some time had passed and his subjects had begun to relax, Brassaï took a small number of photographs of them. He then developed the glass negatives in the kitchen of his Paris apartment, which he used as his darkroom at the time, and printed them at a later date. (See Hutchins 2007, p.192; Anne Wilkes Tucker, ‘Notes on Brassaï’s Photographic Technique’, in Wilkes Tucker, Brassaï: The Eye of Paris, exhibition catalogue, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 1997, pp.157–8.)

Brassaï wrote in 1976 that his decision to photograph Parisian nightlife emerged from his conviction that ‘this underground world represented Paris … at its most alive, its most authentic’ (Brassaï 1976, p.3). In order to ensure his images’ authenticity, Brassaï infiltrated the Parisian venues and social groups he was interested in portraying, becoming a regular presence within them before he introduced the idea of photographing them. However, with his photographs taken at Le Monocle, Brassaï – a heterosexual male – could not blend into the scene as he usually would, and his process of engaging with his sitters in this case was therefore necessarily less subtle (see Hutchins 2007, p.192). The historian Frances E. Hutchins has argued that this resulted in an uncharacteristic distance between Brassaï and his sitters in the Monocle photographs, stating that

in some cases, this masquerade would have been more believable, but at the Monocle, there is no chance that Brassai will be mistaken for ‘une amie’. At Le Monocle and [the gay nightlclub] the bal musette, the contradiction inherent in Brassai’s belief in photography as a truth recording mechanism, coupled with his willingness to construct seemingly candid scenarios, comes to the fore.

(Hutchins 2007, p.192.)

Furthermore, Hutchins has argued that this distance between the subject and sitter results in the presentation of the lesbian as ‘other’, such that Brassaï ‘perpetrated the trope of queer exoticism’ (Hutchins 2007, p.191).

Brassaï took Young Lesbian at Monocle as part of his project Paris by Night, much of which was published as a book of the same name in 1933 to wide critical acclaim. Although this image was photographed for the Paris by Night series, Brassaï first printed and published it in 1976 in his book The Secret Paris of the 30s, and the photograph is one of a number of images of gay and lesbian nightlife that Brassaï published for the first time that year.

Further reading

Brassaï, The Secret Paris of the 30s, trans. by Richard Miller, London 1976, pp.147–65, reproduced p.150.

Annick Lionel-Marie and Alain Sayag, Brassaï: ‘No Ordinary Eyes’, exhibition catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London 2001, reproduced p.88.

Frances E. Hutchins, ‘The Pleasures of Discovery: Representations of Queer Space by Brassaï and Colette’, in Renate Günther and Wendy Michallat (eds.), Lesbian Inscriptions in Francophone Society and Culture, Durham 2007, pp.189–203.

Michal Goldschmidt

November 2014

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- places of entertainment(399)

-

- club(28)

- eating and drinking(409)

-

- drinking(267)

- smoking(280)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

- drink, wine(58)

- table(754)

- table cloth(51)

- plate(122)

- wine cooler(3)

- bottle(289)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- sitting(3,347)

- woman(9,110)

- France(3,508)

- sex and relationships(833)

-

- lesbianism(262)

- transvestism(29)

You might like

-

Brassaï Chartres Cathedral in Winter

1946, printed later -

Brassaï The Urchin Bijou, Bar de la Lune

1932, printed 1960–9 -

Wolfgang Suschitzky Lyons Corner House, Tottenham Court Road, London

1934, later print -

Iwao Yamawaki Cafeteria after lunch, Bauhaus, Dessau

1930–2, printed later -

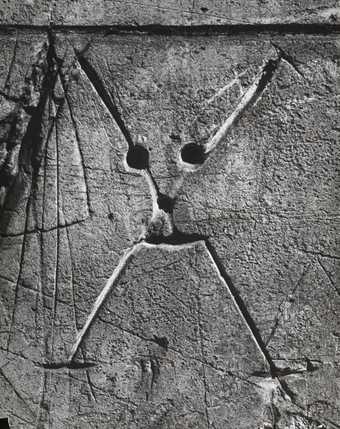

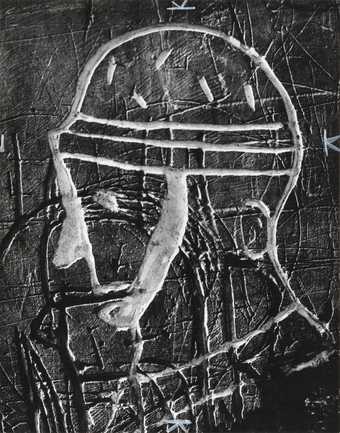

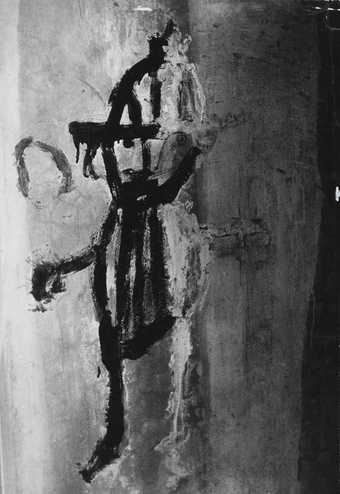

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s -

Brassaï Graffiti

c.1950s