Not on display

- Artist

- Sonia Boyce OBE born 1962

- Medium

- Watercolour, pastel and crayon on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 1238 × 1830 mm

frame: 1290 × 1878 × 70 mm - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1987

- Reference

- T05020

Display caption

Missionary Position II draws inspiration from the intersection of different cultures. Boyce uses herself as the model for both figures, reflecting her growing antipathy towards her Christian upbringing. The praying figure suggests passive acceptance while the figure on the right proposes an alternative position. The head-wrap, adopted in Britain and the Caribbean in the 1970s, is inspired by Rastafari and reflects a growing sense of cultural freedom and connectedness across the African diaspora. By contrast, the ‘missionary position’ title stands as a metaphor for the role of Christian missionaries in imposing colonial rule and oppression.

Gallery label, January 2022

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Sonia Boyce born 1962

T05020 Missionary Position II 1985

Watercolour, pastel and conté crayon on machine-made wove paper 1238 x 1830 (48 3/4 x 72)

Purchased from Gimpel Fils (Grant-in-Aid) 1987

Inscribed ‘Missionary Positions II position changing' top centre, ‘Laard but look my trials nuh - they say keep politics out of religion | and religion out of politics | but when were they ever seperate? [sic] Laard give me strength' along bottom, and ‘S Boyce | 1985 c' upside down on back b.l.

Exh: From Two Worlds, Whitechapel Art Gallery, July-Sept. 1986 (no number, repr. p.29)

Sonia Boyce, Air Gallery, Dec. 1986-Jan. 1987 (no number, repr. [p.5])

The Essential Black Art, Chisenhale Gallery, Feb.-Mar. 1988 (no number, repr. p.32)

Approaches to Realism, Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool, April-May 1990, Art Gallery, Oldham, June-Aug. 1990, Goldsmiths' Gallery, Jan.-Feb. 1991 (no number, repr. p.11)

Lit Michael Archer, ‘Sonia Boyce: Air Gallery', Art Forum, vol.25, no.7, March 1987, p.144, repr. p.143

John Roberts, ‘Interview with Sonia Boyce', Third Text, no.1, Autumn 1987, pp.62-3, repr. p.63

‘Black Women's Visual Art', Spare Rib, no.188, March 1988, p.12, repr. p.9, col. detail on front cover

Tate Gallery Report 1986-88, 1988, p.84, repr. (col.)

Gilane Tawadros, ‘Beyond the Boundary: The Work of Three Black Women Artists in Britain', Third Text, nos.8/9, Autumn/Winter 1989, p.142, repr. p.143

‘Missionary Position II' depicts two female figures in a domestic interior in front of a sofa. One kneels in prayer with eyes closed. The other half-reclines, stretching out her right arm towards the face of her companion. Positioned between them at the top edge of the picture is a blue crucifix. Above the heads of the women, who are dressed in brightly coloured clothes, are two ornamental birds, cropped by the top edge of the picture. To the left is a table lamp with a bust of a Black girl as its base. The patterns of the warm pink wallpaper and of the orange paisley carpet enhance the artist's decorative use of high-keyed colour in this work.

T05020 was made between January and February 1985 in Plaistow, London, where Boyce was living with her parents. It took approximately two weeks to execute, although the time spent in preparation for the work was much longer. The image was conceived more or less completely before its execution. In preparation she made separate sketches, no more than 10 x 10 cm in size, of each figure and the various elements that make up the composition. These were then projected onto a sheet of paper fixed to the wall by means of an epidiascope, which functions like an overhead projector. The figures were traced onto the sheet first and the rest of the composition was organised around them. Boyce has drawn the figure from life since fifteen years of age. In conversation with the compiler on 4 January 1992 she commented that the process of enlargement, however, sometimes reveals inaccuracies in her drawing. She noticed, for example, that the outstretched arm of the figure on the right looks broken. Nevertheless, she felt that this awkwardness added to the tension between the three-dimensionality and the flatness of the image, which was part of her intention. Before working in pastel Boyce gave the paper a watercolour wash of red, purple or orange in order to achieve the dark rich tones she desired. The watercolour provided a base for the effective depiction of dark skin colour.

Boyce was born in Islington, London of Caribbean parents, her mother from Barbados, her father from Guyana. She belongs to a generation of ’Black artists’, who emerged in the early 1980s. Her peers included Eddie Chambers (born 1960) and Keith Piper (born 1960) who aimed to establish a visibly ‘Black art' that addressed social and political issues relevant to ethnic groups in Britain.

‘Missionary Position II' is one of a group of large, brightly coloured, figurative pastel drawings exhibited by Boyce at the Air Gallery in December 1986. Critics interpreted the works as autobiographical narratives depicting the personal experiences of a young Black woman growing up in a white dominated society. In conversation with the compiler Boyce said that the main themes of the works were ‘identity' and ‘power relationships', themes which sprang from personal experience. However, she felt that some critics' responses had oversimplified the possible meanings of her pictures. She wanted her works to instigate discussion of the issues they addressed. In an interview given in 1987 she said:

African culture has a strong oral tradition; and in this sense I'm trying to be an oral translator through pictures. I gather things up which I remember, as a means of going forward to make certain cultural and political points. I'm making visible the warmth, as well as the confrontation of our daily lives as the basis upon which things can be discussed. (Roberts 1987, p.64)

For Boyce, the making of ‘Missionary Position II' was about trying to analyse a set of problematic and uncomfortable feelings relating to the Black person's experience of Christianity and the young person's reaction to authority.

The large drawings shown at the Air Gallery were the culmination of Boyce's efforts to visualise certain experiences that she had never seen depicted. When attending a foundation course at East Ham College of Art (1979-80) she was impressed by the work of visiting lecturer Margaret Harrison, artist and former lecturer at the College, precisely because it dealt with subjects that Boyce had not seen represented before. She wrote of Harrison, ‘She taught us that even rape can be a subject for our canvases - sexual abuse, abuse of trust, abuse of power, an everyday occurrence, a highly political act' (Air Gallery exh. cat., 1986, [p.8]).

While at East Ham, Boyce became aware of the works of American born painter Mary Cassatt (1844- 1926). She admired Cassatt's use of pastels and her contribution, as part of the Impressionist movement, to the development of a modern idiom. Through her reading of feminist histories of art, increasingly available in the early 1980s, Boyce learnt of the historical and political significance of the medium of pastel for women artists. She understood that the virtual exclusion of female artists from academies of art, and thereby from the means of mastering oil painting, meant that they had taken up other media such as pastel. Women were denied access to the life class and were, therefore, less able to produce grand history paintings that required accurate depiction of the human body. By adopting the medium of pastel Boyce was consciously referring to a specific aspect of the history of women artists in the Western tradition of art. Her decision to produce figurative pastel works on a large scale was partly a comment on the traditional expectations of both women artists and the traditionally less important medium of pastel. When asked by the compiler about the size of her works she replied:

I actually like doing large scale work. When I say large scale, I mean large scale for pastels, which is why people often think that they are paintings. It's not particularly large for painting but it is for pastel. I mean, you're talking about a millimetre at a time: it's a large area and it's very tedious, a very tedious method. But I liked the prospect that people would be confused.

In the making of such recent works as ‘From Tarzan to Rambo...' (T05021), Boyce was even more conscious of the scale of her work as a means of influencing audience response.

During the early 1980s Boyce was also profoundly influenced by the Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907-54). She saw a retrospective exhibition of Kahlo's paintings at the Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1982 and was immediately struck by the work. Kahlo's art is figurative and often naive in style, like traditional Mexican art. Although her paintings focus on her personal trials and sufferings, Kahlo also brought to her work an awareness of the cultural and political effects of colonialism in her native country.

Boyce's admiration for Kahlo was partly stimulated by her interest in feminist discussions and activities in 1979-80. At that time Boyce was particularly affected by the feminist dictum ‘the personal is political'. This pointed to the political implications of apparently natural modes of behaviour in which women are held to operate ‘naturally' in the domestic sphere whereas men ‘naturally' occupy the world of culture and business. In conversation with the compiler Boyce commented:

I was a teenager but it just spoke very deeply to me, ‘the personal is political', and so yes, that's why I have held on to Frida Kahlo because she embodied that meaning in her work. Seeing her work led me to doing what I did, because up until that point I didn't actually have a very strong direction. I had ideas, but I didn't have a direction in terms of developing visually.

The pictures in the Air Gallery exhibition seem to chronicle Boyce's experiences from childhood to adolescence (see, for example, ‘Big Womens' Talk', 1984, repr.The Other Story, exh. cat., Hayward Gallery 1989, p.102, and ‘Mr.-Close-Friend-of-the-Family Pays a Visit Whilst Everyone Else Is Out', 1985, repr. Air Gallery exh. cat., 1986, [p.8]), thus revealing a commitment to ‘the personal' as a valid subject. In ‘Missionary Position II', as in most of these works, Boyce used herself as a model for the figures. She has commented about her own size and colour in relation to her work:

Later, on the degree course, the tutors were dismissive. I was Black, therefore I wasn't there. I drew my feet very big on a patterned background. ‘I'm here, you can't wish me away'. Being a Black woman is a perpetual struggle to be heard and appreciated as a human being ... My life was shaken by the foundation course. I started doing self-portraits. I needed to see myself. (Air Gallery exh. cat., 1986, [p.6])

Boyce insists that, ‘Even though the images were of myself they weren't. It was only for expediency that they were really'. She prefers to interpret her self-portraits and the everyday objects included in her pictures as containers for ideas, as symbols as much as descriptions.

‘Missionary Position II' was the second and final work in what the artist originally intended to be a series of five works, the first being ‘Missionary Position I' (repr.Arts Review, vol.39, 16 Jan. 1987, p.12). In this series Boyce hoped to address a number of conflicting situations and ideas centering on her experience of religion within her own community, and in relation to British society as a whole. She has said, ‘I was trying to sort out for myself why I had particular antagonism towards religion in general and Christianity in particular'. Her family were, and still are, practising Christians of different denominations including Pentecostal, Methodist and Jehovah's Witness. She wanted to try to establish why it was that they did not share the aversion she and a number of her Black friends at college felt towards the Christian faith. Although she did not produce a five-part series as intended, Boyce feels that her original idea was realised, to a certain extent, through other works made during the mid-1980s that dealt with such issues as the influence of social institutions, home and school, the problem of authority, and the power relationship between parent and child.

The title of T05020 was chosen to suggest implicit rather than explicit meanings for the work. The term ‘missionary position' was used among English-speaking peoples of the South Sea Islands during the late nineteenth century to describe the position of sexual intercourse in which a man lies on top of a woman. The allusion to missionaries is thought to relate to the strict codes of sexual propriety introduced by Catholic missionaries in Polynesia in the nineteenth century. Certainly, the missionaries were appalled by the extent of nudity and apparent promiscuity. They insisted on segregating the sexes and imposing full European dress, which proved deleterious to the mental and physical health of the indigenous peoples. For Boyce, the ‘missionary position' stands as a metaphor for the submission of Black society to white society. This idea is also pursued in a later work, ‘Lay Back, Keep Quiet and Think About What Made Britain So Great', 1986 (repr. Hayward Gallery exh. cat., 1989, p.101). The title refers to the colloquial expression ‘Lay back and think of England', which exhorted women to submit dutifully to their husbands' sexual advances in order to produce children for the nation.

T05020 specifically addresses the issue of power relationships. In conversation Boyce has said, ‘central to all the work that I do is the issue of power relationships in terms of gender, in terms of age, in terms of race, in terms of class. It's about all those things overlapping in a way and for me, at that time, that was what Christianity signified'.

Boyce's antipathy towards Christianity stems from her belief that it enabled imperialism to take hold in Africa. In the mid-1980s she read a number of books which examined how missionaries provided a framework for white hegemony by establishing economic, social and cultural control in certain rural areas. The artist Eddie Chambers has also explored the history and effects of Christian missionaries in his installation ‘The Slaughter of Another Golden Calf', 1985 (Grapevine Arts Centre, Dublin, not repr.). Boyce had not specifically discussed the subject with Chambers but feels that it was very topical at the time owing to increased awareness of Black history and Black issues.

The term ‘Black art' was first used in the 1960s and 1970s to describe work that addressed the political conditions of Black people. It gained currency in the early 1980s through the efforts of a number of young Black artists, particularly Eddie Chambers and Keith Piper, who advanced the notion of ‘Black art' through such exhibitions as ‘Black Art an done' (Wolverhampton Art Gallery, June 1981) and who, in 1982, formed a radical ‘Black art' group, ‘The Pan-Afrikan Connection'. The latter was specifically concerned to establish the idea of a Black culture and to combat racism.

In T05020 the two young women are separated by a cross on the wall. This was not derived from an actual object but invented by Boyce to form a central pivot in her composition. The inscription on the left hand side of the cross, ‘Missionary Positions', appears associated with the praying figure. On the right is written ‘II position changing', which suggests that the semi-reclining figure on the right is in some way reacting against the oppressive influence of the Christian mission. This idea is also pursued in ‘Lay Back, Keep Quiet and Think About What Made Britain So Great', 1986. Three of the four panels that make up this piece refer to Britain's colonies in Africa, India and Australia: they bear the words ‘Mission', ‘Missionary' and ‘Missionary Position', respectively. The fourth panel comprises a self- portrait of the artist accompanied by the word ‘Changing'. Boyce's inscription at the bottom of T05020 encourages the reader to consider the political nature of religion:

Laard but look my trials nuh - | they say keep politics out of religion | and religion out of politics | but when were they ever seperate? [sic] Laard give me strength

Her use of vernacular Black language emphasises the cultural roots of Black Christians and is intended to convey a sense of the history of the Christianisation of Africa.

Boyce intended to suggest her ambiguity towards her family's Christian beliefs through the placement of the two figures. The one on the left prays with eyes closed, ignoring the other, whose arm stretches out towards her. Similarly, although the second figure seems to want to communicate with the young woman in prayer, her ear has been left unfinished by the artist, scrubbed out, suggesting that despite her efforts she cannot or will not hear. In conversation with the compiler Boyce said that she wished to imply a failure of communication between the two protagonists, hoping that this would give a sense of the frustration and confusion she had felt as a result of her Christian upbringing. At the same time, she wanted to suggest a lack of discussion about religious beliefs in general.

The title of the work, with its reference to patriarchal dominance, together with the androgynous appearance of the praying figure, has prompted several critics to identify the figure as male (see, for example, Tawadros 1989, p.142). However, the artist used herself as the model for both figures and thought of them as representing one person. The praying figure wears imagined ordinary clothes, a purple cap, yellow top and blue shirt. The reclining figure wears a red, patterned dress belonging to the artist that suggests traditional African costume. But, for the artist, the red turban is more significant than the dress as this type of headdress, adopted in Britain and the Caribbean alike in the 1970s, reflected a new awareness of African culture inspired by Rastafarianism. For many in the Black community, including Boyce who was greatly attracted by it in the early 1980s, Rastafarianism was akin to the civil rights movement in the USA. It inspired the Black community with a new sense of cultural freedom which took on a religious fervour (see Anthony Giddens, Sociology, Cambridge 1990, p.261).

Rastafarianism developed out of the ‘back to Africa' movement founded by Marcus Garvey in Jamaica in the 1920s. It took hold in Britain in the 1970s when it appealed to a first generation of British-born Black people, who grew up disillusioned by discrimination and hostility. Essentially mystical, the sect based its beliefs on certain sections of the Bible, carving out of the white man's religion a subversive belief system for oppressed Black communities. Of the movement Dick Hebdige writes:

By a dialectical process of redefinition, the Scriptures, which had constantly absorbed and deflected the revolutionary potential of the Jamaican black, were used to locate that potential, to negate the Judaeo-Christian culture which had originally produced those very scriptures. Or, in the more concise idiom of the Jamaican street-boys, the Bible was taken, read and ‘flung back rude'. (Reggae Rastas and Ruddies: Style and the Subversion of Form, Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, University of Birmingham, 1974, p.14)

Rastafarianism was thus a significant Black subculture concerned to redefine Black spirituality and identity. For Black youth it provided a means of rebellion, both against white society and against their parents who they felt continued to accept white oppression. The praying figure, therefore, represents the respectable Christianity of Boyce's family, the reclining figure, the attempt to break with imposed beliefs and behaviour by seeking new alternatives which were, for Boyce, more relevant to a notion of ‘Black culture'.

Through reading about the history of slavery Boyce discovered that her African ancestors practised Christianity while continuing to practise indigenous religions. She read Gert Chesi's bookVoodoo: Africa's Secret Power (trans. Ernst Klambauer, 1980), which explained how African religious beliefs merged with Christianity in South America and the Caribbean to produce voodoo. Chesi writes (ibid., p.5):

Plantation owners and slave dealers had an interest in christianizing the imported slaves: they thought that aggressive reactions on the part of the enslaved people would not occur. They believed the christianized slave was easier to guide and, in accordance with his religion, compliant, subordinated and forbearing. This was the situation in which voodoo was born. Yoruba gods blended with biblical figures, the nature of Christian saints was reinterpreted, African gods were given Christian names, and the system of moral values took its orientation from a concept of god which contrasted with that of the Christian faith ... What at first developed only as a secret protest - mysterious to the slave holders - very soon acquired undreamed-of dynamics of its own.

Dick Hebdige has noted that the ad hoc assimilation of Christianity in the Caribbean was in fact the result of the Black enslaved people being banned from the white man's churches, as they were banned from learning English. The enslaved, therefore, grafted their pagan beliefs onto the new religion in the same way that they developed patois (Hebdige 1974, p.7). These particular cultural forms soon became a means of defiance and resistance, since they excluded the white man.

‘Missionary Position II' addresses Boyce's ambivalence towards the Black church. While she respects her family, she cannot accept their Christian beliefs because, in her view, the history of Christianity and her African ancestors is one of exploitation, a relationship of oppression and submission perpetuated through the church. As she immersed herself in the subject, however, she realised the complexity of trying to understand Christianity, both as an institution and as a religion. These issues were difficult for Boyce to separate and she feels that this lack of clarity is reflected in the finished work.

‘Missionary Position II' was preceded by a closely related work. Regarding ‘Missionary Position I', Boyce has said that it, ‘was in a way me stating my position of contempt for the way in which the church as an institution gets all manner of wealth. For me it's about power relationships, of dominance and submission and I equalled that to gender/sexual roles as well.' Both works have inscriptions which serve both to expand and determine possible meanings. In the case of ‘Missionary Position I' the inscriptions refer to Boyce's own experience of the influence of Christianity through the social institutions of school and the family. When she drew the hand in ‘Missionary Position I', which is pierced like the hand of Christ, Boyce did not imagine it as attached to any particular body. Instead, she saw it as a symbol of white power, power exerted through the Christian faith via these institutions. The texts link the fingers of the white hand to the head and shoulders of a resigned young Black woman (a self-portrait of the artist), whose Rastafarian locks are tied back in a turban head band. The first section of the inscription reads as follows:

Lay-back

Our Father who art in heaven

Hallowed by thy name in command and in control

As children my mother would recite the Lord's prayer at bedtime

This evokes the religious indoctrination she experienced in childhood. The five children of the family recited the prayer together from their several bedrooms, so that it seemed to hum throughout the house. This nightly ritual made a deep impression on the children. The inscription continues:

Them that's got shall get

them that's not shall lose

so the Bible says

and still it's news

These words are from the song ‘God Bless the Child', sung by the American blues singer Billie Holliday (1915-59). The lyrics challenge the Christian idea of the weak inheriting the earth, which the artist felt encouraged people to be subservient. Boyce acknowledges that it may have been useful to quote in the work from the Bible in order to clarify her intended meaning. Such was her antagonism, however, that she could not bring herself to do so.

As a child she had been presented with a Bible at school. The final section of the inscription on ‘Missionary Position I' recalls the impact of this event:

I was really proud when I received a copy of Gideon's Bible at school. Total submission

She felt honoured and pleased to be given a Bible as it represented her acceptance into society. When making ‘Missionary Position I' Boyce was particularly angry about the way in which children were taught about Christianity at school without being given any opportunity to challenge or discuss its beliefs. At no point did she feel able to engage in any critical dialogue, ‘And so in the last bit it says "total submission" which is how I felt about it. It was almost like a fait accompli pertaining to that system of belief, you know, there was no question about it. But the point was that there was for me'. ‘Missionary Position I' was easier for Boyce to resolve because it dealt with the issue of the church as a predominantly white institution. The rebellious stance of ‘Missionary Position I' was maintained in T 05020, but the latter work was more difficult for the artist as she was attempting to express visually a conflict taking place within the black community regarding religious belief.

The various objects depicted in T05020 were carefully selected by the artist as clues to her intended meanings ‘Many of the images I produce are reminiscent of strip cartoons, snapshots etc. in that the image focuses, is edited down, to the essential information required' (quoted in Roberts 1987, p.62). In this case the objects derive from Boyce's family home. The lampstand on the left, for example, has belonged to Boyce's mother since the 1960s. The sofa was one that her mother had owned, if not at the time, then previously. These objects enabled Boyce to suggest a particular kind of environment, one that referred to her parent's home and to the taste of their generation. Although the work is figurative, it lacks much spatial recession. Boyce explained: ‘I always enjoyed the suggestion that something is three-dimensional but the more you look at it the more it defied that three- dimensional possibility and so the floor, for instance, it doesn't even attempt to recede at all. To me it was just a flat surface.'

The wall-paper design which seems to be taken from a palm leaf or fan also appears in ‘Missionary Position I' and other large drawings of the mid-1980s (see, for example, ‘Mr. Close-Friend-of-the- Family Pays A Visit Whilst Every One Else Is Out', 1985, mentioned above). Pattern plays an important role in Boyce's picture-making, as it emphasises the flatness of her pictures and acts as vehicle for meaning. In this instance, Boyce invented the pattern to suggest a type of embossed floral paper over which emulsion is usually painted. The pattern was not meant to dominate the image but it had to be sufficiently prominent in order to make a statement about the taste of the owners. For Boyce this particular pattern is also reminiscent of stained glass windows and, therefore, reinforces the idea of Christian influence in the home.

The paisley carpet pattern is also significant as it lends itself to the theme of cultural imperialism and was deliberately chosen by the artist for this reason. Although it emanated from Asia, the paisley or ‘Persian Flower' design was named after the Scottish town of Paisley, where it was reproduced with great success in the nineteenth century. Paisley has become a quintessentially British design and its history illuminates the kind of cultural appropriation that inevitably occurs with economic and political colonialism.

The ornamental birds placed above the figures appear in many other works by Boyce (see, for example, ‘Halloween', 1985, repr. Roberts 1987, p.58) and particularly in her last large figure drawing of the mid-1980s, ‘She Ain't Holding Them Up, She's Holding On (Some English Rose)', 1986 (repr. Hayward Gallery exh. cat., 1989, p.103). When questioned about the repetition of such motifs in her work Boyce replied that they function as emblems, a ‘shorthand' language for certain meanings. The birds were based on ornamental peacocks made of enamelled metal belonging to her mother which mesmerised Boyce as a child. Critics have asserted that the peacocks represent the opposing views of the two protagonists (see, for example, ‘Black Women Artists: Will the Art Critic Please Step Forward', Spare Rib, no.188, March 1988, pp.9-12). In conversation with the compiler Boyce said:

Well, in my mother's older house they were actually positioned like that and their beaks were open so it looked like they were almost fighting cocks in the way in which they looked ready for action. And so I liked that element of tension within the objects themselves and wanted to use them above the heads of the two figures.

Despite her wish to convey the conflict within the Black community with regard to religious belief, Boyce also wanted to present a sense of continuity. She began to realise that in terms of decoration, many Caribbean homes were unconsciously constructed as shrines. To a certain extent, her mother's home, and those of her mother's generation, represented a cultural continuity with a peculiarly African religious consciousness which they had brought with them from the Caribbean. In this way Boyce discovered an element within Black Christianity with an original ‘Black' identity, and aspects of her mother's taste which reflected that identity. This, however, further complicated her intention to express the conflict between the religious beliefs of her generation and that of her parents.

Boyce's dissatisfaction with Christianity was reinforced through contact with her contemporaries such as Keith Piper, although she is still puzzled why her antagonism to the church should have been so strong. For a long time she favoured the efforts by her contemporaries to establish a ‘modern Afrocentric aesthetic' but has since decided that the idea of returning to a purely African culture is romantic and untenable for those who have experienced the diaspora, that is to say, those whose ancestors were dispersed across the globe by slavery and colonisation. Many of her works, including T05020, relate to her concern about the attitudes of certain sections of the black community regarding the issue of ‘black identity'. Boyce was acutely aware that she risked becoming as dogmatic as those she challenged through her work. Thus, for the artist, the two figures also represent a struggle against the idea of authority and dogma.

Boyce was aware that the issue of British identity was topical in the early 1980s, a social and political phenomenon given impetus by the values of the Conservative government and the Falklands War. It seemed to her that people were referring to a popular stereotype of British identity whereas in reality British identity was pluralistic and multifaceted. Similarly, she noticed that there were a variety of identities or rather, class distinctions, even within the West Indian community in Britain. The objects in her mother's home, for example, denoted working class taste. Since the late 1980s she has shifted the emphasis of her work. In conversation with the compiler she said, ‘I now quite consciously try not to deal with identity because I think what has happened is that any group that names itself automatically puts itself in a box and can only speak from that position'.

The artist has approved this entry.

Published in:

Tate Gallery 1986-88: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions, Tate Gallery, London 1996, pp.278-284 reproduced p.278

Explore

- history(5,776)

- domestic(1,795)

-

- living room(292)

- clothing and personal items(5,879)

-

- turban(39)

- crucifix(42)

- actions: postures and motions(9,111)

-

- arm / arms raised(839)

- eyes closed(34)

- kneeling(502)

- reclining(814)

- woman(9,110)

- black(796)

- Boyce, Sonia(2)

- self-portraits(888)

- religions(181)

-

- Christianity(2,755)

- Rastafarianism(6)

- prayer(102)

- dress: nations/regions(272)

-

- Caribbean(1)

- colonialism(429)

- race(381)

- satire(265)

- inscriptions(6,664)

-

- caption(358)

- religious(17)

- title of work(308)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist, painter(2,545)

You might like

-

Prunella Clough Gate

1981 -

Alexander Mackenzie Drawing, June 1963

1963 -

Leon Kossoff Drawing for ‘Children’s Swimming Pool’

1971 -

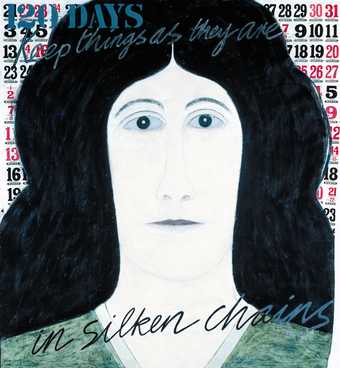

Ian Breakwell Keep Things as They Are: In Silken Chains

1981 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There Was Oil III

1982 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There Was Oil II

1982 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There Was Oil I

1982 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There Was Oil (Beach)

1981 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There was Oil (Car on Beach II)

1981 -

Terry Setch Once Upon a Time There Was Oil (Car on Beach)

1981 -

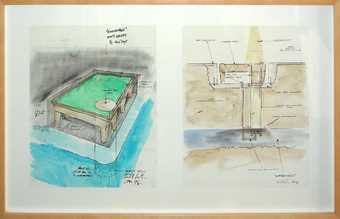

Richard Wilson Watertable

1994