Not on display

- Artist

- Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA born 1934

- Medium

- Acrylic paint, oil paint, acrylic gel, damar, beeswax, chalk, metallic pigments, acrylic foam, shells and plastic toys on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2285 × 2860 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1987

- Reference

- T04889

Display caption

This work reflects Bowling’s interest in paint as ‘organic matter, pliable and beautiful’. He began as a figurative painter, studying alongside artist R B Kitaj. Bowling used foam, shredded plastic packing material, glitter, costume jewellery, plastic toys and oyster shells embedded into the surface to achieve the complex texture in this painting. He has talked about his move from figurative painting to abstraction as a process of ‘unlearning’. Bowling’s belief in the potential expressivity of paint is central to his art practice. Reluctant to attach specific meanings to his works, personal dimensions can sometimes be detected in his use of small plastic toys, left in his studio by friends’ children, and in the titles which often allude loosely to current interests, events and even fellow artists.

Gallery label, October 2022

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

T04889 Spreadout Ron Kitaj 1984–6

Acrylic paint, acrylic gel and mixed media on canvas 2285 × 2860 (90 × 112 3/4)

Inscribed ‘“SPREADOUT RBK” | Frank Bowling | 1986’ on back of canvas t.l.

Purchased from the artist (Grant-in-Aid) 1987

‘Spreadout Ron Kitaj’ has a richly decorated surface, made up of a number of materials. The main media are arcylic gel and acrylic paint, but the artist also used oil paint, damar, beeswax, chalk, and metallic pigments (nickel, silver, gold, rich pale gold, and pearlessence). In addition, acrylic foam, shredded plastic packing material, acrylic-based Christmas glitter, acrylic-based costume jewellery, plastic toys and oyster shells are embedded into the surface of the painting. Beneath the paint-encrusted surface lies a slightly raised circular shape and, less noticeably, straight forms, arranged to lie horizontally, vertically and diagonally, all of which were made from pieces of acrylic foam.

The textured surface of T04889 and, in particular, its use of acrylic foam, places it within a particular phase in Bowling's work which lasted from c.1981 to 1990. His paintings of this period required a slow and complex way of working, which was described by Rachel Scott, writing on behalf of the artist, in a letter dated 10 October 1989:

The cotton duck canvas is tacked to its full length and draped on the wall.

The polyether type foam is cut into strips and glued to the canvas.

A colour ground is flooded into the canvas.

Acrylic gel is applied with spatula and palette knife.

The canvas is transferred to the floor. Paint and acrylic gel are mixed with ammonia and water in equal proportions in containers and then applied.

Sometimes pearlessence and sometimes metallic pigments are added and/or mixed in with the paint.

The paint is applied, shells and plastic toys are embedded in the thick globular acrylic gel.

The painting is left to dry a little for a day or two, depending on room temperature and weather conditions, influenced by the time of year.

The canvas is pulled up and tacked to the wall in stages (low, middle, high). This allows the material on the canvas to move, drip, cascade and slither in a downward motion. More gel, paint, fluorescent chalk, metallic dust are applied as the work goes from stage to stage. When completely dry, oil paint is sometimes but not always applied.

After the work is stretched a thinned mixture of damar crystals and distilled turps is applied. This mixture sometimes includes liquid beeswax.

While a few of the different objects and materials used in the making of Bowling's canvases of this period typically remain clearly identifiable, most are integrated into the painting surface. Writing about the distinctive surface quality of these paintings, Margaret Garlake notes that Bowling's approach is ‘as far removed as it is possible to be from the relative lucidity of collage or assemblage; it produces something more closer to matière painting and is what identifies these works as paintings, rather than objects’ (‘Frank Bowling; Clifford Myerson’, Art Monthly, Sept. 1988, p.20).

Bowling began work on T04889 in 1984, while he was one of six artists in residence at the summer school of painting and sculpture in Skowhegan, Maine. During his nine-week stay there he worked on three large stretches of canvas, all of which were cut up into two or more sections in order to facilitate their transportation. ‘Armageddon’ (repr. Frank Bowling: Paintings 1983–86, Serpentine Gallery, March 1986, [pp.4–5] in col.) is a part of one such canvas which was divided into two. T04889 is the left half of a large piece of canvas which, when Bowling first worked on it, was tacked horizontally to the wall of his studio at Skowhegan. Bowling asked his youngest son, Sacha Jason Bowling, to draw circle shapes onto the wall-mounted canvas (at 6 feet 3 inches, Sacha Bowling could reach a little further than his father, but even so needed to stand on a chair to encompass the full height of the canvas). With a piece of chalk attached to a central point by a length of string, he drew one complete circle (the trace of three-quarters of which is evident in T04889) and three more, broader arcs to one side. Lengths of foam pieces were then stuck on these lines when the canvas was laid on the studio floor.

This way of developing linear elements in his paintings of this period was quite typical. Bowling would often develop shapes from standard geometrical figures, sometimes using the proportions of the Golden Section, or, as in T 04889, the mathematical procedure of creating a circle from a square (as evidenced by the underlying grid structure in the painting). With the ‘Cathedral’ series of c. 1987 (see, for example, ‘Ziltinup’, 1987, the artist, repr. Frank Bowling, exh. cat., Castlefield Gallery, Manchester, June–July 1988, [p.9] in col.), Bowling laid the foam pieces in configurations that were based upon illustrations in a book of architectural ornament. However, Bowling would always slightly alter the arrangement of the foam pieces before gluing them down to introduce a more dynamic or emotionally expressive element into his works. The regularity of the initial design was always further disrupted when, under the weight of the impasto, the foam pieces slipped downwards as the canvases were moved from a horizontal to a vertical position.

While still unfinished, the canvas of which T04889 is a portion was cut in two, rolled up, and brought back to London. In July 1986 he started work again on T04889, finishing it in the autumn of that year. Extra strips of canvas were glued onto the cut edges in order not to lose any of the original image when the canvas was put on a stretcher. The other part of the original canvas was completed in 1987, and was titled ‘Sacha Jason's Quail's Nest’ (quails' eggs are clearly visible in the painting's surface). This second work, which measures 74 1/2 in × 114 in, belongs to the artist (no repr. known).

Bowling's early work was figurative, influenced in part by Carel Weight and Francis Bacon. Bowling moved to New York in 1966, and, although his paintings retained figurative elements until the mid-1970s, he became increasingly interested in the effects created by paint itself. Responding to the work of such American artists as Pollock, Frankenthaler and Morris Louis, he began c.1970 to pour paint onto colour grounds. He found that laying the canvas on the floor allowed him to provoke controlled accidents and unexpected effects, and he increasingly used drips and splashes of paint to create surface patterns.

By 1972 Bowling was committed to a formalist aesthetic. Later he acknowledged that the sort of art championed by the American critic Clement Greenberg (‘the sculpture of Michael Steiner and Anthony Caro, the paintings of Jules Olitski, Larry Poons' work’) was ‘the kind of art which I, too, practice and admire’ (Frank Bowling, ‘Formalism: A Selective View’, Cover, no.6, Winter 1981–2, p.40). For Bowling, the material structure of paint was potentially highly expressive. As early as 1972 he described paint as ‘organic matter, pliable and beautiful’, with the capacity ‘to engage, demonstrate, and distribute major weights like imagination, articulation, understanding and delivery’, independently of the appearances of nature (Frank Bowling, ‘Revisions: Color and Recent Painting’, Arts Magazine, Feb. 1972, pp.49, 46). More recently, he has spoken of paintings containing energy which is ‘trapped in the web of skeins and layers of the material being worked’ (see Mel Gooding, ‘Frank Bowling: Soundings Towards the Definition of an Individual Talent’, in The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, exh. cat., Hayward Gallery 1989, p.121).

Bowling's belief in the potential expressivity of paint is central to his impasto works, which are animated by rugged paint textures and residues of splashes and drips. From c. 1981 Bowling used a thick acrylic gel to give extra body to his impasto surfaces, and to hold the various materials he wanted to embed in his paintings. The American abstract painters Jules Olitski and Larry Poons had used the impasto surfaces created by this acrylic gel to explore the relationships between figure and ground, opticality and surface structure; and Bowling identified closely with these artist and their aspirations. Bowling began to incorporate strips of acrylic foam (offcuts acquired from manufacturing firms such as upholsterers) into his paintings in 1981, though it took him several years to resolve the technical problems involved in fixing these pieces to the canvas surface. Although rectilinear formations predominate in his work, there are a number of works of this period which, like T 04889, incorporate large arc shapes, for example, ‘Squashed Unicorn’, 1983 and ‘Armageddon’, 1984 (the artist, repr. Serpentine Gallery exh. cat., 1986, [pp.4–5] in col.), and ‘Philoctetes Bow’, 1987 (the artist, repr. Castle-field Gallery exh. cat., 1988, [p.8] in col.) Bowling stopped using pieces of acrylic foam in early 1990, and since then has used, instead, acrylic gel, applied with a spatula, producing a much reduced impasto.

Notwithstanding the formalist aesthetic that underpins Bowling's art, the surface qualities of his paintings and, above all, their vibrant colours evoke associations of place and atmosphere. Critics have related the sometimes tropical colours of his paintings to the landscape of his native Guyana, which he left at the age of fourteen, and, more generally, to the experience of nature, the surface sheen of his paintings sometimes suggesting organic matter in a state of decay. Ambivalent about such interpretations, Bowling has always hesitated to discuss the figurative or personal meanings of his paintings. However, an autobiographical dimension to his work can be sometimes detected in his use of such items as small plastic toys, left in his studio by friends' children, and, more especially, in the titles of the works which often allude, albeit tangentially or light-heartedly, to current interests or events.

In a letter to the Tate Gallery, dated 1 December 1986, Bowling explained the origins of the title of T04889, which refers to the American-born artist R.B. Kitaj:

‘Spreadout Ron Kitaj’ was inspired by a West Indian song (Jamaican reggae-rock?) heard on [the] car radio and seemed so appropriate. Earlier that very day I'd received a long, amusing and sympathetic letter from Kitaj dated ‘September’ and written by hand on blue lined yellow paper. This letter lit up my life, my spirits immediately before being so very low. The song, sounding like a chant exhorting a leader, someone the reverse of an ayatollah, to go out and spread the word - or a captain motivating his team.

Bowling had been a student with Kitaj at the Royal College of Art, London, from 1959 to 1962, and saw his work as closer in spirit to Kitaj's than to that of other young Royal College artists, such as David Hockney or Derek Boshier. About this period, which saw the beginnings of the British Pop movement, Bowling has said:

We were all painting from newspaper cuttings, photographs, films, etc, but I wasn't allowed to be a Pop artist because of their preoccupation with what was Pop. Mine was to do with political things in the Third World ... I did not paint Marilyn Monroe because she did not interest me. Kitaj did not paint Marilyn Monroe either; he painted ‘The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg’. Kitaj was closest to me in political preoccupation.

(quoted in Hayward Gallery exh. cat., 1989, p.39)

Bowling lost touch with Kitaj during the 1970s, but was greatly cheered to receive a note of praise and congratulations from him at the time of his exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery, in March 1986.

In conversation with the compiler on 27 March 1992, Bowling explained that he had not been paying much attention to the lyrics of the reggae song he heard on the car radio, but the rhythm of the words suggested to him ‘Ron Kitaj’. It pleased him to use this musical connection in the title of T04889 as he always hoped his abstract paintings would ‘deliver’ their impact in much the same way as music does. Bowling also said that the word ‘spreadout’ in the title had no particular connection with the action involved in drawing the circle shape in the painting, but was the sort of word familiar to the artist from his days as a footballer when he would shout it out to other players in encouragement and exhortation (which was how he had interpreted Kitaj's letter of praise). In his letter to the Tate Gallery Bowling wrote that he might have titled T04889 simply ‘Homage to RBK’, but, ‘my feeling is that the present title slightly pounding in my troubled ear is more in keeping with the spirit of things’.

This entry has been approved by the artist.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- figure(2,270)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- colour(2,481)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- gestural(763)

- head / face(2,497)

- Kitaj, R.B.(8)

- individuals: male(1,841)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist, painter(2,545)

You might like

-

Richard Hamilton Four Self Portraits - 05.3.81

1990 -

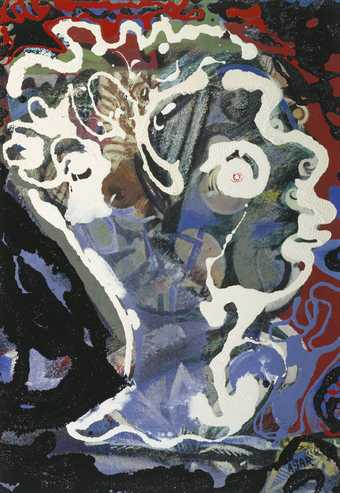

Eileen Agar Head of Dylan Thomas

1960 -

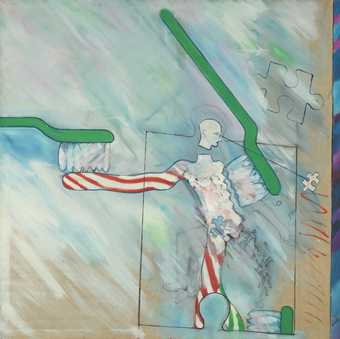

Derek Boshier The Identi-Kit Man

1962 -

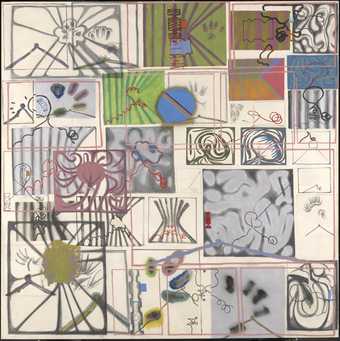

Bernard Cohen Matter of Identity I

1963 -

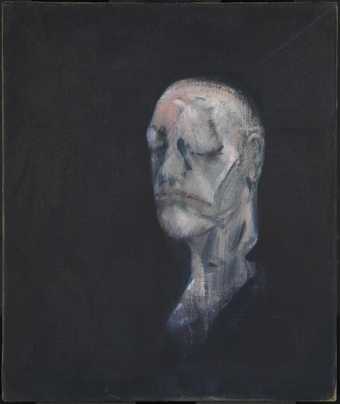

Francis Bacon Study for Portrait II (after the Life Mask of William Blake)

1955 -

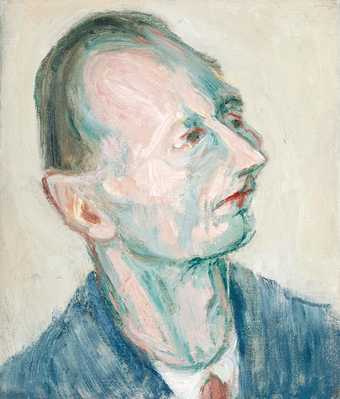

Sir Lawrence Gowing Portrait of Sir Norman Reid

1980 -

R.B. Kitaj Cecil Court, London W.C.2. (The Refugees)

1983–4 -

Louis Le Brocquy Image of James Joyce

1977 -

Helen Lessore Portrait of David Wilkie

1967 -

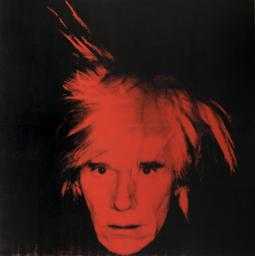

Andy Warhol Self-Portrait

1986 -

Avis Newman The Wing of the Wind of Madness

1982 -

Julian Schnabel Homo Painting

1981 -

Art & Language (Michael Baldwin, born 1945; Mel Ramsden, born 1944) Portrait of V.I. Lenin with Cap, in the Style of Jackson Pollock III

1980 -

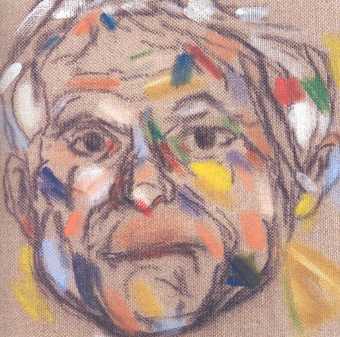

R.B. Kitaj Self-portrait

2007 -

Sir Frank Bowling OBE RA Rachel IV

1989