In Tate Britain

Prints and Drawings Room

View by appointment- Artist

- Francis Bacon 1909–1992

- Medium

- Graphite and oil paint on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 339 × 263 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund and a group of anoymous donors in memory of Mario Tazzoli 1998

- Reference

- T07352

Display caption

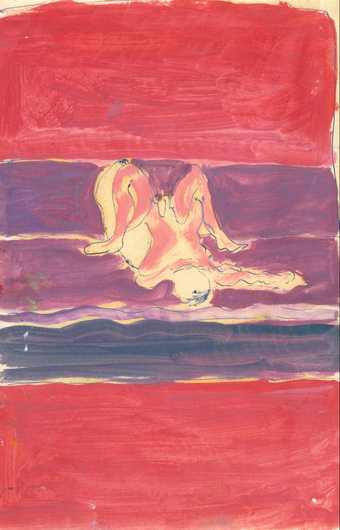

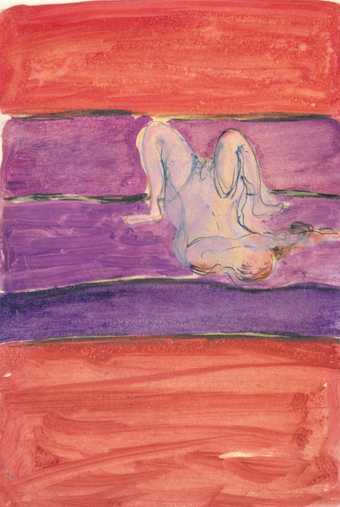

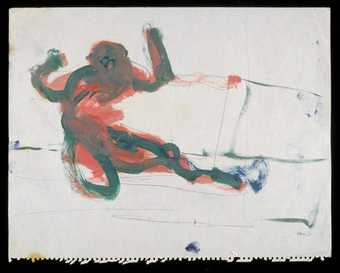

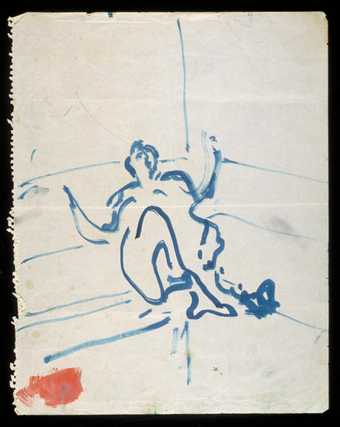

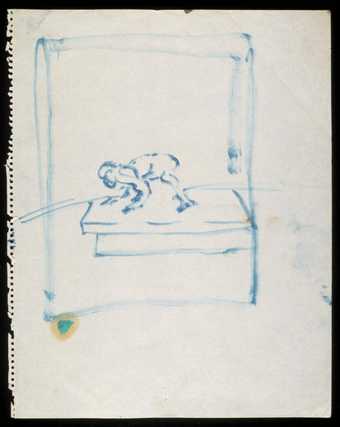

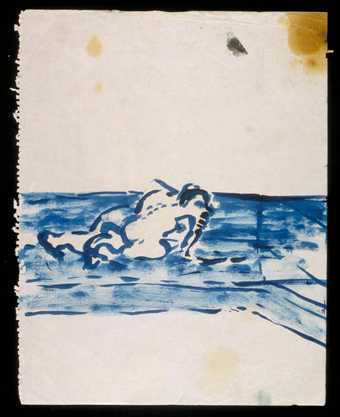

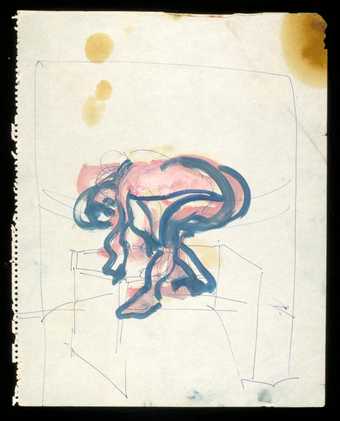

The dynamism of Bacon's studies of the body is evident in 'Turning Figure'. Preliminary pencil sketching was obliterated by energetic pink and green paint, with the precariousness of the body anchored by the stable green frame. In general terms, the sketch relates to a number of 1962 oil paintings (from which the title has been borrowed). The complications of the poses were associated by John Russell with Bacon's observation that 'Painting makes me more aware of behaviour'.

Bacon gave this work to the poet Stephen Spender, who wrote a number of articles on him around 1961. It was accompanied by 'Figure in a Landscape' and the pair of 'Reclining Figures', also in this display.

Gallery label, September 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Oil and graphite on paper

339 x 263 (13 3/8 x 10 3/4)

Purchased from Lady Natasha Spender with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Art Collections Fund and a group of anonymous donors in memory of Mario Tazzoli, 1998

Provenance:

Given by the artist to Stephen Spender (early 1960s) and thence by descent

Exhibited:

Francis Bacon, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, June-Oct.1996, Haus der Kunst, Munich, Nov.1996 - Jan.1997 (93, repr. in col. p.234)

Francis Bacon: Working on Paper, Tate Gallery, London, Feb.-April 1999 (2, repr. in col. on cover and p.39)

Literature:

Fabrice Hergott and Hervé Vanel in Francis Bacon, exh. cat., Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris 1996, p.235

Richard Morphet, ‘Francis Bacon: 38 Unique Works on Paper; Four Unique Works on Paper’, National Art Collection Fund 1997 Review, London 1998, pp.99-100, repr. p.99

Matthew Gale, ‘Points of Departure’, in Francis Bacon: Working on Paper, exh. cat., Tate Gallery, London 1999, pp.13, 15, 30-1

Reproduced:

Richard Cork, ‘I can’t draw, said Bacon’, Times, 26 Jan. 1998, p.18

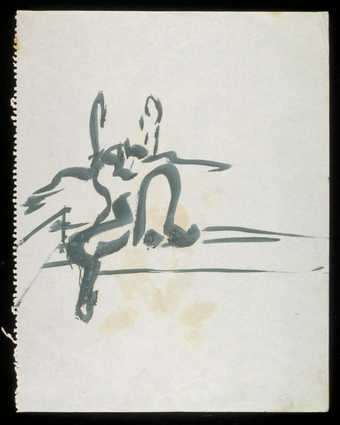

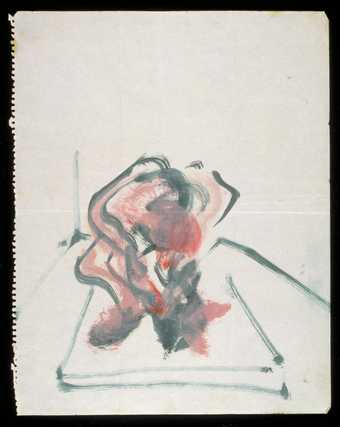

When this sketch first emerged in public, Fabrice Hergott and Hervé Vanel wrote of the energetic draughtsmanship: ‘la couleur ne remplit pas strictement un tracé nerveux au crayon relevant plus d’une impulsion dynamique que d’un contour préliminaire.’ (‘the colour does not strictly fill a nervous pencil line, revealing a dynamic impulse rather than a preliminary contour.’) They noted particularly how the green outlines on the pink flesh also departed from the original pencil line, so that the three stages resulted in a superimposition of complementary elements. Such energy - evident from the first in the heavy use of the soft pencil - has encouraged Richard Morphet to characterise the image as ‘Dionysiac’, so that the abandon of the female nude evokes classical Maenads. This may be associated with Bacon’s sustained investigation of the fixing of movement which had its origins in his use of photographic images but which John Russell identified as attempting more complicated poses in the years before 1963. The ‘twist and turn’ that he noted was achieved ‘sometimes on a revolving chair, sometimes with no apparent means of support ... sometimes in something like formal contrapposto, the figures are caught in the act of turning through 360 degrees’. Russell concluded by citing Bacon’s statement that ‘Painting makes me more aware of behaviour’.

Russell observed that ‘the act of turning’ became ‘the named subject of a painting’ Turning Figure, 1963 (private collection). In describing it as ‘wound round and round itself like barley sugar’, he characterised the concentration of energy in the balancing figure. This is equally applicable to three related canvases of the preceding year. The Tate’s work on paper has been shown as Turning Figure c.1962 and is now known as Sketch [Turning Figure] c.1959–60. The former title and date implicitly established a link with these canvases even though its ‘Dionysiac’ figure is in distinct contrast to their tense nudes; as Hergott and Vanel have commented, the drawing is difficult to place in relation to the canvases. Although the framing green square may be related to elements in the oil paintings which establish the standing position, it is equally possible to relate the figure in the sketch to that of Nude, 1960 (private collection). There another female nude, though balanced on one leg, is evidently to be read as seated. Given Bacon’s continued abandonment of canvases, it may be that the sketch was made in preparation for a destroyed painting.

The independence of this image from any known oil painting shows that Bacon used sketches to explore compositions. This would be unremarkable were it not for his categorical denial of such a practice in 1962, which - in combination with campaigns of destruction - helped to keep them secret. The issues surrounding this dissembling have been discussed in relation to Sketch [Figure in a Landscape] c.1960 (T07351), a work which, like Sketch [Turning Figure], survived through being acquired by the writer Stephen Spender. The resulting mounting of the work, with patches of tape at the corners, is now visible, as is a stroke on the reverse (at the right) which indicates that the drawing was always in a rather rough condition.

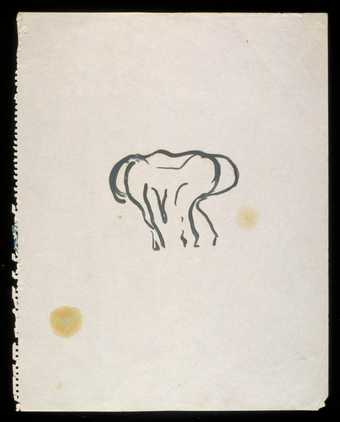

Even while the dating of the works on paper remains approximate as a result of the secrecy surrounding their production, it may be concluded that Bacon made preparatory works at least in concentrated campaigns during his career. In this connection, it is particularly significant that the media and colouring of Sketch [Turning Figure] are very close to those of the group of twenty-six leaves from a sketchbook which is presumed to be contemporary (T07355-T07380).

Matthew Gale

May 1998

Revised February 1999

You might like

-

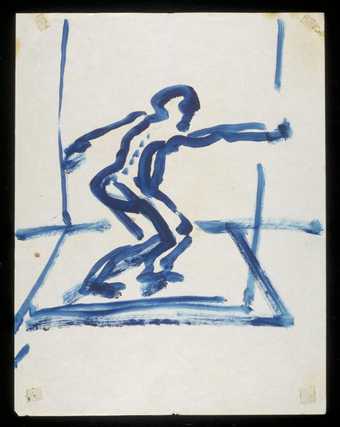

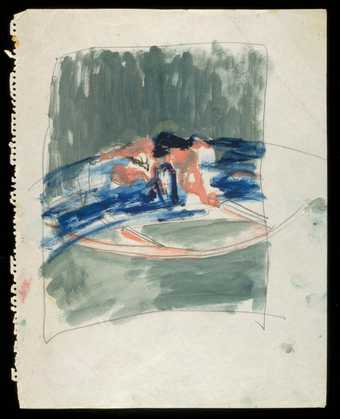

Francis Bacon Sketch [Reclining Figure, No. 1]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Reclining Figure, No. 2]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Collapsed Figure]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure Bending Forwards]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Falling Figure]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure with Arms Swung Out]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure Lying Flat]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure in Grey Interior]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Fallen Figure]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Bending Figure, No. 1]

c.1959–61 -

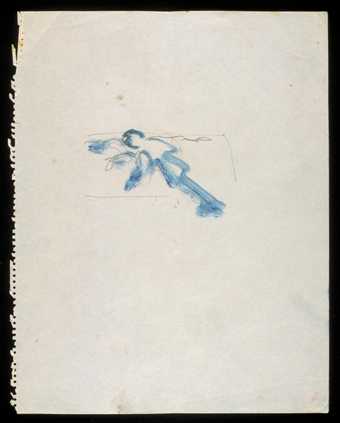

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure Crawling]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure Lying, No. 1]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure Lying, No. 2]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Blue Crawling Figure, No. 2]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Bending Figure, No. 2]

c.1959–61