In Tate St Ives

- Artist

- Francis Bacon 1909–1992

- Medium

- Oil paint and ink on paper

- Dimensions

- Support: 238 × 156 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund and a group of anonymous donors in memory of Mario Tazzoli 1998

- Reference

- T07353

Display caption

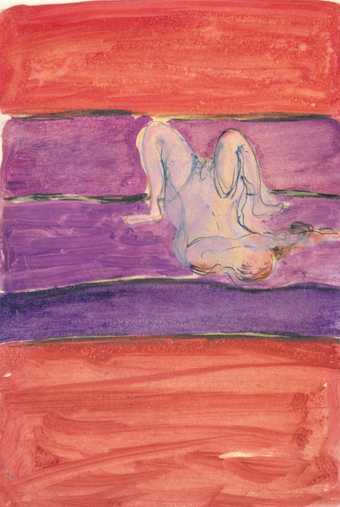

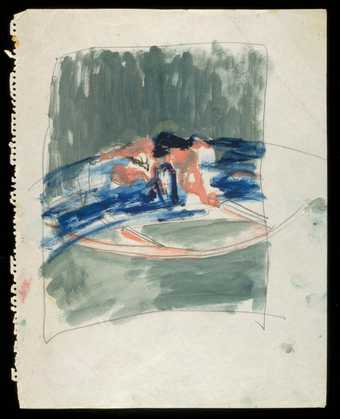

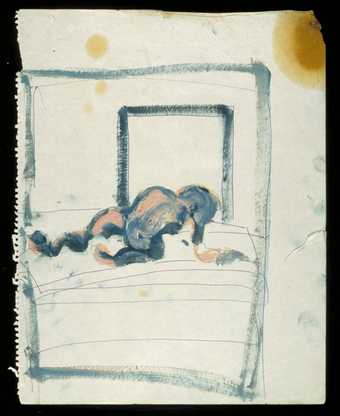

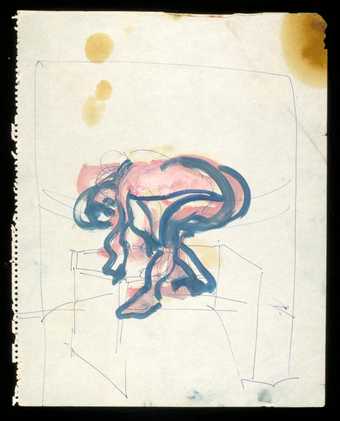

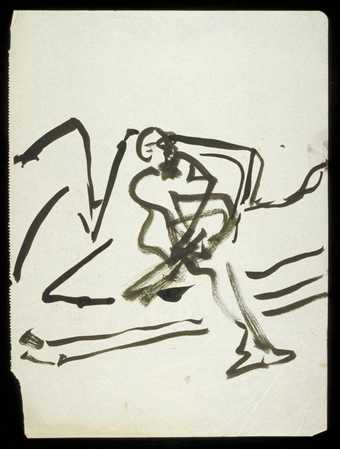

These two works on paper by Bacon are the only ones in the display in which the page has been filled. As the pose remains the same, they may have served as colour studies and may even be a response to Mark Rothko's contemporary work (seen in London in 1959). The male nude, and the horizontal bands (derived from a sofa against a wall) are common to a series of Bacon's oil paintings from 1959 and 1961. The sketches appear to be later, as an impression of writing from another sheet but visible on 'Reclining Figure, no.1' gives his address as '7 Reece Mews', the studio which he occupied in the autumn of 1961.

Gallery label, September 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Gouache and ballpoint pen on paper

235 x 154 (9 1/4 x 6 1/16)

Purchased from Lady Natasha Spender with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, the National Art Collections Fund and a group of anonymous donors in memory of Mario Tazzoli, 1998

Provenance:

Given by the artist to Stephen Spender (early 1960s) and thence by descent

Exhibited:

Francis Bacon, Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, June-Oct.1996, Haus der Kunst, Munich, Nov.1996 - Jan.1997 (94, repr. in col. p.236, as ‘c.1963’)

Francis Bacon: Working on Paper, Tate Gallery, London, Feb.-April 1999 (3, repr. in col. p.40)

Literature:

Fabrice Hergott and Hervé Vanel in Francis Bacon, exh. cat., Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris 1996, p.235

Richard Cork, ‘I can’t draw, said Bacon’, Times, 26 Jan. 1998, p.18 (repr. as Reclining Figure)

Richard Morphet, ‘Francis Bacon: 38 Unique Works on Paper; Four Unique Works on Paper’, National Art Collection Fund 1997 Review, London 1998, pp.99-100, repr. p.99

Matthew Gale, ‘Points of Departure’, in Francis Bacon: Working on Paper, exh. cat., Tate Gallery, London 1999, pp.13, 15, 31-2

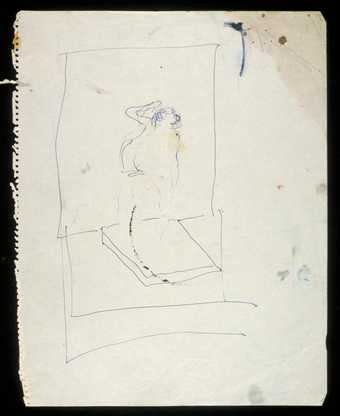

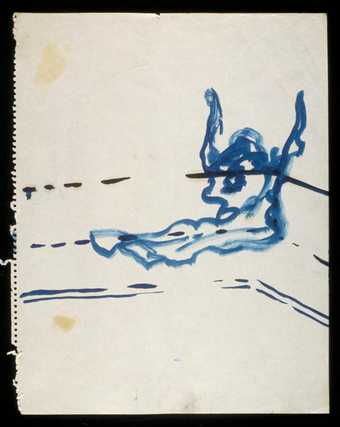

Within Bacon’s oeuvre Sketch [Reclining Figure, No. 1] and its companion Sketch [Reclining Figure, No. 2] (Tate Gallery T07354) are unusual both in being painted in gouache and in their close relationship to oil paintings. The survival of a few pre-war watercolours reveals the artist’s early method and, since his death, the emergence of further works on paper from the 1950s and 1960s has confirmed that this practice continued to some extent. Bacon himself denied making preparatory sketches, but this was complicated by the fact that the two Reclining Figure gouaches, like Sketch [Figure in a Landscape] c.1960 (T07351) and Sketch [Turning Figure] c.1959–61 (T07352), were owned by the writer Stephen Spender from the early 1960s. Their status even seems to have been ambiguous for the artist, who is reported to have told Spender ‘I have always wanted you to have something of mine’, a statement which implies a certain status for such sketches. In this distribution, the works were proclaimed as an open secret even as they remained unexhibited. This situation lends the emerging works on paper an ambivalent but revelatory status. On the one hand, the painter did not consider them as works of art to be acknowledged publicly, but, on the other hand, they expose an aspect to his working method hitherto little known.

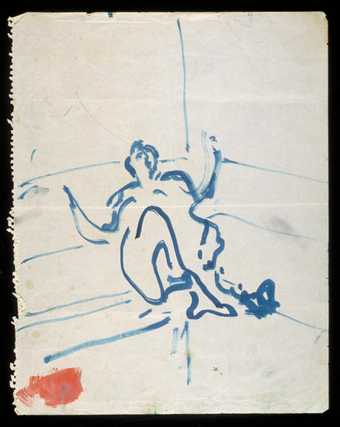

Both gouaches were painted on sheets of sketchbook paper with perforations along the sides. The male figure was drawn with an ordinary ballpoint pen, and adopts an unusual posture: reclining with cranked round legs which raise the hips. Ernst van Alphen has called a related pose ‘the embodiment of sexual desire’, and certainly it affords an explicit display of genitalia as well as a more general atmosphere of hedonism. A similar pose - although with one leg extended - was used for Reclining Woman, 1961 (Tate Gallery T00453) and three closely related canvases of 1959. This relationship is reinforced by the horizontally striped backgrounds found in the gouaches, which comply with the progressively abstracted settings used in the oil paintings. The secrecy surrounding the sketches makes their dating approximate, but such a compositional coincidence, which has been recognised by Fabrice Hergott and Hervé Vanel, would tend to place them in 1959-61. Close inspection of Sketch [Reclining Figure, No. 1] provides other evidence, as it bears the impression of Bacon’s handwriting from a letter and ‘Reece Mews | SW7’ is clearly visible at the top. As he did not move to this Kensington studio until the autumn of 1961, this securely places it after that date. How long after is not clear, although the gift of the drawings may be associated with Spender’s writings on the painter in 1961-2. Three lines at the base of the sheet also have legible impressions: ‘[?by] 15 or Thursday 16 | I’m here all day | faithfully’. This may refer to Thursday 16 November 1961.

Despite the association with Reclining Woman – and prior to this discovery - the pair of gouaches were previously dated as c.1963. This was presumably on the strength of the relation of the pose - and especially the position of the legs, as Richard Morphet has remarked - to the slightly later Lying Figure with Hypodermic Syringe, 1963 (private collection), although the latter appears to be a woman situated on a quite distinct free-standing bed. While their text accompanied the dating of the gouaches to c.1963, Hergott and Vanel reserved judgement. They commented that ‘il demeure difficile de situer ces dessins dans le processus de métamorphose qui s’opère dans ces années entre une figure manifestement masculine (probablement Peter Lacy) et une figure au sexe irrésolu sans aucun doute inspirée de photographies d’Henrietta Moraes’. (‘it remains difficult to situate these drawings in the process of metamorphosis which took place in the years between a manifestly masculine figure (probably Peter Lacy) and a figure of unresolved sex undoubtedly inspired by photographs of Henrietta Moraes’.)11 David Sylvester, who helped to date the works, has since revised his dating in order to relate it more closely to the 1959 and 1961 canvases. It remains unclear whether they were made in preparation for these canvases or, perhaps more likely, whether they proposed compositional variations after the completion of the paintings.

The differences between the pair of gouaches are found in the colouring of the setting which appears to be a sofa. In Sketch [Reclining Figure, No. 1], the body was set against five bands of strong hues: red above and below, sandwiching grades of purple. In the absence of any linear device, the changing colours establish the space in conjunction with the inclination of the body. More so than Reclining Woman (where a sofa is suggested by marginal details), this is reminiscent of the colour field paintings of Mark Rothko which were familiar in Britain by the late 1950s. It is possible that two sketches served as working trials for variations in the background of larger compositions and, even if such canvases do not survive, this exposes the relative orthodoxy of Bacon’s working method.

Matthew Gale

May 1998

Revised February 1999

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- colour(2,481)

- domestic(1,795)

- furnishings(3,081)

-

- couch(203)

- male(959)

You might like

-

Francis Bacon Figure in a Landscape

1945 -

Francis Bacon Reclining Woman

1961 -

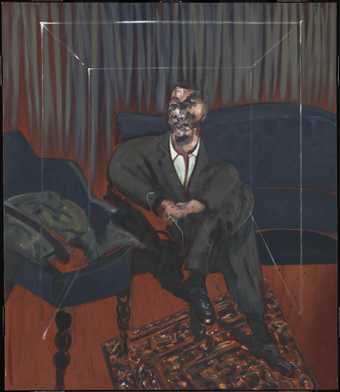

Francis Bacon Seated Figure

1961 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Reclining Figure, No. 2]

c.1959–61 -

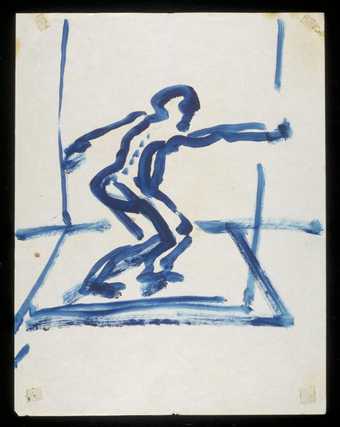

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure with Arms Swung Out]

c.1959–61 -

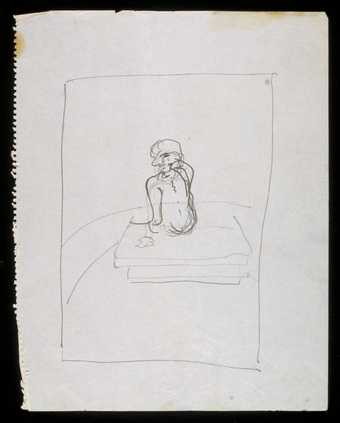

Francis Bacon Sketch [Seated Figure]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure in Grey Interior]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Standing Figure]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure with Foot in Hand]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Fallen Figure]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Fallen Figure with Arms Up]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Figure Lying, No. 1]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Pink Crawling Figure]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Bending Figure, No. 2]

c.1959–61 -

Francis Bacon Sketch [Man on a Sofa]

c.1959–61