If ontology is to be other than a philosopher’s game, it must reflect the ‘what’s and why’s’ informing the esteem that draws us to art works.

Stephen Davies 20011

This paper focuses on questions about authenticity, change and loss in relation to time-based media installations.2 The term time-based media refers to works that incorporate a video, slide, film, audio or computer based element. Time-based media installations involve a media element that is rendered within a defined space and in a way that has been specified by the artist. Part of what it means to experience these works is to experience their unfolding over time according to the temporal logic of the medium as it is played back. As we shall see, the fact that these works are installations has perhaps a greater impact on the development of a conceptual framework for their conservation than the fact that they involve time-based media.

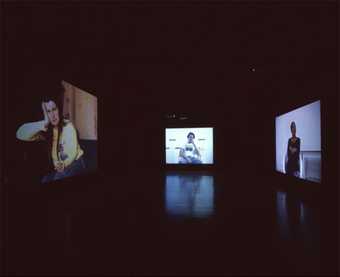

Fig.1

Sam Taylor-Wood

Killing Time 1994

Installed at Tate Britain 2003

Courtesy Tate 2006 © Sam Taylor-Wood

A conceptual framework for traditional fine art conservation

The nineteenth century saw the establishment of many of the ideas formative in the development of the professional discipline of conservation that continue to underpin our understanding of conservation to this day. As Salvador Muñoz-Vinas has recently written in Contemporary Theory of Conservation:

In the nineteenth century, the ideas of the enlightenment gained momentum and wide recognition: science became the primary way to reveal and avail truths, and public access to culture and art became an acceptable idea; romanticism consecrated the idea of the artist as a special individual and exalted the beauty of local ruins; nationalism exalted the value of national monuments as symbols of identity. As a result, artworks – and artists – acquired a special recognition, and science became the acceptable way to analyse reality.3

Despite the dematerialisation of the art object4 in the 1960s and the exploration of the idea of artworks or cultural objects as clusters of meanings in contemporary conservation theory,5 artworks are commonly conceived as unique physical objects. In conservation the prevalent notion of authenticity is based on physical integrity and this generally guides judgments about loss. For the majority of traditional art objects, minimising change to the physical work means minimising loss, where loss is understood as compromising the (physical) integrity of a unique object. Where this conception of conservation is most contested is in ethnographic and contemporary art conservation.

Defining the purpose of conservation

Salvador Muñoz Viñas has described traditional conservation as a ‘truth-enforcement’ operation, which is accompanied by the attending notion of an ‘original condition’.6 In fine art conservation the condition of the object when it entered the collection, or even some notion of its state when it left the studio, may act as the conservator’s reference ‘original’ condition. This ‘original condition’ is considered to be akin to an original state against which change can be measured.

This notion of the original object is part of a conceptual framework that posits the idea that the natural sciences provide a logical model for gaining objective knowledge of an object.7 This idea of conservation has been widely debated in recent years and much of the critical thinking has come from those working with heritage sites and ethnographic collections. This recent critical thinking has emphasised the idea of conservation as a social process, and no longer the objective acts of an impartial conservator engaged in truth enforcing activity.8 The two very different concepts of the role of the conservator have been captured by the notion of conservation as narrowly and broadly defined. The narrower definition is reflected in the following expressions of the purpose of conservation cited by various professional conservation bodies from around the world:9

Conservation is the means by which the original and true nature of an object is maintained.10

Conservation is the means by which the true nature of an object is preserved.11

Preservation is action taken to retard or prevent deterioration of or damage to cultural properties by control of their environment and/or treatment of their structure in order to maintain them as nearly as possible in an unchanging state.12

The broader understanding of conservation is captured in the definition given in the Nara Document on Authenticity, which defines conservation as ‘all efforts designed to understand cultural heritage, know its history and meaning, ensure its material safeguard and, as required, its presentation, restoration and enhancement.’13 This is contrasted with a narrow definition that is firmly focused on the material aspect of the object; as such the narrower definition refers to an activity included in the broader definition.14

Fine art conservation has found it particularly difficult to let go of the materially focused, self-contained aesthetic object of conservation, as narrowly defined. This is, in part, due to the concept of the artwork as developed in the eighteenth century and the pervasive nature of the philosophy of art and aesthetics that accompanied it.

The concept of an artwork

Prior to the Romantic conception of a work of art, there was little by way of a distinction between art and craft. Art depended for its significance on something extraneous, for example, God or Nature. ‘All the arts came quickly to be seen both as the motivation and as the end of a unique form of human experience – the pure aesthetic experience.’15 The development of the Romantic aesthetic changed this and characterised artists as being in touch with something transcendental in the creation of their works and gave an independence to works of art as ends in themselves.

Three kinds of integrity exist within conservation as narrowly defined:

Physical integrity refers to the material components of the object, which cannot be altered without violating it. Aesthetic integrity describes the ability of the object to produce aesthetic sensations upon the observer; if this ability is modified or impaired, the aesthetical integrity of the object is thus altered. Historical integrity describes the evidence that history has imprinted upon the object – its own particular history.16

These concepts of integrity are all underpinned by aesthetic empiricism, a term coined by Gregory Currie. ‘Aesthetic empiricism in its purest form is the thesis that the focus of appreciation is what we may term the ‘manifest work’ – an entity that comprises only properties available to a receiver in an immediate perceptual encounter with an object or event that realises the work.’17

The key concepts, which form the framework for traditional fine art conservation, are the ‘conservation object’ (‘the things upon which conservation activities are performed’18 ), authenticity, and authorship. These concepts form the basis against which the purpose of conservation is defined.

The notion of a conservation object

Any discussion of damage or loss quickly moves into the realm of ontology in the need to define change against something perceived as the identity of the work. The conservation object is still largely an object of the Enlightenment, an object that can be known through scientific analysis. A traditional ‘conservation object’ is an object which has been studied scientifically and for which has been established what is known as its ‘state’. ‘The term ‘state’ is intended as a description of everything that can be defined or discovered about an object by observation, measurement or analysis. It is an attempt to define properties that are intrinsic, objective, impersonal, and in distinct contrast to the properties of ‘value’.19

Within this conceptual framework, change is understood with reference to the state of the object, and change that is irreversible and undesirable is defined as damage or loss. For traditional conservation the identity of the work is understood in terms of its material identity and this is considered the proper focus of conservation. It operates within a scientific paradigm where the conservator carefully avoids being lulled into interpretation. The practice associated with interpretation is restoration, which is seen as essentially unscientific and rather frivolous or unprofessional. In this model the conservation object is a unique object, which contains material evidence that enables authentication. Such objects are collected by museums as the ‘tangible traces left by our ancestors.’ 20

Authenticity and authorship

In museum terms an authentic object represents ‘the real objects, the actual evidence, the true data as we should say, upon which in the last analysis the materialistic meta-narratives [of European culture] depend for their verification.’21

Traditionally, discussions of authenticity have focused on material originality and completeness:

Authenticity has been generally considered to mean genuine in terms of materials, workmanship and date, and processes used to authenticate objects concentrated on the identification of raw materials, the examination of tool marks and other aspects of construction, and, where possible, the use of scientific dating techniques. 22

Traditional objects of conservation lend themselves to a notion of authenticity, which might be determined as a matter of scientific precision. A conservator might be able to draw upon precise scientific analysis to establish that a particular object was a member of a particular class of objects. Authenticity admits of degrees. At one end of the spectrum questions of authenticity may be absolute, such as whether this metal is gold. At the other end of the spectrum something might be classified as an authentic instance of X because it satisfies the minimum criteria for membership of a class of Xs. These criteria are often contested.

Many of the discussions around authenticity in relation to fine arts relate to forgery and attempts to pass off by deception a work of art as attributed to a person, time or culture. This notion of authenticity and forgery is particularly relevant to the world of unique precious objects which hold within them evidence that causally links the object back to the hand of the author. Authentic objects provide us with a direct link to a particular past and in this sense authentic means ‘not a forgery’.

With traditional fine art objects, material evidence is sought for authenticity, demonstrating the hand of the artist. In contemporary art, with the demise of the evidence of the hand of the artist, artists have found other means by which to maintain authority and control over their works via certificates and editions.23

The philosopher Nelson Goodman made the distinction between forgeable and non-forgeable arts a key distinguishing marker between autographic and allographic works.24 Autographic arts are things like paintings and sculpture and allographic arts are things like musical or theatrical works that are performed. I would suggest that the concept of authenticity operating in the traditional conceptual framework of conservation is appropriate for a framework in which the objects of conservation are the autographic arts but inadequate for works which are not.

What is emerging is a conceptual dependency between the ontological framework in which an object is classified and described and the attending concept of authenticity. If the ontological framework is focused on the material so will the notion of authenticity. If the ontological framework shifts, then we expect a similar shift in our concepts of authenticity, change and loss.

A different conceptual framework for the conservation of time-based media works of art

The conceptual framework of traditional fine art conservation is focused on material objects that can be known through scientific analysis and that contain evidence of authenticity and of the hand of the artist. The material object is the root of an aesthetic experience and the conservator is charged with being true to the ‘original’ work. As I have previously suggested, this conceptual framework does not sit well with time-based media installations which are in part, both temporal and ephemeral. In what follows I shall look to the philosophy of music to explore alternative ways of understanding authenticity, change and loss in ways that might help to guide the conservation of these works of art.

The object of conservation

Time-based media installations exist on the ontological continuum somewhere between performance and sculpture. They are similar to works that are performed, in that they belong to the class of works of art, which are created in a two-stage process. They share this feature with western notated music where what is experienced is the performance. Similarly, in the case of a time-based media installation, the work must be experienced as an installed event, which again has parallels with a performance. In terms of the parameters of change, the notion of a performance has a different logic than that of the traditional conservation object, and works that are performed allow for a greater degree of variation in the form they take. In discussions of music the concept used to discuss the parameters of acceptable change is ‘identity’ rather than conservation’s material notion of the ‘state’ of the object.

Identity, authenticity and musical performances

In the tradition of Western music, works have a score and for the philosopher Stephen Davies, this is ontologically significant: ‘a performance of a given work is authentic if it faithfully instances the work, which is done by following the composer’s work-determinative instructions as these are publicly recorded in its score.’25

A score, according to Davies, is a notation that has the function of specifying works. A score is intended as instructions to potential performers and ‘it is by following these instructions that players generate instances of the work.’26 Davies also believes in an account of the ontology of musical works which links them to their historical context: ‘the proper interpretation of a score requires knowledge both of conventions for the notation and of the performance practice shared by the composer with the musicians to whom the score is directed.’27 Performances can occur in different times and different places with different performers and still be authentic instances of that performance. In the performance of a musical work it is recognised that there is a gap between a work as represented as a score and its performance. This allows us to speak of good and bad performances while still being able to say that a work is the same work even if badly performed. There is room for interpretation.

Comparing musical works and time-based media installations

Firstly, there is no convention for specifying the work-determinative features of a time-based media work in the same way as there is a score for Western musical works. In his discussion of musical works and performances, Davies introduces the idea that musical works can be ‘thinly’ or ‘thickly’ specified: ‘Works for performance can be “thick” or “thin” in their constitutive properties. If it is thin, the work’s determinative properties are comparatively few in number and most of the qualities of a performance are aspects of the performer’s interpretation, not the work as such.’28 Davies uses the terms ‘thin’ and ‘thick’ to indicate the degree to which the composer has determined the detail of the performance through work-determinative instructions, for example, how much direction the composer has given to the performers via the score and the degree of additional direction regarding instrumentation. The concept of a ‘thinly’ and ‘thickly’ specified work can also usefully be applied to time-based media installations.

In time-based media installations, ‘thickly’ specified works are works where the artist has specified the qualities of the work and its presentation as precisely as possible. Unlike conventional musical or theatrical works, time-based media installations operate more like sculpture in that the artist rarely sees him or herself working within a context that allows for interpretation in the way that a composer or a playwright might. Performers are not part of the equation. This has led some to argue that the realisation of an installation in the gallery is not significantly different from hanging a painting. A time-based media installation, they would argue, can be well or badly installed in the same way as a painting can. Although the line between presentation and interpretation may be fine, it is in the nature of time-based media installations that they allow, as part of their identity, the possibility of a bigger gap between what the artist can specify and the realisation of the work, than in the case of a sculpture or painting. The installation is richer than its specification. If one accepts that the work is identified with its realisation and not simply its specification, this allows for a greater vulnerability to the erosion of the identity of the work through its presentation in the gallery than is the case for a conventional sculpture or painting. This vulnerability arises from the two-part nature of the creation of the time-based media installation.

Authenticity and playback

What is the relationship between the playback of the media and the idea that these works are akin, to some degree, to a performance? Authenticity in playback is very different from performance: ‘Authenticity here becomes a matter of the accuracy with which a playback device unscrambles the code representing the work, and on the accuracy with which this copy mirrors the master.’29 Time-based media installations do contain recorded media that is played back in the context of their realisation but this is not the whole story. Unlike single channel works, the identity of time-based media installations is not defined solely by their media elements.

The majority of time-based media works differ from the performance of traditional musical works in that the media element is usually pre-recorded and played back in the gallery. Time-based media installations are created as a two-part process and their realisation in the gallery includes constructing a dynamic system whereby playback and display devices render the media element into sound and picture. The transformation of the media element, via the mechanical system, into sound and picture has a dynamic quality and can draw us into thinking that this aspect of time-based media installations is what links these works to performance. Davies however would call this ‘presentation’ and not performance.30 Instead, what links all installations to performance is the fact that the work has to be completed in the gallery. An element of indeterminacy is central to the idea of a work being performed, and this indeterminacy is not present in the playback of media but is present in the act of installing an installation.

Authenticity, authorship, and control

The problem with time-based media works of art is that many aspects of their installation are under-determined and are left to the artist, installation crew, conservator and curator to determine as part of the process of realising a new installation of the work. Some artists recognise the need to think beyond a point when they can be involved in the installation of their work and strive to specify their work as ‘thickly’ as they can. Artists such as Bill Viola, Stan Douglas and James Coleman are examples of artists who ‘thickly’ specify their works. However the installation will always be richer than the specifications, and the conventions determining how this is managed when the artist is no longer involved are still being determined. Many of the artists making time-based media installations are still involved in their works. However, it is becoming clear that there is a need for individuals, within collections and museums, to learn how to install these works and pass this knowledge on. Passing on the authority to determine how a work is installed is difficult and even highly pragmatic artists such as Bruce Nauman speak of the difficulty in letting go:

After a time, you train yourself that once the work is out of the studio, it’s up to somebody else how it gets shown and where it gets shown. You can’t spend all your time being responsible for how the work goes out in the world, so you do have to let go. What happens is that it starts to become overbearing and I catch myself getting frustrated and angry about the situation. Then I see that it’s taken over and then I can let go.31

Some artists have chosen to embrace the interpretative role of those responsible for the detail of the second phase of the work’s creation. For example, Andrea Zittel has included in her installation manual for A-Z Comfort Units with Special Comfort Features by Dave Stewart (1994–5) instructions that require the curator to make decisions in installing the work that ‘make them feel comfortable’. Different artists differ in their relationship to the process by which their work is created and an important element of this pivots around the relationship to the installation phase. The relationship of the artist with this aspect of the process determines where their work lies on the continuum between sculpture and performance.

Authenticity in this context means an obligation for the museum or custodian to faithfully realise those aspects of the work which are important to its meaning. In the fullest sense this includes historical accuracy, although in a fine art context aesthetic concerns will take priority over the historical. It is possible for two performances or installations of a work to differ but both be authentic. Only if a composer’s or artist’s instructions determined every aspect of an installation would there be only one possible way in which an authentic performance or installation could be rendered. But in such cases the element of performance would be diminished. They would be more akin to painting and sculpture because their realisation would not be a two-part creative process but would rather be like decoding a recording – a mechanical process.

It seems that for a work to be like a performance, to any degree, it needs to specify something that is important to the identity of the work, for which there is an element of indeterminacy in its realisation. For example, the installation instructions might say that the space should be dark and have a theatrical feel, or that the audio levels should be high enough so people can hear it easily two feet away, or that the audio should be loud enough to grab the attention of the audience away from the images. These are all elements that require skill in interpreting what is often referred to as ‘the artist’s intent’.

The ‘work-defining’ properties of a time-based media work of art

The kinds of things that might act as work-defining properties of a time-based media installation are: plans and specifications demarcating the parameters of possible change, display equipment, acoustic and aural properties, light levels, the way the public encounters the work and the means by which the time-base media element is played back. The artist might explicitly provide work-defining instructions to the museum or designate a model installation from which the key properties of the work can be gleaned. Documentation in this context, whether it be photographs, interviews, light and sound readings or plans, represent an attempt to capture the work-defining properties.

Indeterminacy and the museum

In seeking to articulate and uncover these work-defining properties, are conservators undermining the interpretative aspect of these works or are they aiding artists to communicate their specifications? It is important to be aware of the degree to which conservation operates with the idea of a work of art developed in the eighteenth century and to resist the temptation to impose a degree of formalisation on works for which this is inappropriate. In some cases formalisation occurs when a work enters the museum because the museum offers opportunities to the artist to realise their work in a way that may not have been possible in other settings. Here formalisation is more a matter of optimising the work than falsely constraining it.

The following extract is from an interview with the artist Sam Taylor-Wood where she is discussing the installation of her work Killing Time 1994 at Tate Britain in 2003. This interview provides a snapshot of the relationship of the conservator and the artist and indicates the nature of these conversations, which often form part of a continuing dialogue.

Sam Taylor-Wood: I don’t like things being shown on television because I feel like you’re then dealing with the sculpture of the television itself. That’s some sort of parameter I guess. Projection just feels right because it slightly engulfs, it’s about being part of the piece. The other thing I quite like is that you’re in the middle and you’re pivoted by the piece, so you’re hearing somebody singing behind you and you’re trying to catch who’s singing to who at what point. I think that relationship is quite important to maintain and it works best with projection.

Pip Laurenson: Projection, at the moment, means we have to darken the room. There are things about theatre and not about theatre in this piece; do you feel that that’s something important about how the installation works?

SamTaylor-Wood: Originally it was shown on white walls and I didn’t paint the dark around [the images] but I prefer the darkness of the space because it defines the images a lot better. Because then when I was showing it the quality of the projections were different and so they disappeared a little bit in certain environments. I can’t remember which was the first show when I painted . black [around the images] and now we’ve gone to ‘Downpipe’ grey [Farrow and Ball paint colour 26]. It just felt right, as soon as I did it, I felt like they had an importance.

Pip Laurenson: They brought the images out?

Sam Taylor-Wood: Yes, so I’d like to keep that.

Pip Laurenson: And keep the darkened space even if projectors mean you can project in …

Sam Taylor-Wood: Yes I like the darkened space. I wouldn’t want this projected in a bright, open day lit space because I do feel like the piece is operatic and it is a bit of theatre as well even though it is mundane, day to day theatre. I like the fact that you walk into a darkened space.

Pip Laurenson: If we were going to show this work again .

Sam Taylor-Wood: I wouldn’t change it; I think this is a near perfect installation.

Pip Laurenson: OK, good. We can use it as a reference while at the same time thinking about what sort of decisions one might want to make in other spaces. I think it worked well because you could come in and have a look and we could work quite closely on getting the designs right.

Sam Taylor-Wood: Absolutely.32

Contingency and decision-making

In aiming to ensure a good installation of a time-based media work a historical notion of authenticity is not the whole story. There may be a trade-off in a particular performance or installation of a work between the fullest degree of historical authenticity and practical or aesthetic considerations. Judgment regarding what is significant depends on context when it comes to decisions about acceptable change in time-based media conservation, just as it does in more traditional conservation. For traditional conservation concepts of damage, loss and condition are dependent on the nature of the collection in which the object is contextualised. In a fine art collection, an object would be cleaned of debris and dirt whereas in an archaeological collection such cleaning would represent a significant loss of evidential value. In the case of allographic works, whether time-based media installations or musical works, each occasion a time-based media work is installed and each time a musical work is performed, decisions are revisited and sometimes re-made as to what aspects of the work are significant to its identity.

In the case of time-based media works, display equipment often represents the strongest link to the time in which the work was made and it is often difficult to determine the relationship of the display equipment to the identity of the work. This debate is in many ways similar to the debate about instrumentation and the identity of musical works. In his book Musical Works and Performances, Stephen Davies cites the example of Beethoven’s Appassionata (Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 23, Op.57):

The Steinway grand, with its metal frame and sturdy construction, easily survives its use in a performance of Beethoven’s Appassionata. When one hears that work on a period fortepiano, the impression is very different. Then it becomes easy to appreciate the stories about the rate at which Beethoven broke pianos, for it is apparent that the instrument is deliberately pushed to its limits in the sonata. It sounds as if it might be shaken to bits by the fury of the music.33

In claiming video, film, slide etc. as an artistic medium, artists too may push the limits of the technology and display devices and create an experience very different at the time in which the work was made to how it might be experienced today.

The issue of display equipment has been addressed in more detail elsewhere.34 In brief, I believe that it is possible to place both an inappropriately high and low level of significance on the association of a piece of display equipment with a time-based media work of art. The issue of authority in decisions of this sort is complex, and we have already discussed the possibility of two authentic installations that are different. Nevertheless, it is clear that certain considerations operate as candidates for criteria for such decisions and others do not.

Considerations that are appropriate to take into account are those related to the artistic appearance of the work and the meaning of the work; considerations that form part of its work-defining characteristics in its broadest sense. Subtle details of an installation can be of vital importance. Artists may have been extremely careful about the fine and practical details involved in the realisation of their works. In other cases an accidental detail can define the work. However, it is possible to be historically sensitive in our understanding of these works without losing sight of their wider artistic identity. The relationship of ‘performance means’ (instrumentation) to the identity of the work is a hotly contested topic for those concerned with issues of identity and authenticity in the performance of musical works.35 As time-based media works begin to age and obsolescence becomes an ever-present challenge, a fledgling debate is beginning concerning the relationship of display equipment and time-based media works.

Conservation’s mission and purpose revisited

Earlier in this article I quoted some definitions of the purpose of conservation as narrowly defined from different professional conservation bodies around the world. I chose them to illustrate a particular idea of the ‘original’. Having explored a very different notion of authenticity, one that involves honouring work- defining properties in the realisation of an installation, we can now ask how might we rephrase the purpose of conservation for a conservator of time-based media works?

Below are some suggestions:

- Conservation is the means by which the work-defining properties are documented, understood and maintained

- Conservation as a practice aims to preserve the identity of the work of art.

- Conservation aims to be able display the work in the future.

- Conservation enables different possible authentic installations of the work to be realised in the future.

In these statements the focus of conservation has shifted away from the purely material to reflect a similar shift in the nature of the works in our care.

A notion of authenticity based in material evidence that something is real, genuine or unique is no longer relevant to a significant portion of contemporary art. The work defining properties of a time-based media work may well be specific, separable and negotiated decisions and this seems to describe our experience of working with artists on the acquisition of these works into the museum.36 This does not render them arbitrary. Instead, it directs us to the need for a different conceptual framework to understand the conventions of authorship, identity and authenticity for works where the traditional paradigm depending on a causal link to the artist, traceable through material evidence, is no longer relevant.

How does this impact our concepts of change and loss? Authenticity in the context of musical performances is used to identify where the parameters of change are set in relation to the identity of the work of art. An inauthentic performance of a work is one where the identity of the work has been eroded. In this model authenticity and identity admit of degrees (i.e. a performance can be more or less authentic) and are measured against the designation of work defining properties.

What follows is an extract of a conversation with the artist Bruce Nauman. The discussion centres on the question of the relationship of the technology and medium of film to the identity of Nauman’s Art Makeup and his decision, when he transferred the work from film to video, to add a sound track of the film projector to the audio of the DVD.

Pip Laurenson: I know that you’ve made decisions with film for example, to have the soundtrack of the projectors [recorded onto the DVD]. Can you talk a bit about this? Do you think it works? It would be interesting to know your thoughts on this as a strategy.

Bruce Nauman: The main one it was done on was Art Makeup. I think it came up when the Walker [Minneapolis] was organising a retrospective and it was just so much easier to not have 16mm projectors and to put it on DVD. Because there’s basically no sound on that [work] other than the sound of the projector, so I thought, in that case, it was important to do that.

Pip Laurenson: Was the decision made because of the interest in the experience of the viewer? The sound being part of that?

Bruce Nauman: Yes because no sound is also different – silent projection – and because it is a reproduction of the original rather than the original, it’s an odd thing to think about. I wasn’t particularly interested in having … the projector [visible] on the DVD, that wasn’t part of the piece necessarily.

Pip Laurenson: So, in a way, the aspect that you originally experienced was only the sound because the projector was out of view?

Bruce Nauman: Yes.

Pip Laurenson: But I guess some people would know they are looking at.

Bruce Nauman: …a film rather than video.

Pip Laurenson: Would you rather it was shown on film? Does it bother you when those sorts of links get broken down? Some artists talk about authenticity in this context.

Bruce Nauman: The technology is still not that hard to come by, so you could do it that way if you wanted to. I think it’s when you’re dealing with having to maintain some technology that pretty much has gone, you have to decide whether that’s really part of the piece or if it can be changed . There’s a certain kind of precision in film that is different to video and if it’s important to maintain that then you have to pay attention to it.37

These decisions do not have absolute answers; they are questions of judgment and our responsibility is, in Nauman’s phrase, to ensure that we are paying attention. If we think that film was a work-defining property then to show this installation on video represents something of a loss. Of course, it may be that we cannot prevent the loss of some properties of a work but these should be named as losses. The work-defining properties of an artwork are specific to that work. Interviews at the time of acquisition are one of the tools by which we can determine what is important to the conservation of these works.

Conclusion

This paper has referenced the philosophy of music, in particular the work of Stephen Davies, to develop a conceptual framework against which we might not only understand notions of loss and change in the conservation of time-based media works of art but also look at ways in which we might determine what, in the identity of such works, is important to preserve.

In summary the following points are key for developing a conceptual framework for the conservation of time-based media works of art:

- Time-based media works of art are installed events and are like allographic works in that they are created in two phases.

- Their identity is defined by a cluster of work-defining properties which will include the artist’s instructions, artist approved installations intended to act as models, an understanding of the context in which they were made and the willingness and ability of those acting as custodians of the work to be sensitive in the realisation of a good installation.

- Time-based media installations allow for greater parameters of change than many more traditional objects of fine art. The degree to which the artist ‘thinly’ or ‘thickly’ specifies the work is relative to the specific work and the practice of the artist.

- Evidence of authorship is maintained by the causal link to the artist and the properties that the artist considers mandatory. There may also be other controls such as certificates or edition sizes.

In this conceptual framework the reference ‘state’ of an object has been replaced with the concept of the ‘identity’ of the work, which describes everything that must be preserved in order to avoid the loss of something of value in the work of art. Although my primary aim has been to explore a conceptual framework for the conservation of time-based media installations, I would hope that aspects of this framework will also fit with a wider range of conservation objects, leaving open the possibility of a unified broad definition of conservation. As in the field of cultural heritage, the broadening of the focus of conservation for time-based media installations allows conservation to stay relevant to the collection in our care.