Not on display

- Artist

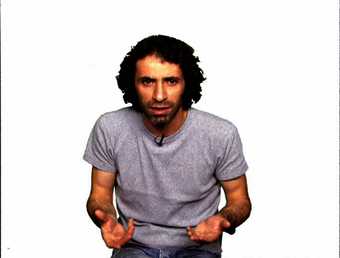

- Fikret Atay born 1974

- Medium

- Video, projection, colour and sound (stereo)

- Dimensions

- Overall display dimensions variable

duration: 10 min, 52 sec - Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the 2003 Outset Frieze Acquisitions Fund for Tate 2003

- Reference

- T11808

Summary

Fikret Atay born 1974

Rebels of the Dance

2002

Video

installation

Purchased with funds provided by the Frieze Art Fair Fund 2003

T11808

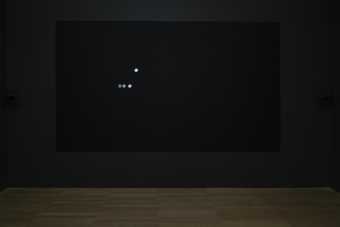

Rebels of the Dance is a single-screen video installation produced in an edition of six plus two artist’s proofs; Tate’s copy is second in the edition. The video, just under eleven minutes long, shows two boys singing and dancing in a small lobby housing a cash point or automated teller machine (ATM). The footage was taken with a hand-held camera in real time in three almost contiguous takes. At the beginning of the video the camera focuses on the cash machine before panning around to the entrance of the lobby. Two casually dressed youths come into the lobby, watched by friends who remain outside. The taller boy wears faded jeans and a black jacket over his patterned jumper. His friend is dressed in a blue hooded jacket and khaki trousers. They walk across the room and squat on the floor in front of a radiator. Looking to the camera for a prompt, they begin singing wordlessly. The melodies are traditional festive Kurdish dance music. The boys sing in harmony, following each other’s leads as they shift from one rhythmic tune to another. After a few minutes, the shorter boy stands up. He walks around the lobby, plays with the cash machine, then self-consciously starts jigging to the music. He beckons to his friend to join him and the two boys walk around the room, the shorter boy occasionally breaking into dance, raising his hands and stamping his feet. The shyer boy claps his hands and taps his feet in time with the music.

The boy in the blue jacket is evidently the more outgoing of the two, although both boys are self-consciously aware of their audience: the camera and the small group of men and boys outside the glass doors of the lobby. From time to time they glance nervously in the direction of the entrance. There is a tension between the boys’ awareness of being watched and their obvious enjoyment in expressing themselves in song and dance. Sometimes they playfully sing to one another, caught up in the moment. At other times they appear to direct their song to the cash machine. Towards the end of the video the shorter boy introduces a lyrical refrain to the music; as he dances he repeats the lines ‘Who is the pasha? Who is the groom?’ in Kurdish. The video ends with the two boys retiring out of sight while the camera focuses again on the cash machine.

The video was filmed in Atay’s home town of Batman in the Kudish region of Turkey close to the Iraqi border. Batman lies in an ancient region of southeastern Anatolia; its modern history has been dominated by oil production. Years of political oppression and military intervention have left the city devastated and poverty-stricken. Atay has described the conditions he faces making work in Batman, saying, ‘I live in a town where it is practically impossible to produce art ... To penetrate daily life, to find the depth of the time in the moment, to reflect this in the town in which one lives and to struggle for understanding... these are the difficulties faced in producing art in this town’ (quoted in Poetic Justice, p.72). Atay’s videos are improvised quickly, often with borrowed equipment. Restrictions of time and finances mean that he and his collaborators have no time to rehearse. The informal, spontaneous quality of his videos is the result of these constraints.

Rebels of the Dance

suggests the redemptive potential of creativity and performance to transform everyday existence. The video also charts the uneasy conjunction of ancient and modern in a town like Batman. The boys adapt ancient, localised rituals to the global contemporary setting of a cash point lobby. Kurdish communities, long oppressed, have relied on music to communicate cultural traditions and political dissent. In Turkey, Kurdish music was banned for much of the twentieth century, lending the boys’ improvised concert a quality of rebellion more dangerous than the teenage prank it might appear to Western eyes.

Further reading:

Dan Cameron, ed., Poetic Justice: 8th International Istanbul Biennial, exhibition catalogue, Istanbul, 2003, reproduced p.73 in colour.

Vasif Kortun, Undesire, exhibition brochure, Apexart, New York, 2003, reproduced in colour.

Adrian Searle, ‘Lost in translation’, Guardian, 16 March 2004, www.guardian.co.uk/arts/critic/feature/0,1169,1170190,00.html.

Rachel Taylor

June 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- exhilaration(50)

- hope(71)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- photographic(4,673)

- universal concepts(6,387)

-

- contrast(176)

- public and municipal(956)

-

- bank(1)

- music and entertainment(2,331)

- actions: expressive(2,622)

-

- clapping(7)

- arm / arms raised(839)

- looking / watching(581)

- boy(1,153)

- Kurdish(2)

- government and politics(3,355)

-

- revolutionary(178)

- cultural identity(7,943)

- Turkish(73)

- persecution(89)

- prejudice(79)

- race(381)

You might like

-

Mona Hatoum Measures of Distance

1988 -

Sam Taylor-Johnson OBE Brontosaurus

1995 -

Tracey Emin Tracey Emin C.V. Cunt Vernacular

1997 -

Shirin Neshat Soliloquy

1999 -

Yael Bartana Kings of the Hill

2003 -

Catherine Sullivan The Chittendens: The Resuscitation of Uplifting

2005 -

Cao Fei Whose Utopia?

2006 -

Simon Martin Carlton

2006 -

Victor Alimpiev Sweet Nightingale

2005 -

Akram Zaatari This Day

2003 -

Carey Young Product Recall

2007 -

Rabih Mroué On Three Posters

2004 -

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster Noreturn

2009 -

Akram Zaatari Dance to the End of Love

2011 -

Lala Rukh Rupak

2016