It is part of Tate’s responsibility as collector and steward of artworks that generate archival material that this aspect of the artwork is managed effectively. This responsibility is asserted through the moral rights of the artist. Before we carried out this research, the archival material generated by such works was sitting outside of structures and systems for managing collection items and was therefore at risk. The proposal plots the key challenges to doing this work and makes recommendations for the collection and stewardship of these archives. It addresses existing archival definitions, while situating the research within the framework of critical archival studies.1

This work is ongoing and unfolding. It will be tested on a case-by-case, artwork-by-artwork basis and the proposal will be revised and updated accordingly as part of Tate’s internal processes. This version has been published to accompany the other research outputs arising from the case study. Its aim is to make transparent Tate’s processes, practices and thinking around this subject, and to present the initial plans for the ongoing care and collection of artworks that generate archival material. At the end of the text is an outline of the six Tate collection works identified thus far as being those that generate archives. It describes the types of archival material generated by each of these works and offers initial guidelines for their care and stewardship.

The proposal was authored by Sarah Haylett, Archives and Records Management Researcher at Tate, with support, input and revisions by the following colleagues in Tate’s Collection Care department:

- Deborah Cane, Conservation Manager, Sculpture and Installation Art

- Adrian Glew, Archivist

- Stephen Huyton, Collection Registrar for Research

- Jane Kennedy, Records Manager

- Pip Laurenson, Head of Collection Care Research

- Louise Lawson, Head of Conservation

- Jacqueline Moon, Conservation Manager, Paper and Photographs

- Alyson Rolington, Head of Collection Management

- Kit Webb, Reshaping the Collectible Research Manager

Definition of ‘artworks that generate archival material’

Artworks that generative archival material are those that, on the instruction of the artist, or by processes that are inherent to the way the artwork exists, generate additional – usually documentary – material at each activation or display.2 The artwork creates ‘documents’ intentionally, leaving traces or remains. The generative archive material contextualises the artwork and roots it in the history of its production, exhibition, display and – in some cases – audience interaction. Artworks may be acquired with generated archival material from previous exhibitions and activations. The archival material is typically understood to be a component of the artwork; an output of the way it works, the way it functions – for example, Richard Bell’s installation Embassy (2013–ongoing) is a space for programming talks and events which are recorded and added to the archive at each activation. The generated archival material should be made available for research purposes. Unless stated by the artist, the archival material should not be used in place of the artwork when exhibited.

Other archival material at Tate

Artworks may also be acquired with three further types of material: ‘preparatory’, ‘documentary’ and ‘published’. Preparatory materials are by-products, created during the process or production of – but not forming part of – the final artwork. These include items such as sketches, photographs and maquettes. These materials are considered archival and if acquired alongside an artwork would be directed to the Tate Archive. Documentary materials include records produced during the care and stewardship of the artwork, such as images of the work in situ, interpretation, press releases and conservation documentation. This material is also collected by commercial galleries or artists’ studios and may be included upon acquisition. While documentary materials can be similar to generative archival materials, if the artist has neither the intention of making this material available for scholarly research, nor is it connected to the intention of the artwork, it is classified as documentary rather than generative and absorbed into the conservation documentation as an institutional record. Finally, ‘published’ material comprises catalogues, monographs, journals, printed ephemera, and artists’ books and serials. This material would be directed to Tate Library upon acquisition.

In considering the types of archives, records and other material held at Tate, the following typology was produced. It indicates the four different material types, which part of the Tate collection they are held in, who is responsible for them and how they can be consulted:

Proposal for artworks that generate archival material

Via a series of internal meetings with key stakeholders across Tate, it has been agreed that generative archival material is a component of the artwork and not a public record, and that the generated material will not enter the Tate Archive as it does not currently fit the collecting remit of the archive. Therefore, the archival material generated by an artwork will be collected and cared for by the Time-Based Media Conservation team, with input from the Sculpture and Paper Conservation teams where necessary. To date, the artworks that generate archival material in this way have been time-based media artworks, many of which have a performance element.

A series of questions that identify artworks that generate archival material have been added to the pre-acquisition checklist, a document used by the Collection Care Division when a work is being considered for the Tate collection. The intention is to flag these artworks early in the process so that the appropriate questions can be asked of the artist regarding any archival material acquired with the artwork, with input from the archive and relevant conservation teams.

A document that outlines Tate’s different archival practices and definitions was created in tandem with this proposal and will be incorporated into the Acquisitions Guidance for curators.3

Key principles

Tate’s work with generative artworks and their archival materials will be governed by the following four principles:

- These are artworks that, on the instruction of the artist, generate additional material at each activation or display, which situates the work within its own history of display, activation and interaction.

- The instruction to generate an archive is artist-led but collating the material during the activation or production of the artwork is the responsibility of Tate as the owner of the work.

- This archival material is a component of the artwork and (in most cases) cannot be exhibited in place of the artwork but should be made available for research.

- The material can exist as born-digital archival material and as physical archival material.

Challenges

The three main challenges that artworks that generate archival material pose to Tate are in determining:

- Who is responsible for producing and managing the archival material.

- Where the archival material sits within Tate.

- How the material can be accessed, both internally and externally.

After much internal consultation it has been agreed that these three challenges will be addressed in the following ways:

- Conservators and registrars, with curatorial input during acquisition, will hold the responsibility for the stewardship of these archives with the support of an archival worker (whose activities are outlined below).4

- The archival material – either physical or digital – will be documented and managed as a component of the artwork. The material will be managed and catalogued preliminarily through The Museum System (TMS), Tate’s collection management system, until such a time when a separate collection management system – possibly with more archival, participatory and collaborative functionality – can or needs to be sought. This should remain under review.

- Within TMS, a new component named ‘generated archival material’ will be created. Existing component management conventions will be employed. The component description field will provide a summary of the component’s archival content.

- A new component will be created for each collection of generated archival material, for ease of tracking material, with material listed by number of files or items.

- A finding aid, acting as a catalogue of the artwork’s generated archival material, will be attached to the collection management system record as a media record and will be updated accordingly. The file will be kept with the generated archival material folder in the corresponding conservation file.

- If individual pieces of the archival material are selected for loan or display, temporary additional components will be created on TMS, as per existing component management conventions, and will be deactivated upon the material’s return.

- For artworks already in the collection, Conservation will hold discussions with the artist regarding the format, structure and content of the archive when the archives have been preliminarily gathered and catalogued. These should include a discussion about if (and how) the material can be made accessible. One potential avenue is via the Art and Artists pages on Tate’s website, using a digital access copy.5 For newly acquired artworks, these discussions should be conducted as part of the conservation artist interviews carried out during the acquisition process.

Managing the generated archival material

Artworks that generate archival material will go through several steps as they continue to exist in the art collection. These include acquisition and activation (including loans), like any other work, but in the case of generative artworks, activation will include steps to gather any and all generated archival material, which will then need to be catalogued and made available for research. Each step in this process will involve a number of procedures that are to be completed by registrars, conservators, curators and archival workers, as outlined below.

On acquisition

- The Collection Care pre-acquisition checklist is employed for each artwork that Tate acquires and now includes the following questions, as well as the requirement to flag the work to the appropriate teams (listed in brackets) for further discussion and appraisal:

- Does the acquisition include archival material? (archive)

- Is the archive part of the artwork? (archive/conservation)

- Does the display of the artwork generate archival material? (conservation)

- Using the Collection Care pre-acquisition checklist, each artwork identified as one that may generate an archive should be noted clearly on the collection management system with a flag (or other similar means of identifying additional requirements).

- As these works will need to be managed on a case-by-case basis, conversations with the artist will be carried out during the acquisition process to understand what material is generated, whether its status is archival (or documentation that can be absorbed into the display history of the work) and if so, how it should be accessed and by whom. The Time-Based Media Conservation team should make every effort to include an archival worker in these discussions.

- On acquisition, in addition to the standard processes associated with conservation, a digital access copy of any existing archival material included as part of the acquisition will be produced and catalogued on the collection management system.

On activation

As part of the process of displaying the work, any new archival material that has been generated should be gathered, catalogued and digitised as per the instructions of the artist by the Time-Based Media conservation team with input from an archival worker as established during acquisition discussions.

Cataloguing

In lieu of a specific cataloguing system for these archives, a finding aid should be produced for each artwork that generates archival material.6 The intention is to list the type of material that has been archived. This will be the document that is initially sent to researchers for them to consult and decide if they wish to view the archive material or not. When producing a finding aid for the material, archival cataloguing standards should be followed (for ease, should the cataloguing system be captured into an archival cataloguing system later),7 and the following information should be captured:

- Title. This should include the artist, title of work and accession number.

- Overarching description or fond level description. This should outline the overall scope and content of the collection of material, the artwork and the intention of the archive. Each collection of generated archival material will be described individually.

- Archival history. From ISAD (G) standards: record the successive transfers of ownership, responsibility and/or custody of the unit of description, and indicate those actions that have contributed to its present structure and arrangement, such as the history of the arrangement, production of contemporary finding aids, or re-use of the records for other purposes or software migrations. If desired, an admin history could also be added which should give a history of the artwork and artist. This could be taken from, or link to, the Art & Artists page for the work on the Tate website.

- Creator

- Access restrictions. These should be documented on the finding aid and should include if and what information is redacted for any purpose (such as GDPR, or data protection where the record manager should be contacted for guidance).

Each activation will generate an additional series of material. Each additional series should be catalogued as follows:

- Reference number. This should be the collection management system component number.

- Title. This should be the name, location and dates of the exhibition where the archival material was generated, as the artwork details are in the overarching title.

- Dates. This should cover the dates of the material, not the exhibition.

- Creator. As the generated archival material is considered a component of the artwork, the creator would be the artist and captured in the fond level description, but additional creators’ names (for example, those featured in a recorded talk, or curators at borrowing institutions) should also be captured here and in the description. In the instance of reconstituted archival material, the creators should be captured at file level.

- Extent. Record the number of files, folders and items, depending on the level of description. For artworks that generate archival material, file level descriptions will be enough. This groups the material together per activation but does not list the individual items.

- Description. This should be appropriate to the level, and not repeat information in the overarching description. It should be a summary of the material in both scope and content.

There may be an opportunity to undertake participatory, collaborative cataloguing for some of the generated archival material, for instance in the case of Richard Bell’s Embassy (discussed below), which allows the voices and wishes of those creating the records to be included. This would require additional guidelines.

Staffing and resources

- These artworks provide an important point of connection between conservation and archival practices. To ensure that these generated archives are treated as such, it is important that an archival worker engages with these works on acquisition and activation. The models being used to inform this research come from an emerging area of archival practice known as critical archival studies;8 therefore, it might be beneficial to collaborate with an archival worker who works regularly with artists, community archives and within a critical archival framework.

- Additional costs for gathering, digitising, cataloguing and managing this material may include:9

- Possible need to hire a freelance archival worker with relevant expertise.

- Creation of digital access copies.

Collecting generated archival material: Guidelines and examples

This section outlines the types of archival material generated by each of the six Tate artworks identified thus far. It offers preliminary guidelines in collecting and cataloguing this archival material. As outlined above, access to the material and any next steps will be discussed with the artists and reviewed on a case-by-case basis, with the proposal and guidelines then being updated accordingly. The assertions being made here about these artworks, their archives and the artists’ intentions have been informed by interviews and discussions with each artist undertaken either as part of the Reshaping the Collectible project or as part of the acquisition process (as per conservation practice). As stated previously, this work is ongoing and unfolding, and will be tested on a case-by-case, artwork-by-artwork basis and revised and updated as part of Tate’s internal processes.

The obligation to collect archival material should be made very clear to any loaning institution during discussions, and previous iterations could be sent as an example. New guidelines will need to be created as and when the work is displayed at Tate, and the artist’s intention for the archive has been discussed and clarified.

Tania Bruguera, Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008 (T12989)

Fig.1

Tania Bruguera

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 2008

(El susurro de Tatlin #5)

Performance, 2 people and 2 horses

Tate T12989

© Tania Bruguera

Tatlin’s Whisper #5 is a performance work in which two horse-mounted police officers control the movement of visitors within the exhibition space using crowd control techniques. The work cannot be announced or advertised in advance so as to catch the audience and visitors unaware: they should not immediately realise that they are part of a performance. The artist’s intention for the work is that it is activated in places that have experienced civil unrest that was managed by mounted police, and that it is activated in times of political upheaval or disturbance, to evoke in the audience memories of earlier unrest.

The contract for this work stipulates that the owning institution must create an archive of documentation containing but not limited to ‘reactions on the piece, critical as well as explanatory materials and future clarifications of the instructions’ and ‘any resulting reference to the piece (texts, reviews, interviews, etc.)’10 each time the work is activated.

Archival material: Standard documentation produced during the activation of the work should be duplicated for the archive (photographs, videos, etc.). The archive should also include any and all interpretation materials produced, and reviews and any press about the artwork and exhibition. Emails between institutions (if loaning) – including between internal curators about why the work has been chosen for exhibition – are key as this speaks to the display conditions of the artwork (for instance, the requirement that it should be exhibited in locations where civil unrest has been managed by mounted police officers). The archive should also include copies of any discussions with the artist in preparation for the exhibition. The material will be mostly digital, and physical items should be photographed or scanned and added to the digital material for ease of access.

Guidelines: The obligation to collect archival material should be made very clear to any loaning institution during initial discussions, outlining the intention stated in the contract (see above). Previous iterations could be sent as an example. Emails should be saved as text files and webpages should be converted into pdfs for the archive. Screen recordings should be made of any webpages that include videos to preserve context, but video files should be included where possible.

Examples of materials sought for the archive:

- Curatorial emails: These are the initial discussion emails between curators about the artwork, why it is being requested for exhibition, and how and where it will sit within the exhibition or institution. This would include discussion with the artist and with Tate. Institutions should redact content as necessary.

- Interpretation emails: As the work cannot be announced beforehand, it is important to capture conversations about how the work is interpreted within the context of the exhibition. This would count as writing generated about the work as outlined in the contract for the work.

- Interpretation material: Including wall texts, websites, catalogues and other materials.

- Documentation: Documentation produced by the exhibiting institution during the installation, exhibition and deinstallation of the work should be included in the archive.

- Press material: Exhibiting institutions should capture any press, reviews, interviews or additional texts written about the work as a result of the exhibition.

- Social media: Institutions should select a period of time (such as the first and last day of the exhibition, or a number of days in the middle), and search ‘Tatlin’s Whisper #5’ on various social media platforms and capture the results. This could include a screen grab or web recording.

If no material can be provided, the following questions have been developed for the curators and exhibiting institution to create something for the archive:

- Why did you choose to display/activate Tania Bruguera’s Tatlin’s Whisper #5?

- Can you say anything about the political climate at the time and if it had any relationship to the work in the context of its display/activation?

- What, if any, interpretation material was produced for the work, and why?

Stephen Willats, ‘The Lunch Triangle’: Pilot work B. Codes and Parameters 1974 (T13339)

Fig.2

Stephen Willats

‘The Lunch Triangle’: Pilot work B. Codes and Parameters 1974

2 photographs, gelatin silver prints on paper, gouache, typed text and ink on card, printed papers, pencil and string with clipboard

Dimensions unconfirmed, each: 762 × 508 mm

Tate T13339

© Stephen Willats

‘The Lunch Triangle’: Pilot Work B. Codes and Parameters consists of three panels of images and texts with a questionnaire for the viewer. Willats draws the audience into the work by asking them to speculate on the social relation of the lunch participants in the images. In asking viewers to create the meaning of the work themselves, ‘The Lunch Triangle’ builds on Willats’s practice of art as a model for social investigation.

This artwork includes a questionnaire on which the audience can write their thoughts about the artwork, and these sheets are kept after each display of the work.

Archival material: Questionnaires printed and displayed on the clipboard as part of the display. The material will be physical.

Guidelines: Completed questionnaires should be retained as part of the artwork and returned to Tate if the work has been loaned.

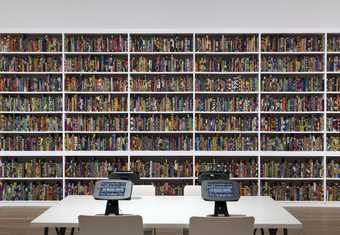

Yinka Shonibare, The British Library 2014 (T15250)

Fig.3

Yinka Shonibare

The British Library 2014

6,328 books, Dutch wax print fabric, gold foil, software, networked, world wide web, table and chairs

Overall display dimensions variable

Tate T15250

© Yinka Shonibare. Co-commissioned by HOUSE 2014 and Brighton Festival. Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

The British Library is an installation of 6,328 books wrapped in Dutch wax print fabric, of which 2,700 have names printed on their spines. The majority of the names are those of first- or second-generation British immigrants who have made a contribution to British history and culture, but the names of individuals who have opposed immigration also appear. The artwork includes a website that can be accessed in the galleries or online and which invites audiences to submit their own experiences of immigration; a selection of these submissions is then made available on the website for the duration of the display. The submissions are archived each time the artwork is displayed, creating a rich time capsule that documents the political atmosphere in which the work was exhibited and contextualises the work within Britain’s ongoing, unfolding history.

The work’s archive comprises the audience submissions to the website. The submissions are contained in a specially created inbox that is managed by Time-Based Media Conservation.

Archival material: An inbox of submissions gathered via the artwork website and the iPads on display. The material will be digital.

Guidelines: Tate is responsible for the management of the inbox where website and iPad submissions are directed. This is the case when the artwork is on loan, as well as when it is displayed at Tate. Loaning institutions should be made aware that this artwork generates archival material. Emails should be captured into text files at the end of each cycle of display and organised by date of submission and email address. Identifying information should remain as part of GDPR rules should someone contact Tate to have their entry removed but will need to be redacted as and when the material is made available to researchers. There should be two files, one containing submissions and one containing redacted, ‘research’ submissions.

Pawel Althamer, Film 2000 (T12404)

Fig.4

Pawel Althamer

Film 2000, still from the trailer for the 2007 iteration in London’s Borough Market featuring actor Jude Law

Performance, film, drawings, storyboards and photographs

Display dimensions variable

Tate T12404

Film encompasses both a ninety-second trailer and a thirty-minute performance. The trailer is made and shown in cinemas in anticipation of the performance. It invites the audience to witness a well-known actor enacting half an hour of daily life in an iconic location. Releasing the trailer in this way allows the work to blur the boundaries between cinema and real life. The work has been performed four times: in Ljubljana (2000), Pittsburgh (2004), Warsaw (2005) and London (2007).

Each time the work is reactivated, it generates a body of preparatory material (sketches, storyboards, photographs and props). The artist refers to this material as archival.

Archival material: This is all preparatory material produced during the making of the trailer. The acquisition included the archives of the four previous iterations. The material will be physical and digital and may include props.

Guidelines: The obligation to collect archival material should be made very clear to any loaning institution during discussions. Material should be gathered throughout the period of production by those making the trailer and sent to Tate at the end. It should include scripts, notes, storyboards, photographs and physical objects. For instance, the archival material from the London iteration of the work curated by Tate in 2007 includes a red hat worn by one of the actors during the performance.

Oswaldo Maciá, Something Going On Above My Head 1999 (T13319)

Fig.5

Oswaldo Maciá

Something Going On Above My Head 1999

Audio, 16 channels, megaphone speakers, wall diagram and paper leaflets

30 min

Overall display dimensions variable

Tate T13319

© Oswaldo Maciá

Something Going On Above My Head is a sound installation featuring a symphony of over two thousand types of birdsong, which the artist gathered from ornithological archives and audio libraries across the world. Each installation includes a leaflet designed by the artist showing the layout of an orchestra but with the instruments accompanied by the names of birds. In the most recent activation at Tate Modern in 2021, the artist decided against printing a leaflet due to sustainability concerns, and hand-painted the mural on the gallery wall. The artwork was acquired with a metal box of material including leaflets from previous displays, preparatory material and documentation.

Archival material: As outlined, the archive acquired with the artwork includes preparatory material, leaflets from previous iterations and documentation from previous displays (such as gallery floor plans and images of the installation). The material will be physical and digital.

Guidelines: The obligation to collect archival material should be made very clear to any loaning institution during discussions, and previous iterations could be sent as an example. The leaflet should be collected alongside any preparatory material and correspondence with the artist and his studio about the design of the leaflet and the overall installation. Catalogues for the exhibition should be included, alongside documentation of the installation.

Richard Bell, Embassy 2013 (acquisition candidate)

Fig.6

Richard Bell

Embassy 2013

Canvas tent with annex, aluminium frame, rope, synthetic polymer paint on ply; 16 mm film transferred to single-channel digital video, black and white, sound; archive

Installed: 3050 x 6000 x 7930 mm; four sign boards: 600 x 1800 x 25 mm, 900 x 1240 x 30 mm, 900 x 900 x 50 mm, 1800 x 1200 x 25 mm; 1 hr, 11 min, 42 sec

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney and Tate

Image courtesy the artist and MCA, © Richard Bell. Photograph: Daniel Boud

Embassy is a joint acquisition between Tate and the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Sydney. The work comprises a military-style tent, a banner and a series of protest placards. It evokes the Aboriginal Tent Embassy that was set up in Canberra in 1972 and which has been maintained ever since as part of the campaign for the political and land rights of Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islander people. The space inside the tent is used as a public forum to host performances, dialogues, workshops and screenings by local activist groups. The artist requests that any documentation produced be a collaborative endeavour and that the voices of those activating the tent are represented in the archive.

Material generated during this programming is archived as part of the work. The archive material can be used in future activations.

Archival material: At present, this archive duplicates some standard conservation documentation such as photographs of the artwork in situ, but it should also include recordings of events and talks programmed as part of the activation. There is the potential for this archive to expand to also include material produced by those activating the tent. The material will likely be digital.

Guidelines: The obligation to collect archival material should be made very clear to any loaning institution during discussions. Previous iterations could be sent as an example. There is the potential to utilise a participatory and collaborative community archiving approach that will include the voices and perspectives of the activists and record creators in the archiving processes. This will require further research and additional guidelines and is being discussed with the artist.