In Tate Modern

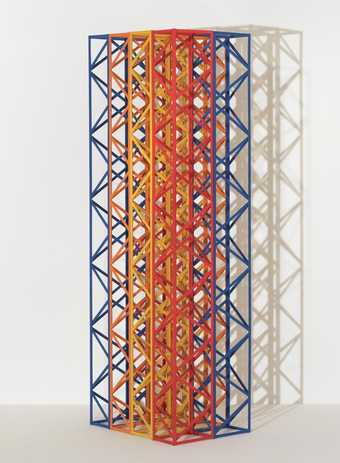

- Artist

- Rasheed Araeen born 1935

- Medium

- Wood, paint and metal

- Dimensions

- Display dimensions: 1828 × 2438 × 140 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 2007

- Reference

- T12408

Summary

3Y + 3B is a large, horizontally oriented painted wooden sculpture by the British-Pakistani artist Rasheed Araeen. The work is composed of six rectangular wooden lattice framework structures, three painted yellow and the other three blue, which are arranged vertically and screwed onto a sheet of hardboard. The hardboard is painted and divided into two halves – the left side, on which the three yellow lattice structures are mounted, is painted blue, and the right side, onto which the three blue framework structures are affixed, is painted yellow. The sculpture hangs from the wall by a series of mirror plates attached to its reverse.

Trained as a civil engineer in Karachi, Pakistan, Araeen moved to the UK in 1964, and he made 3Y + 3B four years after this move, when he was living in London. Supporting himself financially by working as an engineering assistant for British Petroleum, Araeen had no formal education in sculpture. The lattice structure employed by Araeen in 3Y + 3B and other works such as Rang Baranga 1969 (Tate T12409) displays a clear connection to the artist’s engineering background, but it has also been compared by the art historian Paul Overy to the repeated geometric patterns found in Islamic art and architecture in Araeen’s native Pakistan (see Overy 1994, p.7). However, the artist has stated that his use of the lattice relates not only to architectural and engineering structures, but makes reference to forms in early twentieth-century modernist art – Russian Constructivism and Dutch De Stijl in particular – and the utopian ideologies that accompanied those movements (see Overy 1994, p.7).

As the artist explained to Tate curator Andrew Wilson in 2008, ‘The title of the work 3Y + 3B is a reference to three yellows and then three blues’ (Araeen 2008, accessed 6 May 2015). The art critic and historian Patricia Bickers has argued that Araeen’s use of contrasting colours in this and his other works, along with his employment of coloured and bicoloured backgrounds, creates a sense of movement in the works that is not present in the largely monochromatic sculptures of Araeen’s minimalist contemporaries, such as Sol LeWitt and Robert Morris (see, for instance, Sol LeWitt, Two Open Modular Cubes/Half-Off 1972, Tate T01865, and Robert Morris, Untitled 1965, reconstructed 1971, Tate T01532). As Bickers observes:

In the majority of [Araeen’s] reliefs, pairs of contrasting colours were used such as red/blue, blue/yellow, whose values, being exactly equal, create the optical illusion that the structures themselves ‘jump’, confusing the relationship between figure and ground so that neither dominates.

(Bickers 1988, unpaginated.)

Furthermore, the art critic Jean Fisher has noted of Araeen’s lattice reliefs that ‘the diagonals formed an internal spiral which seemed to ripple as the spectator walked back and forth in front of it’ (Fisher in Minimalism and Beyond: Rasheed Araeen at Tate Britain, exhibition catalogue, Tate Britain, London 2007, p.4.)

3Y + 3B formed part of the retrospective exhibition Minimalism and Beyond: Rasheed Araeen at Tate Britain, which was held from April to August 2007 at Tate Britain, London. In the exhibition’s catalogue, the curator Andreas Leventis identified Araeen as a ‘pioneer of Minimalist sculpture in Britain’, but one whose contribution had until that point remained largely unrecognised (Leventis in Tate Britain 2007, p.1). When Araeen visited the influential exhibition The Art of the Real at the Tate Gallery in 1969, which had travelled from the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and featured the work of American minimalist sculptors such as Morris and Donald Judd, he was already producing his own experiments in minimalist form, such as 3Y + 3B. Yet Araeen’s work has often been discussed in art historical studies in relation to postcolonialism rather than minimalism. This is partly due to the near-invisibility of black and Asian artists within twentieth-century Western art history and visual culture and the fact that Araeen produced increasingly political work during the 1970s and 1980s as a means of addressing this lack of visibility.

Further reading

Patricia Bickers, ‘From Object to Subject’, in From Modernism to Postmodernism, Rasheed Araeen, A Retrospective: 1959–1987, exhibition catalogue, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham 1988, unpaginated.

Paul Overy, ‘The New Works of Rasheed Araeen’, in Rasheed Araeen, exhibition catalogue, South London Gallery, London 1994, pp.5–20.

Rasheed Araeen, ‘Rasheed Araeen: 3Y + 3B’, interview with Andrew Wilson and Melanie Rolfe, Tate Research, London, 9 July 2008, http://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/rasheed-araeen-3y-3b, accessed 6 May 2015.

Judith Wilkinson

May 2015

Supported by Christie’s.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- non-representational(6,161)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- pattern(358)

- repetition(391)

- symmetry(220)

You might like

-

Nalini Malani Untitled I

1970/2017 -

Nalini Malani Untitled II

1970/2017 -

Nalini Malani Untitled III

1970/2017 -

Rasheed Araeen Bismullah

1988 -

Rasheed Araeen Rang Baranga

1969 -

Rasheed Araeen Zero to Infinity

1968–2007 -

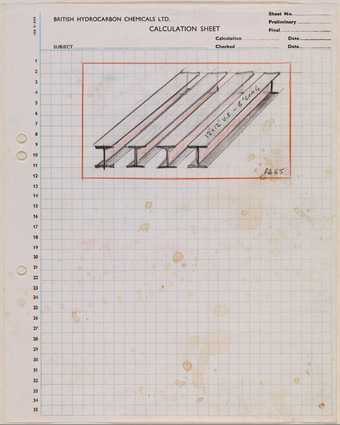

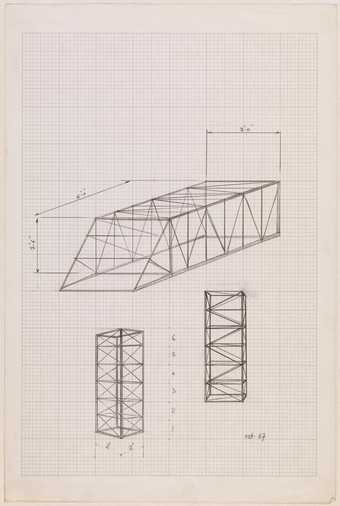

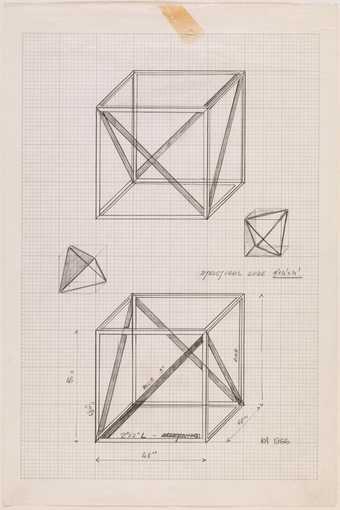

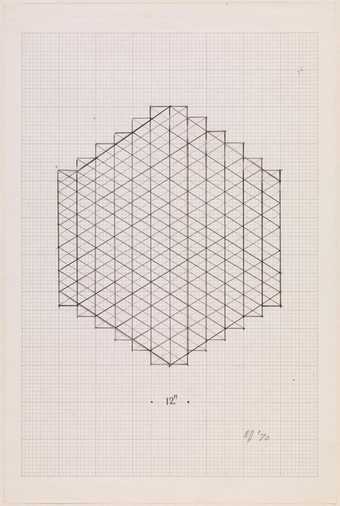

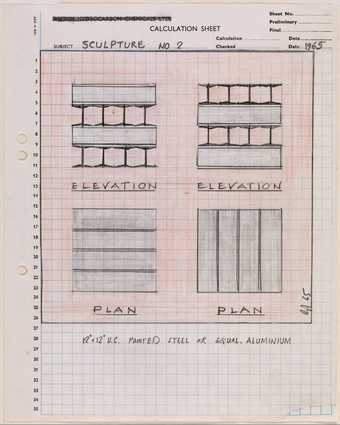

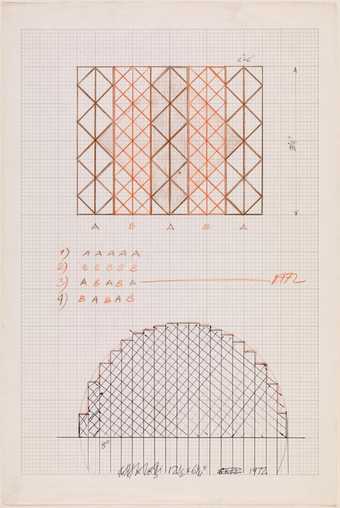

Rasheed Araeen Drawing for Sculpture

1965 -

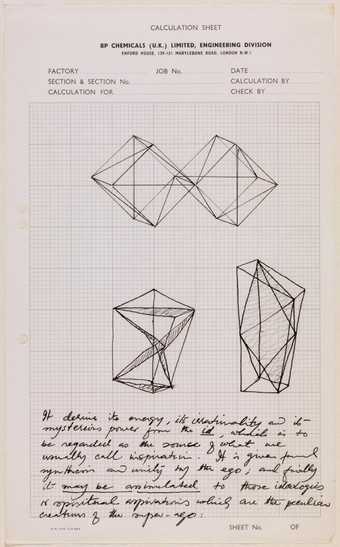

Rasheed Araeen Drawing for Sculpture

1968 -

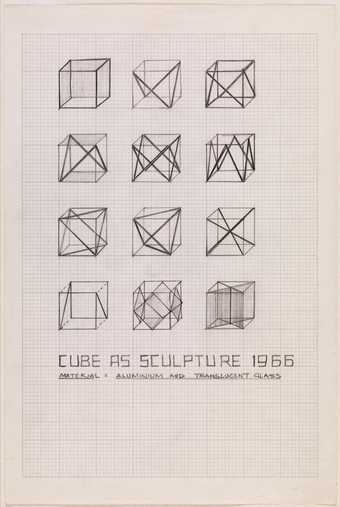

Rasheed Araeen Drawing for Sculpture

1966 -

Rasheed Araeen Drawing for Sculpture

1967 -

Rasheed Araeen Drawing for Sculpture

1966 -

Rasheed Araeen Drawing for Sculpture

1970 -

Rasheed Araeen Drawing for Sculpture

1965 -

Rasheed Araeen Drawing for Sculpture

1972 -

Rasheed Araeen Lovers

1968