In Tate Modern

- Artist

- Carl Andre born 1935

- Medium

- Pine

- Dimensions

- Object: 2140 × 156 × 156 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased 1972

- Reference

- T01533

Summary

Last Ladder 1959 is an early wooden sculpture by American minimalist artist Carl Andre. It is made from a tall, thin beam of reclaimed timber, into which five hollows are carved. These hollows are almost identical in width and height, but the configuration of the indents themselves alternates between hollows with a flat plane at the bottom and a curve at the top, and hollows with a curve at the bottom and a flat plane on top, giving an undulating, wave-like appearance to the channel of vertical concaves engraved in the wood.

The beam from which Andre made Last Ladder was found on a New York construction site by his two close friends – the painter Frank Stella and avant-garde filmmaker Hollis Frampton – and brought back to Stella’s studio, where Andre began work on it. Laying it horizontally, he used 3.8 cm chisels to carve the hollows in the wood. Apart from these hollows the beam was left in its found state, and as such it bears the marks of its use as a building material. A crooked, rusted nail sticks out from the left hand side of its temple and a series of large, drilled holes line the sides of the work, piercing through the width of the wooden beam. The work’s surface is covered in cracks, with one particularly large split running down its right hand side. Its edges are scuffed and the wood’s surface has a natural patina, almost completely black in areas toward the base, that hints at its industrial past life.

Unlike its smaller counterpart, the carved wooden sculpture First Ladder 1958 – made by Andre in New York a year earlier and set into a wooden block to give it stability – Last Ladder does not have a base, but stands upright on its own, though somewhat unsteadily. First Ladder and Last Ladder were the only Ladder works made by Andre and were originally titled Ladder No. 1 and Ladder No. 2 respectively. Although both sculptures have markings that resemble footholds, like all of Andre’s sculpture they have no practical purpose and neither is fit for use as an actual ladder. Rather, the titles serve to emphasise the unusable nature of Andre’s art objects, while affirming their relation to the human body. At just over two meters high, Last Ladder towers precariously over most viewer, its stature, proportions and unsupported verticality giving it an anthropomorphic quality.

During the late 1950s Andre mainly worked in wood, a material with which he has continued to experiment throughout his career and which he has called ‘the mother of matter’, owing to its timeless quality and its origins in nature (Andre 2000, p.2). Last Ladder was his largest carving to date and its tall, vertical form was directly inspired by sculptor Constantin Brancusi’s (1876–1957) series of Endless Columns, the repeated hollows and alternating pattern cut into Last Ladder paying homage to the carved, truncated pyramids and the simple, repeated motif that make up Brancusi’s largest Endless Column, completed in 1938 and located in Târgu Jiu, Romania. As critic David Bourdon has stated, Andre looked to Brancusi because the European artist was ‘unexcelled in essentialising forms’, a quality which, at the time, appealed to Andre’s developing minimalist sensibilities (Bourdon 1978, p.18).

Last Ladder was Andre’s last carved wood piece and proved to be a significant turning point in his career. Soon after it was made in 1959, Stella commented to Andre that the untouched, uncarved back surface of the wooden beam was sculpture too. Hearing this, Andre had a revelation about his own practice, realising that: ‘the wood was better before I cut it than after. I did not improve it in any way’ (quoted in Bourdon 1978, p.19). From this point onwards, although he continued to work with wood, his sculptures were modular constructions made from square or rectangular wooden blocks, rather than carved single pieces. Talking about this change in his approach to making, Andre has said:

Up to a certain time I was cutting into things. Then I realized that the thing I was cutting was the cut. Rather than cut into the material, I now use the material as the cut in space.

(Quoted in Bourdon 1978, p.19.)

In contrast to Andre’s later works, Last Ladder and the other carved wood sculptures of this early period are distinct in their demonstration of the artist’s hand and in their evidently autonomous nature as artworks. Whereas later wood works, including Cedar Piece 1959/1964 and Secant 1977, are not cut into or drastically altered but rather are arranged by the artist, these early sculptures stand out as singular works. As the art historian and curator R.H. Fuchs has noted: ‘They are like strong signs, heavy and robust (paying homage to the material), each of them with its own identity’ (Fuchs 2000, p.6).

The legacy of Last Ladder was the emergence of a sculptural practice far more focused on the ability of material itself to convey meaning and message to the viewer, and the highly streamlined and minimalist approach to form evident in Andre’s later work.

Further reading

David Bourdon, ‘A Redefinition of Sculpture’, in Carl Andre: Sculpture 1959–1977, New York 1978, pp.13–40.

R.H. Fuchs (ed.), Carl Andre: Wood, exhibition catalogue, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven 2000.

Paula Feldman, Alistair Rider and Karsten Schubert (eds.), About Carl Andre: Critical Texts Since 1965, London 2006.

Clare Gormley

March 2016

Supported by the Terra Foundation for American Art.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

One of Andre’s early carvings, Last Ladder was made by cutting a series of concave forms into a rough-hewn beam of wood that had been salvaged from a construction site. Andre intended his cutting to reveal the distinctive qualities of this raw material. He later said of this sculpture: ‘the wood was better before I cut it than after. I did not improve it in any way.’

Gallery label, January 2016

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

Carl Andre born 1935

T01533 Last Ladder

1959

Not inscribed

Wood, 84 1/4 x 6 1/8 x 6 1/8 (214 x 15.5 x 15.5)

Purchased from the artist through the John Weber Gallery, New York (Grant-in-Aid) 1972

Exh: Carl Andre: Sculpture 1959-78, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, March-April 1978 (1, repr.)

Lit:

Hollis Frampton, letter to Enno Develing published in exh. catalogue Carl Andre, Gemeentemuseum, The Hague, August-October 1969, pp.8-9, repr. p.15; exh. catalogue Carl Andre: Sculpture 1958-1974, Kunsthalle, Bern, April-June 1975, No. 1959-1, p.13, repr. p.12 as 'Last Ladder'

Repr: exh. catalogue Carl Andre, Guggenheim Museum, New York, October-November 1970, p.10 as 'Ladder No.2' Winter 1958-9; Burlington Magazine, CXVIII, 1976, p.765

Carl Andre told the compiler on 12 May 1972 that he shared his friend Hollis Frampton's small apartment in Mulberry Street, New York, from the autumn of 1958 until the spring of 1959. They were also seeing a great deal of Frank Stella, who had been to school with them (though Andre, who was in a different class, did not get to know him until after they had left), and in 1959 Andre wrote a statement for Stella for the catalogue of the Museum of Modern Art's Sixteen Americans

exhibition.

At this period Andre was making drawings and sculptures, and writing. He had the idea of negative sculpture, taking a volume and cutting into it, as a kind of reaction to Brancusi. Hollis Frampton had been to visit Ezra Pound, who was fascinated by sculpture and had written a small monograph on Brancusi. Through Frampton's interest in Pound and Pound's interest in Brancusi, Andre himself became interested in Brancusi's carvings, especially the 'Endless Column'; but instead of making convex forms, he wanted to do concave cutting. He made sculpture in plastic and also in wood, using wood which he could scavenge or steal from construction sites. Stella and Hollis Frampton found this piece on a construction site and carried it back for him (he thinks it is hemlock of fir). The hole at the bottom was already there. He used the same method of cutting as in 'First Ladder' and 'Baboons', with a configuration of a curve and a plane, and a curve going into a plane. He worked on it in Stella's studio and carved it horizontally, using 1 1/2 in (3.8cm) chisels. 'First Ladder', the only other work called 'Ladder', is smaller and is set into a block to give it stability, whereas this work can stand upright - though somewhat unsteadily - on its own. He said that it was his largest carving and the culmination of the first phase of his sculpture. It was not exhibited at the time and was thought to have been lost until it was rediscovered by Hollis Frampton in the possession of a friend in the autumn of 1971. (The two sculptures now known as 'First Ladder' and 'Last Ladder' were originally entitled 'Ladder No. 1' and 'Ladder No. 2' respectively; they were incorrectly numbered in the catalogue of the exhibition at The Hague the other way round).

In his account of Andre's development (loc. cit.), Hollis Frampton confirmed that 'Last Ladder' and the related large wood carvings were made in the spring of 1959. However, according to the catalogue of Andre's work prepared by Angela Westwater in collaboration with the artist (Bern, op. cit.), 'First Ladder' dates from the end of 1958. For some years certain of these early works were known only from the photographs which Frampton took of them at the time. The one of this work shows it standing in Stella's studio, with Stella's large aluminium picture 'Union Pacific' 1960 hanging on the wall behind. It still has a few traces of aluminium paint.

Published in:

Ronald Alley, Catalogue of the Tate Gallery's Collection of Modern Art other than Works by British Artists, Tate Gallery and Sotheby Parke-Bernet, London 1981, pp.9-10, reproduced p.9

Explore

- abstraction(8,615)

-

- from recognisable sources(3,634)

-

- man-made(999)

- non-representational(6,161)

-

- geometric(3,072)

- formal qualities(12,454)

-

- purity(43)

- tools and machinery(1,287)

-

- ladder(144)

You might like

-

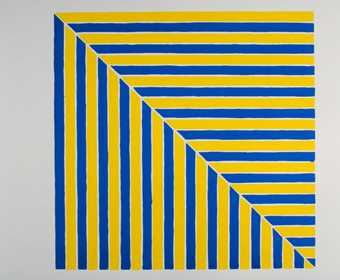

Frank Stella Untitled (Rabat)

1964 -

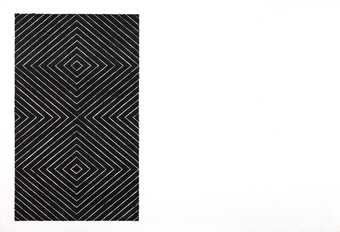

Frank Stella [title not known]

1967 -

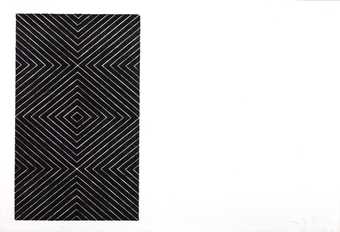

Frank Stella [title not known]

1967 -

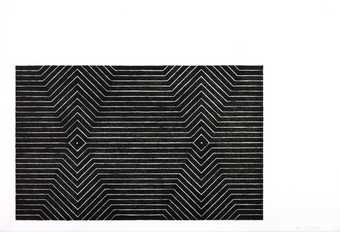

Frank Stella [title not known]

1967 -

Frank Stella [title not known]

1967 -

Frank Stella Hyena Stomp

1962 -

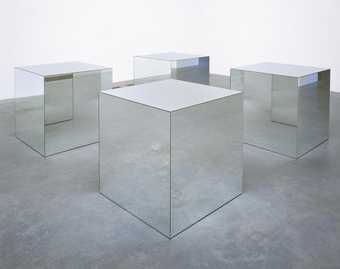

Robert Morris Untitled

1965, reconstructed 1971 -

Carl Andre Equivalent VIII

1966 -

Larry Bell Untitled

1962 -

Carl Andre 144 Magnesium Square

1969 -

Kim Lim Intervals II

1973 -

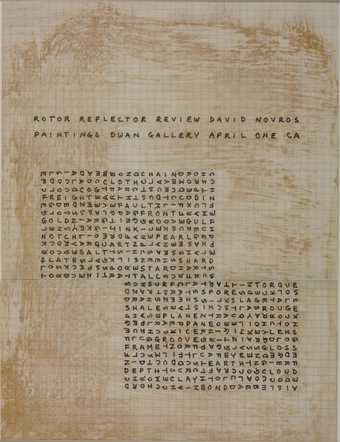

Carl Andre Rotor Reflector Review

1967 -

Carl Andre Steel Zinc Plain

1969 -

Carl Andre Venus Forge

1980 -

Richard Serra 2-2-1: To Dickie and Tina

1969, 1994