Not on display

- Artist

- George Warner Allen 1916–1988

- Medium

- Oil paint and tempera on canvas on plywood

- Dimensions

- Support: 1219 × 1219 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by Paul Delaney, executor of the artist's estate 1992

- Reference

- T06604

Summary

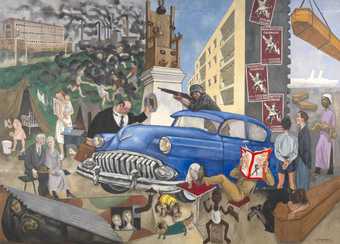

George Warner Allen's paintings of English pastoral idylls led critics, including the painter Brian Thomas, who wrote the introductory essay for Allen's 1952 exhibition at Walker's Galleries, London, to categorise him as a Neo-Romantic artist. This tendency, which included Graham Sutherland (1903-1980), John Minton (1917-1957) and John Craxton (b.1922), came to prominence during the late 1930s and continued to flourish for a brief period after the Second World War (1939-45). However, while Allen shared their idealised attitude towards nature and England, his allegiance to traditional subject matter rendered in styles and techniques stretching back to the Italian Renaissance placed him at odds with their overtly modern manner.

Picnic at Wittenham was considered by Allen to be the outstanding work of his early phase. In spite of the contemporary setting, the stylistic and compositional references to Poussin's (1594-1665) pastorals are clear; indeed, shortly after completing it, he painted its companion Et in Arcadia Ego, a homage to Poussin's painting of the same title. In Picnic at Wittenham Allen has applied glazes of thin oil paint over tempera underpainting to enhance form and colour; a technique which he particularly associated with Titian (c.1487-1576) and other Venetian painters of the High Renaissance.

The principal subject of the painting seems to be the artist's calling. In the foreground, with a bird and a squirrel beside him, the painter lies sleeping in the shade of the trees, a variation on the traditional trope of the sleeping shepherd; between him and the viewer are his paints and brush and an unfinished watercolour of the landscape beyond. In the sunlit middle distance, a group of friends are picnicking. The contrast between the relaxed social interaction of this group and the isolation of the artist is heightened by Allen's use of shade and light. Whether the picnickers are a product of the sleeping figure's imagination is not clear, but their compositional separation from him reflects Allen's belief that the artist has a special role. An equal subject of this painting, therefore, is inspiration and the primacy of instinct and intuition. In keeping with this theme, the artist is about to be wakened by the potent mythical figure of the faun, symbol of the vitality of the irrational.

Although Allen was himself a somewhat solitary man, this image of an artist is not a literal self-portrait. Wittenham, however, does refer to an actual place, namely Long Wittenham, Oxfordshire. It is near to where Allen lived, and is part of the local countryside that he would often visit to paint watercolour landscapes.

Further reading

Brian Thomas, George Warner-Allen: An Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings, Walker's Galleries, London 1952, reproduced p.1

John Christian (ed.), The Last Romantics: The Romantic Tradition in British Art, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1989, p.197

David Mellor (ed.), A Paradise Lost: The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain 1935-55, exhibition catalogue, Barbican Art Gallery, London 1987, p.143

Toby Treves

25 January 2001

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Display caption

The theme of this painting is the role of the artist. In the foreground the painter lies sleeping beside his paints and brushes and an unfinished watercolour of the landscape beyond. This artist figure may represent GW Allen, though it is not actually a self-portrait. In the middle distance a group of friends are picnicking in the sunlight. By contrast, the artist sleeps in the shade. He is shown as a figure apart, absorbed in a world of dreams and the instinctive desires represented by the faun standing over him.

Gallery label, August 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Technique and condition

Painted in tempera glazed with resinous, oil colours on a gessoed panel, the painting exemplifies the painting technique Allen developed over many years of study and experimentation. Allen described his struggle to discover an appropriate technique in an article by Sydney R. Jones 'George Warner-Allen' published in Studio no. 143, 1952. 'I read every treatise I could find, both ancient and modern, on the technique of painting, and arrived at the conclusion that the solution of my problem probably lay in some combination of the tempera and oil techniques such as the great Venetians appear to have used. Such a combination allows of great technical freedom in handling with as much elaboration as desired. The use of a short sharp impasto is a beautiful foil to the superimposed glazes in a highly resinous, fluid medium.'

The panel is constructed from a sheet of plywood reinforced at the back with a substantial timber framework. Over the front was stretched a piece of fine linen, probably glued to the face of the plywood and tacked to the sides and back of the timber framework. Two pieces of coarser linen were also adhered to the exposed plywood at the back. All surfaces were given a coat of water soluble gesso and the front face was built up in several layers of gesso, reducing the texture of the canvas.

The composition was worked out in a series of preparatory sketches before being drawn onto the panel. An underpainting in tempera covers the majority of the panel. The stiff paint used to model the forms retains all the detail of his brushwork in sharp relief. Over this light underpainting Allen has applied local colour and developed the forms in highly, resinous oil glazes. Some fine translucent glazes are worked into the textural detail, as in some areas of tree foliage. Further modification is achieved with neutral coloured glazes such as those applied to the sky, which are indistinguishable from the overall varnish layer. Allen prepared both his tempera and oil paints himself and the uneven dispersion of the pigments, leaving clusters of pigment, is clearly visible in some of the glazes.

The condition of the painting on acquisition was structurally sound although it had been visibly exposed to adverse conditions. The exposed gesso on the back and edges had been extensively attacked by rampant mould growth and the front was covered with dirt. Dirt and debris from the mould growth were removed and the painting refitted into its existing frame.

The stained, moulded wood frame with gilded details was fitted with glass to protect the delicate surface of the painting.

Roy Perry

1996

Explore

- emotions, concepts and ideas(16,416)

-

- emotions and human qualities(5,345)

-

- inspiration(36)

- isolation(290)

- eating and drinking(409)

-

- picnic(67)

- actions: processes and functions(2,161)

-

- sleeping(315)

- UK counties(19,585)

-

- Oxfordshire(1,239)

- England(19,202)

- England, South East(5,940)

- England, Southern(8,982)

- classical myths: creatures(143)

-

- satyr(28)

- arts and entertainment(7,210)

-

- artist - non-specific(2,109)

You might like

-

Peter de Francia The Bombing of Sakiet

1959 -

Jacques-Émile Blanche On the Pier at Dieppe

c.1938 -

Georges Rouault The Italian Woman

1938 -

André Minaux Arm-chair in an Interior

1951 -

Claude Venard Still Life

1955–6 -

Stanley William Hayter Ophelia

1936 -

Jean Hélion Nude with Loaves

1952 -

George Warner Allen The Return from Cythera

1985–6 -

Boris Taslitzky Riposte

1951 -

André Fougeron Atlantic Civilisation

1953 -

André Fougeron The Cock Fighters

1950 -

André Fougeron Return from the Market

1953 -

André Fougeron Massacre at Sakiet III

1958 -

Boris Taslitzky Study for ‘The Death of Danielle Casanova’

1949 -

Balthus (Balthasar Klossowski de Rola) Nude on a Chaise Longue

1950