Not on display

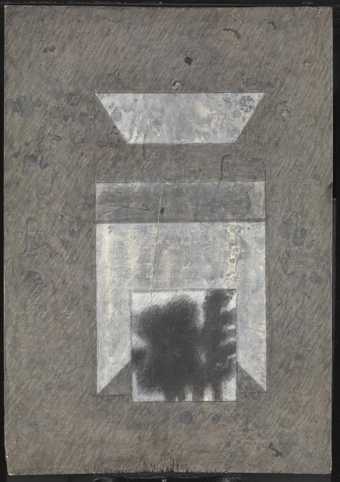

- Artist

- Zahoor ul Akhlaq 1941–1999

- Medium

- Acrylic paint on wood

- Dimensions

- Support: 318 × 226 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Purchased with funds provided by the South Asia Acquisitions Committee 2015

- Reference

- T14308

Summary

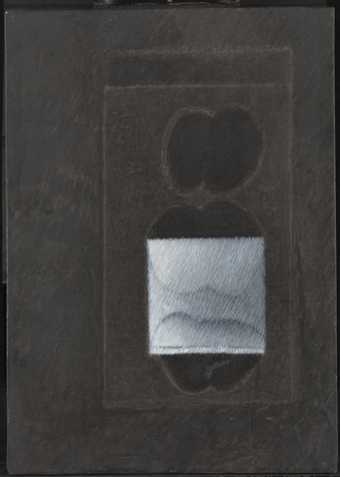

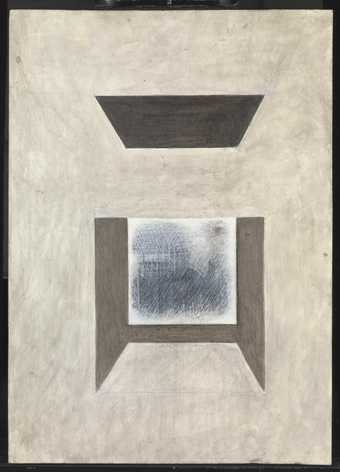

This is one of five small paintings on board in Tate’s collection by the Pakistani artist Zahoor ul Akhlaq (see Tate T14308–T14312). Dating from 1992–3, they are from a sequence of works based on the format of the takhti, a small wooden slate still used in Pakistan in rural or traditional schools for children to write on, wipe clean and reuse. Two of the five paintings – this one and Untitled (Tate T14309) – are from a series made in the early 1990s entitled Still Still Life. All five paintings were created during a period in Akhlaq’s career when he travelled extensively: having spent time at Yale University in the United States on a Fulbright Fellowship (1987–9), he taught at Bilkent University in Ankara, Turkey (1992–3) before moving to Toronto, Canada from 1993–7. Due in part to the lack of a permanent studio, he used acrylic rather than oil paint and often worked on a small scale.

The series Still Still Life, as well as drawing on the appearance of the takhti, reflects the original function of the slate as a medium for instruction in the context of an academic art education. The lesson here appears to be the study of a three-dimensional object: a basic first lesson of studio drawing or painting. These works were executed in monochromatic colours using objects with simple shapes, in this case, apples. These largely black and gray works depict either a single or repeated apple shape against a slightly lighter background, set within a frame that is a few shades lighter still. The window-like framing device within each work evokes modernist abstraction, which Akhlaq had studied in detail; the layers of gradation on the other hand were achieved using short diagonal brushstrokes derived from the pardakht feathering technique used in traditional miniature painting from Pakistan to build up layers of colour with a fine brush, and learnt through laborious discipline. Akhlaq made use of black and white photocopies in developing his paintings and was interested in disrupting the notion of the true or accurate copy so prized in traditional miniature training. In an interview in 1991 he stated, ‘Because black is the beginning – it becomes a challenge. I try not to make it easy for myself. And I become very intensely involved in the structure.’ (Quoted in Minissale 1991, p.152.) In the same interview he also explained that he ‘paints with many layers of thin paint’, as evident in this work, where the surface is finely textured with rich variations achieved through the controlled application of paint.

Historian Virginia Whiles has written of the technique employed in paintings such as this:

Such marks make the image oscillate back and forth, back into the process of miniature making and forward into a Modernist frame. The reverse gear refers to the initial stage of drawing exercises: an exquisitely laborious procedure whereby the miniature student spends hours, days and nights, simply drawing parallel lines into square inch boxes with the razor sharp point of an extra hard pencil.

(Whiles 2006, p.54.)

Akhlaq is widely credited for bringing about a radical change in the prevalent academic attitude towards the traditional arts in Pakistan, combining the late international modernist aesthetic then dominant in Lahore with the formal and material concerns and methods of Indo-Islamic miniature painting. While a student at the Royal College of Art in London in the late 1960s, he had studied the collections of Mughal miniature manuscript paintings at the Victoria and Albert Museum. This led to experimentation in drawings and on canvas with the spatial arrangement of the manuscript page in which the painted area, delineated by an illuminated border containing text, would usually depict an illustrated scene. Akhlaq subdivided his compositions so that the frame appeared slightly to the right of centre, the border wider on the left side as if it were one leaf of an opened book. Curator Nazish Ata-Ullah has described how in these works, ‘The interplay between the center [sic.] and its peripheral spaces allowed for experimentation that was visually playful and indefinite. This frame within a frame became Akhlaq’s mark in countless works over decades of practice.’ (Asia Society 2009, pp.52–3.)

Akhlaq thus employed the visual device of the window to create simultaneous flatness and depth of field, using the layout of the page border as a frame and the inner rectangle as the picture plane. The imagery references modernist abstraction, but with subjects based on the artist’s own experience combined with traditional technques. Although Akhlaq studied works by well-known modernist painters such as Mark Rothko, Frank Stella, Joseph Albers and Ad Reinhardt, he did so alongside his investigation of traditional Chinese and Japanese painting as well as Indian miniatures, deeply interested in the treatment of surface, multiple perspectives and two-dimensionality. His early work was influenced by fellow Pakistani painter Shakir Ali (1914–1975), who had returned from studying at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and introduced modernist painting to the National College of Arts in Lahore, where he was principal. Whiles has noted, ‘A keen Modernist but conscious of the post-colonial predicament, like any South Asian artist, Akhlaq was seeking ways to localize his Modernism.’ (Whiles 2006, p.54.) She continues:

Akhlaq’s reinvention of the miniature was essentially anarchic in its refusal to toe the nationalist line. Ironically the process of the ‘vulgarization’ and the commodification of the miniature in the Zia years may well have contributed towards Akhlaq’s realization of the potential play offered by the miniature medium … He discovered a force of invention in the miniatures, which he had simply not realized before. To juxtapose material from his own cultural history with contemporary innovations proposed a fresh vocabulary for his painting.

(Whiles 2006, p.30.)

Further reading

Gregory Minissale, interview with the artist, ‘Black is the Beginning’, in The Herald, Karachi, May 1991, pp.149–53.

Virginia Whiles, ‘Karkhana: Revival or Re-Invention?’, in Karkhana, exhibition catalogue, Green Cardamom, London 2005, pp.26–33.

Virginia Whiles, ‘Deconstructing Miniature’, in Beyond the Page, exhibition catalogue, Asia House and Green Cardamom, London and Manchester Art Galleries and Shisha, Manchester 2006, pp.54–5.

Nazish Ata-Ullah, ‘Conflicts and Resolutions in the Narrative’, in Hanging Fire, exhibition catalogue, Asia Society, New York 2009, pp.51–7.

Nada Raza

March 2014

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

You might like

-

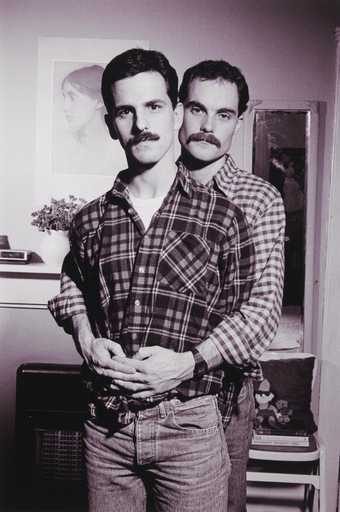

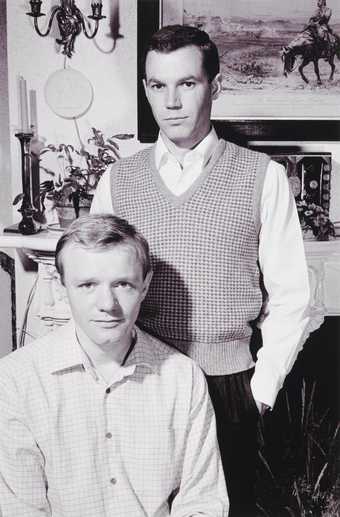

Sunil Gupta Johnathan & Kim, London

1985, printed 2018 -

Sunil Gupta Karl & Daniel, London

1985, printed 2018 -

Sir Anish Kapoor CBE RA Untitled

1989 -

Rasheed Araeen Bismullah

1988 -

Saleem Arif Quadri Landscape of Longing

1997–9 -

Zahoor ul Akhlaq Untitled

1992–3 -

Zahoor ul Akhlaq Untitled

1992–3 -

Zahoor ul Akhlaq Untitled

1992–3 -

Zahoor ul Akhlaq Untitled

1992–3 -

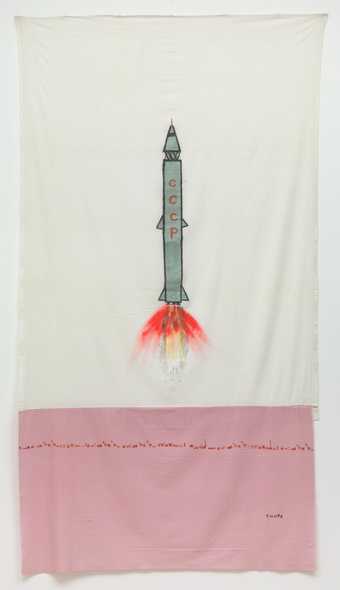

Timur Novikov A Rocket

mid–1980s -

Timur Novikov A Moon-Buggy

1989 -

Salman Toor 9PM, the News

2015 -

Lala Rukh Rupak

2016 -

Mohan Samant Midnight Fishing Party

1978 -

Raqib Shaw Self Portrait in the Studio at Peckham (After Steenwyck the Younger) II

2014–15