Not on display

- Artist

- Craigie Aitchison 1926–2009

- Medium

- Oil paint on canvas

- Dimensions

- Support: 2147 × 1830 mm

- Collection

- Tate

- Acquisition

- Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1987

- Reference

- T04942

Display caption

Aitchison has been painting the subject of the Crucifixion all his professional life. His first one man show in 1958 contained a small painting of the crucified Christ attended by two angels, with a landscape background divided, as here, into coloured bands. Aitchison takes the subject of the Crucifixion, already loaded with associations, ideas and meanings, and recharges it with his own deep and intense emotions by means of shape and colour. Sometimes the figure of Christ has arms but usually he is armless, as in this picture. Aitchison has said 'Everybody knows who he is. He doesn't need arms'. The Crucifixion is set against a hill called Goat Fell, on the Isle of Arran, a childhood holiday place.

Gallery label, September 2004

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

Catalogue entry

T04942 Crucifixion 9 1987

Oil on canvas 2147 × 1830 (84 1/2 × 72)

Not inscribed

Presented by the Trustees of the Chantrey Bequest 1987

Exh: Craigie Aitchison: Paintings 1982–7, Albemarle Gallery, April–May 1987 (30); Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, May–Aug. 1988 (91, as ‘Crucifixion’, dated 1984–5); Spirit of Lamlash: The Paintings of Craigie Aitchison 1954–1994, Harewood Terrace Gallery, Leeds, Aug.–Oct.1994 (29, as ‘Crucifixion’, dated 1986–7, repr. in col.)

Lit:

Helen Lessore, A Partial Testament: Essays on Some Moderns in the Great Tradition, 1986, pp.23–7; Mary Sara in Spirit of Lamlash: The Paintings of Craigie Aitchison 1954–1994, exh. cat., Harewood Terrace Gallery, Leeds 1994, [p.6], repr. [p.15] in col.; Mary Sara, ‘Colourful Character, Colourful Canvases’, Yorkshire Post, 29 Aug. 1994, p.9, repr. (col.)

This painting depicts the crucified Christ on the cross in a dark landscape. Christ wears a pink loincloth; his arms are not represented. Two black birds with orange beaks sit on the left arm of the cross, while on the other side a standing white dog looks up at the Christ figure. The background is divided into three broad bands of colour: brownish-black for the earth, green for the simply-denoted triangular hill and dark blue for the sky.

The artist has identified the hill as Goat Fell, on the Isle of Arran, which dominated the view from his childhood holiday haunt, Lamlash.

The triangular mass of Goat Fell ... is a leitmotif throughout Aitchison's entire oeuvre and a setting for Crucifixions and pure landscapes ... Even given its autobiographical role as a symbol of childhood happiness, adult aspiration and mourning for the past (his parents' ashes were scattered at Lamlash), it is there primarily because each painting in which it appears demands its presence as a form. This is not to deny its objective reality, but to confirm it as an indelible part of his personal, subjective vocabulary.

(Sara 1994, [p.7])

‘Crucifixion 9’ was painted in the artist's studio in Kennington, South London during the first few months of 1987. It was exhibited at the Albemarle Gallery in April 1987 and was the most recently completed work in the show. Aitchison included eight other paintings with the title ‘Crucifixion’ in that exhibition. They are: ‘Crucifixion 1’, 1982, 10 × 12 in (1); ‘Crucifixion 2’, 1982, 16 × 20 in (2); ‘Crucifixion 3’, 1984–5, 68 × 57 in (6); ‘Crucifixion 4’, 1986, 12 × 10 in (9); ‘Crucifixion 5’, 1986, 8 × 6 in (10); ‘Crucifixion 6’, 1986, 7 × 5 in (11); ‘Crucifixion 7’, 1986, 8 × 6 in (28); ‘Crucifixion 8’, 1985–6, 87 × 74 in (29). Of these, only ‘Crucifixion 3’ was reproduced (Craigie Aitchison: Recent Paintings, exh. cat., Albemarle Gallery 1989, [p.11] in col.).

Craigie Aitchison has been painting the subject of the Crucifixion all his professional life. His first one-man exhibition was at the Beaux Arts Gallery, London in January 1959. Catalogue no.1 in this exhibition was a small painting entitled ‘Crucifixion’, c. 1958 (repr. Craigie Aitchison: Paintings 1953–1981, exh. cat., AC 1981, front cover in col.). Christ, a slim figure in a pink loincloth and with reddish hair, hangs on a cross set at the very front of the picture space. An angel hovers at each end of the horizontal bar of the cross. As with T04942, the background is divided into three coloured bands. The lower two are painted in earth colours with hints of blue and can be read as landscape, while the uppermost band, the sky, is rendered in gold. The pink colour of the loincloth is taken up in many of the later Crucifixions including T04942.

In Aitchison's second solo exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1960, five out of the thirty works exhibited dealt with subjects related to the crucifixion: ‘Crucifixion’ (1), ‘The Three Crosses’ (11), ‘Crucifixion and Angels’ (14), ‘Crucified’ (15) and ‘Christ on the Cross’ (22). Only the first was reproduced and the black-and-white photograph reveals a painting in which the horizontal and vertical members of the cross touch the edges of the canvas (Craigie Aitchison, exh. cat., Beaux Arts Gallery 1960, [p.2]). As is the case with the 1958 Crucifixion described above, Christ is presented frontally, in a small loincloth with long hair and his head sagging to the right. His arms are at a forty-five degree angle to the horizontal bar of the cross and he is attended by three angels. No indication of any landscape setting is given.

In his third one-man exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery held early in 1964, Aitchison exhibited eleven paintings, out of a total of forty-five, which were concerned with the subject of the Crucifixion. Only ‘Crucifixion III’ (38) was reproduced in the catalogue (Craigie Aitchison, exh. cat., Beaux Arts Gallery 1964, [p.3]). Again, Christ is depicted frontally and the vertical arm of his cross abuts the bottom edge of the canvas. His arms are in the same position as the 1960 version and his head sags. He has no attendant figures and there is no indication of a landscape setting.

In 1955 Aitchison won a British Council Italian Government Scholarship which allowed him to visit Italy for the first time. The first-hand experience of Italian Gothic and Renaissance paintings still in situ in the churches that commissioned them was a revelation to him. He was particularly impressed by the work of Piero della Francesca and Domenico Veneziano. Aitchison's paintings of the Crucifixion between 1959 and the mid-1960s have a strong flavour of Italian Gothic and Renaissance art, but this influence fell away when Aitchison began to work on a much larger scale in the late 1960s.

His fourth one-man exhibition was held at the Marlborough Gallery in 1968. The show contained eight paintings of the Crucifixion out of a total of twenty-eight works. Although most of these Crucifixion paintings were on a small scale, there were two much larger works, ‘Crucifixion IV’, 1967, measuring 51 1/2 × 38 5/8 in (repr. Craigie Aitchison: Paintings Selected by John McEwan, exh. cat., kettle's Yard Gallery, Cambridge 1979, [p.7] in col.) and ‘Crucifixion V’, 1967–8 (57 × 68 in). In these works, Aitchison abandoned the device of setting the crucified Christ at the very front of the picture plane. ‘Crucifixion IV’ depicts two ranges of hills set against a darkened sky, with a tree in blossom to the left near the foreground and to the right a luminous sheep resting on the slope of the nearest hill. A central band of a lighter tone separates the first range of hills from the second, and Christ on his cross is relegated to this middle ground. Greater prominence is given to the landscape than to the subject matter of the Crucifixion. The larger scale of this work and the formal presentation of the subject anticipate features of T04942.

Between 1951 and its closure in 1965, the Beaux Arts Gallery was run by the painter Helen Lessore. She was responsible for the discovery and promotion of Aitchison's work in the early stages of his career. In the chapter devoted to Craigie Aitchison in her book, A Partial Testament: Essays on Some Moderns in the Great Tradition, 1986, Lessore discusses his choice of subject matter and in particular the Crucifixion (pp.25–6):

These Crucifixions are a very important part of Aitchison's work. They have provoked a great deal of comment and curiosity, and also some attacks. Art, however, should be judged as art - and that includes the whole question of genuineness and depth of feeling; but to consider and examine it as if it were a detailed confession of faith is unsubtle. There is no doubt that Aitchison's religious feelings are genuine and profound, however far they may be from an orthodox belief, and seeing so many Gothic and Renaissance religious pictures in Italy, often still in the very churches for which they were done, made him realise that a whole world of feelings, with which hitherto he had not known how to deal, could be chanelled into these subjects, above all that of the Crucifixion. This image, already loaded with associations, ideas, and meanings, could be recharged with his own deep and intense emotions, by means of shapes and colours - his natural language for everything - in a way for which no other subject provided the opportunity.

He has always done the figure of Christ from imagination, which, inevitably, means drawing from his whole store of memories, however unconscious and unspecific; and these echoes are bound to affect the spectator, whether through the always comforting authority of tradition, or by provoking a comparison, and often a reaction against the new treatment.

... It is a peculiarity of his approach that, while shape and colour are of the utmost importance to him, substance is of none whatever. Simplicity and clearness are, however, vital. So his figures of Christ are unbroken by any marks. Yet they do not have the effect of silhouettes, for they are three-dimensionally conceived, and we feel how the brush made the form, with the slightest possible gradations, working outwards from the central axes of movement, and the dark element in which the figures hang comes up to them, meets and surrounds them, without any contour being drawn. And even though in a few cases the sense of the strained skeleton is more fully realised than usual, we always feel that the figure is of the same substance throughout - that we could pass a sword through it and no blood would flow, it would close up again unharmed, like a flame or a sunbeam, composed of luminous particles cohering in some kind of dance.

... This certainly contributes to the timeless, non-historical quality of the Crucifixions. They are both symbol and reality, in an eternal present.

The frequent use of the Tulliallan (for long Aitchison's home in Scotland) or the country nearby, as a setting for them, is as natural to him as it was for the old Italian painters to use their local landscape.

In T04942, the figure of Christ is armless and this is a significant feature of Aitchison's Crucifixion paintings. As early as 1959, in the painting ‘Crucifixion’ (Arts Council, 50 × 40 in), he had depicted the crucified Christ without arms. In an interview with art critic Andrew Lambirth, published in the catalogue for his solo exhibition at the Albemarle Gallery in 1989, Aitchison discussed the fragmentary nature of his figures (Albemarle Gallery exh. cat., 1989, [p.5]):

Why do you leave out so much?

Sometimes I think I don't leave out enough. I don't consciously leave out anything. The Crucifixions always start off anatomically correct with everything in; then later on I might take things out.

In T04942 Christ is attended by a dog who displays reticent yet tender concern. Aitchison often paints dogs in his Crucifixions and other paintings, and is the current owner of two Bedlington terriers, Candy and her daughter Dusty. He was interviewed about his love for Bedlington terriers for the Telegraph in 1989 (Sally Richardson, ‘Animal Passions: Craigie Aitchison's Bedlington Terriers’, Telegraph Weekend Magazine, 18 November 1989, p.106). In this interview the artist explained that he acquired his first Bedlington terrier twenty-five years before as the result of seeing the breed pictured in a magazine. ‘They say it's the dog with the appearance of a lamb and the heart of a lion ... I like the shape of them’. In the article he confirmed that he is inseparable from his dogs and that they are an inspiration to him and have appeared in his paintings since 1974. When Wayney, his last male Bedlington terrier, died in 1986, Aitchison painted a picture entitled ‘Wayney Going to Heaven’ which depicted the dog suspended upside down between heaven and earth. ‘After Wayney died I had about four months when I couldn't do the pictures. I didn't know what I was doing. I don't usually paint as emotionally as I did with this, so when people liked it I was amazed. I thought it was too personal’ (ibid.). When questioned by Lambirth about his use of animals in the Crucifixion paintings, Aitchison replied: ‘The animals are meant to be upset, concerned. It's as though the animal is walking along and is suddenly amazed and horrified and looks up. But there are Crucifixions I've done where the animal is sitting at the foot of the cross completely resigned.’ (Albemarle Gallery exh. cat., 1989, [p.5].)

In the passage cited above, Helen Lessore referred to the depth of Aitchison's religious beliefs. Aitchison's grandfather was a Scottish Presbyterian minister and his father allowed his son to experience a great variety of forms of worship as a young man, including Roman Catholicism. Its more splendid rituals especially appealed to the artist. Aitchison has discussed the influence of his family background on his work (Albemarle Gallery exh. cat., 1989, [p.5]):

You have something of a religious background...

Do you think this has any bearing on why you paint Crucifixions?

No, I don't, but of course it could have.

Have you ever used a model for Christ in the Crucifixions?

No.

Are your Crucifixions always set against the Scottish landscape of your childhood?

It seems they are, but it's not intentional. In fact, there are two recent yellow ones which don't have the hills in them. And the early Crucifixions don't have any hills in them. I put the mountain in when I wanted the figure to be in a special place.

When Aitchison was a school boy in Scotland, he became attracted to the world of art by reproductions of Van Gogh and Gauguin bought by his father. He also remembers the impact of first seeing Salvador Dali's ‘Christ of St John of the Cross’, 1951, in Glasgow (Glasgow Art Gallery, repr. Paul Moorhouse, Dali, 1990, p.101 in col.): ‘There was a huge row when I was at school because the Glasgow Corporation bought it with what people thought was too much public money. I remember going to see it and being absolutely amazed the way the cross completely went into the canvas, like an illusion. I still like that picture’ (ibid., [p.3]).

No preparatory drawings would have preceded the painting of T04942 since Aitchison does not work from studies. Lambirth (ibid., [pp.4–5]) asked the artist about his working method:

Do you make preparatory drawings for a picture?

No, never.

Do you draw on the canvas?

If you mean with a pencil, I used to do that. I paint from the inside out, so if I'm painting an arm I itch the paint from the inside to the edge to get a line. When I was at the Slade I used not to know how to do that. I was frightened to use the paint, so I used a pencil to draw the profile on the canvas. But the pencil line spoilt it, I'm not a line person. I had to evolve the method of itching it to the edge and finally drawing the edge with a small knife.

... You are known for painting very thinly. Why do you paint this way?

It's the only way I can. It's also much easier to alter the paint when it's thin and all I do is alter it. Once or twice I did try with thick paint, I thought I had only to put more paint on and I could get it right, but then that was no good because there was no tension left; the surface of the canvas had gone and when I lose that, everything has gone.

The artist has approved this entry.

Published in:

Tate Gallery: Illustrated Catalogue of Acquisitions 1986-88, London 1996

Explore

- places(26,467)

-

- UK counties(19,585)

- UK countries and regions(24,355)

-

- Scotland(2,977)

- UK natural features(5,430)

-

- Goat Fell(2)

- Isle of Arran(9)

- Bible: New Testament(545)

-

- Christ(281)

- Crucifixion(84)

You might like

-

Peter Doig Untitled (Ping Pong)

2006–8 -

Peter Doig Canoe Lake

1997 -

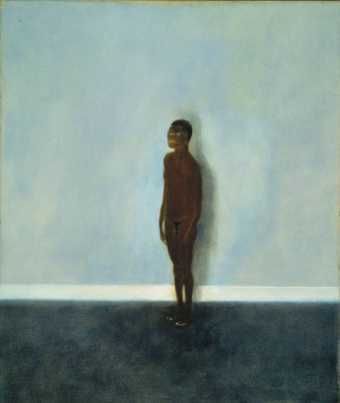

Craigie Aitchison Model Standing against Blue Wall

1962 -

Michael Moon Drawing

1976 -

Michael Moon Table

1978 -

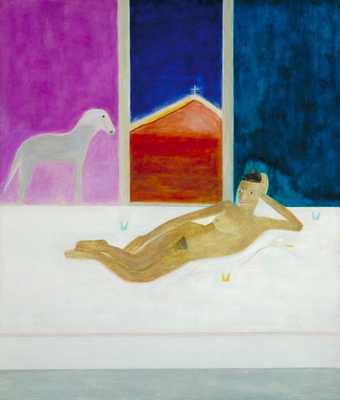

Craigie Aitchison Model and Dog

1974–5 -

Peter Doig Ski Jacket

1994 -

Callum Innes Three Identified Forms 1993

1993 -

Peter Davies Small Touching Squares Painting

1998 -

Peter Doig Echo Lake

1998 -

Carol Rhodes Ridge

1999 -

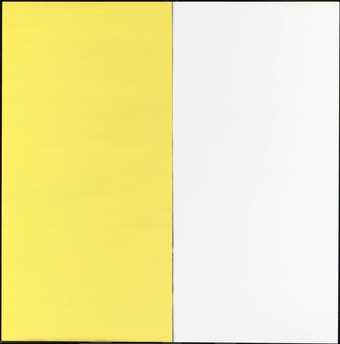

Callum Innes Exposed Painting Paynes Grey/Yellow Oxide/Red Oxide on White

1999 -

Carol Rhodes Airport

1995 -

Callum Innes Untitled No 39

2010 -

Callum Innes Untitled No 51

2011